Marco Rubio’s presidential campaign is running into an unusual problem without precedent in the post-Reagan era: His tax cut is too big. The trouble is not so much that his tax cut is substantively too big — within the context of a Republican primary, a “too-large tax cut” does not even make linguistic sense; it would be like saying “Reagan is un-good.” Rubio’s slightly different problem is that his tax cut is so gargantuan that nobody in the party actually believes it.

The context for Rubio’s plan is a debate within the Republican Party over the party’s agenda. For more than 25 years, the party has been organized around the central goal of reducing taxes paid by the rich. In recent years, a small group of conservative intellectuals have questioned that goal, both on substantive grounds (lower taxes for the rich have less economic payoff today than they did when the top tax rate was 70 percent) and on political grounds (the GOP’s attachment to cutting taxes for the rich has become a major political liability).

Those dissidents, called reform conservatives, or reformicons, or reformocons, have broached the subject gingerly. They are playing an inside game, trying to work their way into the party’s inner circle without offending the existing power structure. Their plans have mostly taken the form of suggesting that Republicans add tax credits for middle-class families to their traditional plans to cut taxes for the rich.

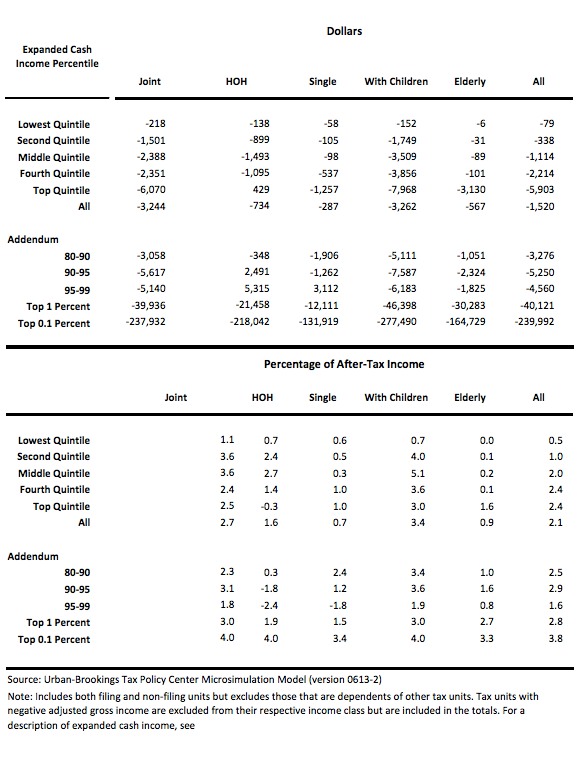

Faced with a debate between a faction that really wants to cut taxes for the rich and a faction that really wants to cut taxes for middle-class families, an obvious solution beckons: do both! Rubio’s first stab at pleasing both factions came last year, when he proposed what he called a “tax reform,” but which turned out upon inspection to be a traditional tax cut. In its basic design, Rubio’s original proposal was basically a replay of George W. Bush’s tax cut. It would have drained about two and a half trillion dollars from the Treasury over a decade (roughly similar to Bush’s tax cut) and with a somewhat regressive tilt to the payout. The lowest-earning fifth of taxpayers would have saved, on average, $79 a year, or 0.5 percent of their income. Taxpayers in the middle fifth would have saved about $1,100 a year, or 2 percent of their income. And the highest earning one percent would have saved $40,000 a year, or 2.8 percent of their income. Here are the figures, courtesy of the Tax Policy Center:

The telling thing is what happened next. Rubio got some feedback from Republicans and decided that his plan was flawed. Specifically, its major flaw was that it did not cut taxes for the rich nearly enough. The measly $40,000 a year the average one percenter would save hardly moves the needle in a party where candidates are turning to the likes of Stephen Moore and Arthur Laffer to outbid each other to relieve the affluent of their tax burdens.

So version two of Rubio’s plan added on some new features. Rubio now promises to keep all his previous tax cuts, plus he would eliminate all taxes on capital gains, dividends, interest, and inherited estates. This isn’t “buy a new BMW every year” type money for the one percent. It’s more “Scrooge McDuck swan dive into a pile of gold” type money. Paris Hilton’s descendents would be able to go several generations deep into the future without anybody working a day in their life.

But that’s not all! When asked by the Tax Policy Center, Rubio’s staffers also promised they would make their tax-cut plan refundable to low-income earners. These two additional measures, in combination, would add trillions more to the revenue loss. (I am using general descriptions here, because the new Rubio plan is too incoherent to be measured.) Given that Rubio also favors significant increases in the defense budget, no cuts to retirement programs for anybody over the age of 55 (thus walling off those programs from any savings for a decade), and, oh yes, a Constitutional amendment to require a balanced budget every year — well, let’s just say there is reason to doubt the viability of his fiscal promises.

The reform conservatives greeted Rubio’s plan with tepid, carefully tailored praise. “While Rubio’s plan loses too much money, and taking investment tax rates all the way to zero would seem a political bridge too far, these are fixable issues, and something like the Rubio plan might pass some future Congress,” wrote reform conservative James Pethokoukis, optimistically.

The supply-siders have offered more biting assessments. “With this proposal, Senator Rubio makes himself the party’s most visible ally of the ‘new’ Republican idea that the Reagan tax-cutting agenda is a political dead end, and that the party now must redistribute revenue directly to middle-class families,” concluded The Wall Street Journal editorial page. This is a rather ungenerous assessment, given that Rubio’s plan would cut the top tax rate lower (to 35 percent) than George W. Bush’s tax cuts did (36 percent), not to mention eliminate taxation on all wealth-based income, which Bush’s tax cuts merely lowered. The Journal’s oddly cool response is explained by a comment by Moore, a former Journal writer, die-hard supply-sider, and current Republican adviser, who tells Al Hunt, “The problem is the more you increase things like the child tax credit, the more you will move back to the 1960s and ‘70s tax system with higher tax rates. Instead, we need much lower rates and a broader base.”

In other words, increasing the child tax credit costs money. The supply-siders are afraid that Rubio’s plan to cut taxes for the middle class would cost too much, forcing him to “fix” his plan by curtailing his promises to rich people. The reform conservatives are aggravated and befuddled that the supply-siders refuse to meet them halfway, or even a quarter of the way:

But the supply-side reaction is perfectly rational. Rubio’s plan is so wildly grandiose and unrealistic that even so math-challenged a figure as Steve Moore realizes it won’t add up. One of the things you learn growing up is that winning a bet for a dollar is worth more than winning a bet for a million dollars, because no kid ever pays up a million-dollar bet. Rubio’s plan is so crazy and unrealistic it might as well be no plan at all.