Republicans, and observers of the Republican Party, have concluded that Donald Trump’s gonzo commandeering of their presidential primary has defied their attempts to suppress it because he is crazy. This is broadly true, but not quite in the way Trump’s befuddled critics mean it. What they say is that Trump is winning because he attracts voters with nonsensical ideas. Lindsey Graham calls Trump “a huckster billionaire whose political ideas are gibberish.” Former New Mexico governor Gary Johnson tells Evan Osnos, in Osnos’s paraphrasing, “anyone who runs for office discovers that some portion of the electorate is available to be enraged and manipulated, if a candidate is willing to do it.”

Trump has certainly crafted an appeal to voters who like impractical ideas. But his true threat lies in the fact that Trump himself is crazy — not just ideologically, though he is certainly that as well, but in the sense that he lacks any rational connection between his actions and his goals, to the extent that his goals are discernible at all. That is also his downfall.

For a long time, the political profession believed that Trump would never run for president. A profile by McKay Coppins last year framed Trump’s long history of teasing reporters with campaigns that he would not undertake as an unbreakable pattern of publicity-hounding. “Over the course of 25 years, he’s repeatedly toyed with the idea of running for president and now, maybe, governor of New York,” explained the story’s summary. “With all but his closest apostles finally tired of the charade, even the Donald himself has to ask, what’s the point?”

Trump defied the skeptics by actually announcing a run for office. He then defied the skeptics by surging into the polling lead, and again by maintaining his lead in the face of a withering assault by the Republican Establishment, led by Fox News.

By design or (more likely) by accident, Trump has inhabited a ripe ideological niche. Both parties contain ranges of opinions within them. And both are run by elites who have more socially liberal and economically conservative views than their own voters. (There are plenty of anti-abortion, anti-immigration, anti-same-sex-marriage Democrats not represented by their leaders.) But the tension between base and elite runs deeper in the Republican Party. Conservative leaders tend to care very little about conservative social policy, or even disagree with it altogether. Conservatives care a great deal about cutting the top tax rate, deregulating the financial industry, and, ideally, reducing spending on social insurance — proposals that have virtually no authentic following among the rank and file.

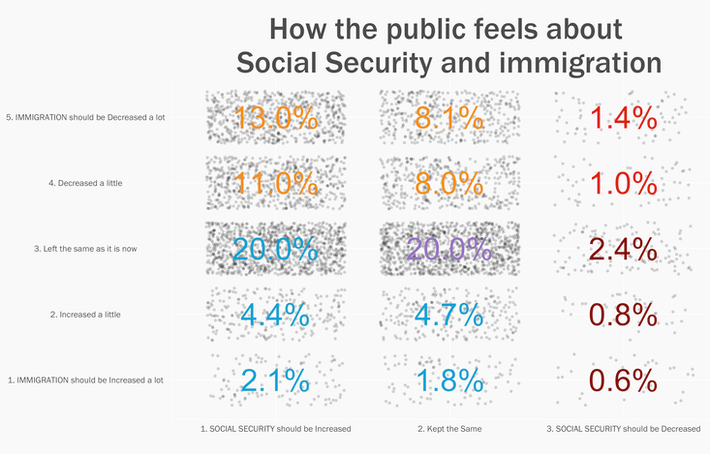

This chart by Lee Drutman, tracking public opinion on immigration and Social Security, displays the disconnect:

The sparsely filled bottom right corner represents the libertarian-ish leanings of the Republican elite, which would like to liberalize immigration law and decrease Social Security benefits. The upper left corner, thick with dots, represents the populist, opposite combination: higher Social Security spending and less immigration. The Republican field — all of which, other than Trump, has endorsed raising the Social Security retirement age — is fighting over the tiny right side, leaving the huge upper left all to Trump. A new poll shows Trump leading New Hampshire with 35 percent, and the next-highest candidate, John Kasich, pulling in 11 percent. A South Carolina poll has Trump pulling in 30 percent of the vote.

Trump has homed in on a bona fide weakness in the Republican Party structure, one that has fascinated liberal critics in particular. The Republican Party has harnessed one set of passions, and then channeled them into unrelated policy outcomes favored by the party elite. Historically, the passions they have harnessed have revolved around foreign policy — like anti-communism, or the surge in nationalism following 9/11. Some of those passions have revolved around culture — a love of guns, the Pledge of Allegiance, a disdain for politicians who look kind of French, and so on.

But the classic formula seems to be yielding diminishing returns. Since 2012, the Republican Party has been attempting to work out a social profile that is better suited to an electorate in which blue-collar whites account for a declining share of the vote. Party strategists believe that the GOP’s long-term interests, and probably its short-term interests as well, require it to heal its disastrous standing among Latinos, Asian-Americans, and white voters with a college degree. They have no consensus over just how to handle it. The three major contenders differ in their approaches. Jeb Bush is trying to maintain his mainstream credibility throughout the primary, keeping the door open for endorsing comprehensive immigration reform. Scott Walker is running as a traditional, down-the-line conservative. Marco Rubio is carving a space between those two.

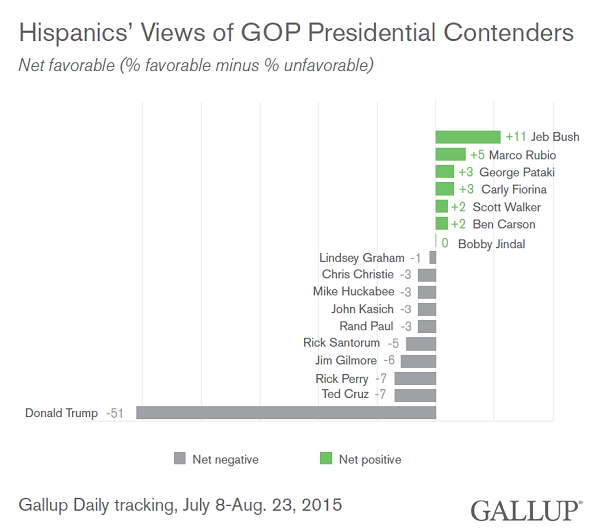

Trump offers no plausible solution to this conundrum. Everything about his persona seems designed to worsen it. His populist style appeals to some blue-collar whites, but is poison among the college-educated voters who have defected from the Republican coalition since the 1990s. His grotesque misogyny would deepen the hostility of women. And Trump has made himself the symbol of anti-Latino racism. His standing among Hispanic voters is off-the-charts bad:

There is little reason to conclude that the reaction to Trump’s characterization of immigrants from Mexico as rapists and murderers has humbled him. He has embraced the most nativist elements of the restrictionist movement. Last night, when Jorge Ramos — often called the Walter Cronkite of Hispanic America — tried to ask a question, Trump berated him and barked, “Go back to Univision.”

So the prospect of a Trump nomination justifiably terrifies Republicans. But unlike the prospect of nominating a Scott Walker — or a more extreme version, like Ted Cruz — the risk does not carry any proportionate reward. Bush, Walker, and Rubio all agree on the same basic domestic goals. If elected, they will try to enact the party’s agenda on taxes, regulation, and social spending.

Trump dissents from the field not just in his political strategy but in his overall orientation. While he shares the Republicans’ disdain for President Obama, he has not committed himself to a Republican program. Jeb Bush has frantically tried to question his commitment to the party by pointing out Trump’s prior support for single-payer health care and a large tax on the wealthy. These positions horrify the Republican Establishment. (A recent Wall Street Journal editorial cites Trump’s ability to defy the opinions of the donor class as a major reason to oppose him.) But few Republican voters find them actually disqualifying. The danger he poses is the prospect of harnessing the social passions of the conservative base and channeling them into (from the party’s point of view) the wrong agenda.

Trump poses a dire threat to the party: If elected, he could not be trusted to work for the Republican agenda. The party elite will oppose Trump with everything it has.

Trump has responded to attacks from fellow Republicans the way he has always conducted his feuds with journalists, celebrities, reality-show victims, or business rivals. The crude put-down (with misogynist overtones if his target is female) is Trump’s signature métier. And so he has insulted influential party actors like George Will, Charles Krauthammer, Megyn Kelly, Karl Rove, Michelle Malkin, Dick Cheney, the last three Republican presidential nominees, and so on. He negotiated a peace with Fox News, the party’s quasi-official propaganda organ, and then blew it up for no reason.

In the short run, this can work. Trump is a polarizer. His grotesque, bombastic arrogance has worked very well as a business strategy. Everybody has an opinion about Trump, positive or negative. From a commercial standpoint, it doesn’t matter much which is which. Trump-haters will tune in to his show just as Trump-lovers will. Even if three-quarters of the public wants nothing to do with him, the quarter that admires Trump forms a massive customer base. That is how he has built a lucrative brand for golf courses, hotels, restaurants, beauty pageants, and so on.

But politics does not work like business. You can get rich being loved by a quarter of the country and hated by the rest, but you can’t get elected president that way. Trump has a brilliant strategy for winning the loyalty of a quarter of the primary electorate, or perhaps a third. He has no strategy for winning a majority, which is what you need to get the nomination. Indeed, the things Trump has done to elevate his profile have pushed that majority further from his reach. If the campaign gets to the point where there is one candidate left standing against Trump, that candidate will enjoy the unified support of the party’s financial, media, and organizational strength. Trump has the power to destroy, but not to conquer.

Which brings us back to the question of what it is Trump is after. His presidential campaign seems to have come at enormous financial cost. His undisguised (or less-disguised) racism has made him an economic pariah. He has lost sponsorship agreements from a long list of corporations that want to sell things to people who aren’t white. He’s traded his lucrative brand for Pat Buchanan’s brand.

This immunity from consequence gives Trump the power to wreak apparently limitless havoc upon what is currently his party. The consequences Republicans impose for Trump’s offenses have no effect on him. You cannot threaten a man if you don’t even know what he cares about. Is Trump running to spite the reporters who mocked him as a bluffer? As an expensive lark, like the time he got piano lessons from Elton John? To use his political fame to trade up for his next wife? Does Trump actually believe he can become president of the United States?