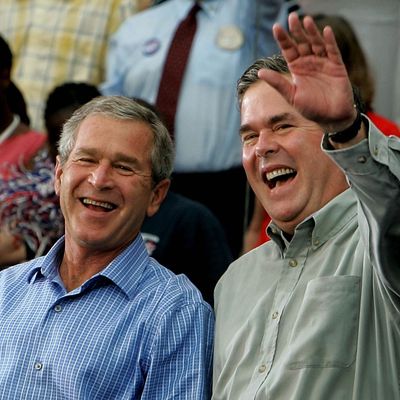

Like all of the non-Trump Republican candidates, Jeb Bush’s economic strategy is built around a program of regressive, debt-financed tax cuts, just as it was under the last Republican administration. In a very clever interview, John Harwood repeatedly asks Bush why he is pursuing this course despite its repeated failure. Bush’s attempts to respond reveal the tangle of denial, non-falsifiability, and cant that undergird the party’s unshakable commitment to voodoo economics.

Harwood begins by pointing out that raising taxes on the rich produced a prosperous economy under Bill Clinton, while cutting them yielded a miserable economy under George W. Bush. Bush replies that the Clinton recovery didn’t have much to do with Clinton’s policies, but it came about as a result of policies undertaken two presidencies earlier:

First of all, I think you have to factor in that policies have long-term impacts. So the tax reform of the 1980s created an environment that President Clinton took advantage of. The PAYGO budget compromise, where there was an increase in taxes, but there was more importantly, a rule that every dollar of additional spending required a cut in spending, was very effective in restraining government during the Clinton era as well.

Presidents and Congress have an impact particularly on tax policy to shape economic growth or the lack of it. The results can occur for a short period of time or a long period of time. The tech bubble created enormous economic activity. You think about all the capital gains revenue that came when people were selling stocks, and so then the crash created the opposite effect.

Okay, so the Clinton-era boom wasn’t because of Clinton. It was because of Reagan and the tech bubble. Now, keep that in mind when you listen to Bush explain the economic results under the next two presidents. Here is Bush putting a positive sheen on the Bush-era economy:

Well, look, he was impacted by some big secular events. The tech bubble, 9/11 — those had huge impacts. And— and so you— it’s hard to tell what— what part of the economy policy drove economic— ‘cause there was— there was growth in the middle of his— of his tenure, after the rec— after the recession …

Notice that the tech bubble counts here as a reason to discount growth under Clinton and to excuse the lack of growth under Bush. But the Bush-era housing bubble under Bush does not discount growth under Bush. Instead, he lamely suggests that, after the recession that began in Bush’s first year, and before the recession that began in Bush’s last year, the economy grew in between, if you ignore the gigantic bubble that drove that growth. Let’s try that plan again!

These arguments are especially rich when you consider Bush’s argument against the Obama-era economic record. That record is hard to evaluate because the current economic cycle has not yet run its course. But Harwood notes that the hysterical doomsaying predictions that Republicans made — that the expiration of the Bush tax cuts for the richest incomes, the implementation of Obamacare, and Dodd-Frank would all destroy the economy — have shown no signs of coming true. (This portion of the interview is not in the abridged online version and comes from Harwood’s full transcript.) Bush replies:

It’s the— well, it’s the worst recovery in modern history. And disposable income for—

Harwood: Well, he had the— he— he— he inherited the greatest recession since the Great Depression.

Bush: Yeah, we’re in year six. At what point do we say, “The dog—” stop saying, “The dog ate my homework,” and it’s someone else’s responsibility?

So Bush has dismissed the entire Clinton economic expansion as the work of the person who held office two presidents before him. And he’s dismissed the entire miserable Bush-era economy as the product of a series of events — tech bubbles! terrorist attacks! — over which he had no control. But the still-going Obama economy is terrible, and any explanation that involves external events, like a worldwide financial collapse, are just poor excuses, and Bush doesn’t want to hear it.

Harwood repeatedly asks Bush why, given his purported interest in inequality, he proposes “a policy that confers a huge proportion of its gains in the immediate sense on people at the top of the income scale.” Bush replies, “On personal rates, in our plan the people at the highest level, 1%, 10%, 20%, the people in the top 20%, pay proportionately more under our plan.” In fact, 53 percent of the benefit of Bush’s tax cuts would accrue to the richest one percent, who earn about 21 percent of the national income.

Harwood also asks, “How does eliminating the estate tax help anybody’s right to rise? That tax only applies to people who have made it big time — they’ve risen.” Bush’s reply is pretty amazing:

Well, they’re dead. If they’ve lived a good life, outside the money they’ve made, they’re up in heaven looking down on us …

What we’ve suggested is that a family asset doesn’t get taken away. When someone does sell the asset — the next generation — they’re paying on the full amount of the appreciation. That’s the compromise position. And that allows for second-generation businesses to continue to flourish. People have earned this through good fortune and a lot of hard work and taking risks. I don’t think you should take that away from families.

… And there is your most honest Bush answer of the interview. Giving a huge tax break to people who have inherited an estate exceeding $10 million (the current tax-free exemption level) has so little to do with the “Right to Rise” that Bush can’t even come up with a rationale. He just explains that he thinks they should be able to keep their entire inheritance tax-free because that is his idea of fairness.