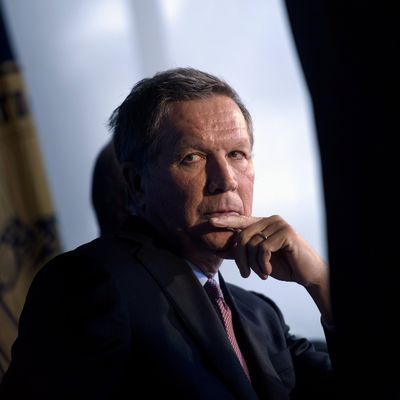

At a recent campaign event, Ohio governor and Republican presidential candidate John Kasich asked rhetorically, “If I tell you that I have a plan to balance the budget, would you believe me?” Apparently, many people do. Kasich, as he has done his entire political career, has cast himself as a voice of fiscal honesty, “the Republican Party’s truth-teller on taxes and spending,” as the Washington Post recently crowned him. “I actually have a plan,” he boasted at the last presidential debate. “I’m the only one on this stage that has a plan that would create jobs, cut taxes, balance the budget.” And Kasich is certainly saying some honest things about his fellow candidates whose “fantasy tax plans” he lambastes. The trouble is that Kasich himself is every bit as much a fantasist as his rivals.

The key element of the Kasich myth is the 1997 Balanced Budget Act, which he credits with producing surpluses in the 1990s. “I balanced the budget in Washington as a chief architect,” he claimed at the last Republican debate, echoing a frequent boast. Kasich’s iteration of his origin story is almost a pure inversion of fiscal reality. Two major laws eliminated the structural deficits of the Reagan era. The first was the 1990 budget deal George Bush struck with congressional Democrats, which cut spending, imposed new rules forcing any new tax cut or social program to be paid for, and increased taxes. Kasich, like most members of his party, voted against it because it raised taxes. That law reduced the deficit by 1.4 percent of gross domestic product over five years. In 1993, President Clinton, working with Democrats in Congress, passed another major deficit-reduction plan. (Clinton’s cuts reduced the deficit by 1.2 percent of GDP over five years.) Kasich voted against that, too, for the same reason, and also predicted that its increase in the top tax rate would “kill jobs” and “[put] the economy in the gutter,” and insisted, “This plan will not work. If it was to work, then I’d have to become a Democrat.”

Instead of the recession Kasich predicted, an economic boom followed, which led to much faster growth and higher revenues than even the Clinton administration had forecast. If the events following the passage of Clinton’s deficit plan did not show that it worked, then no evidence could prove that it worked. Nonetheless, Kasich did not become a Democrat.

In fact, by 1997, the deficit was on course to disappear. Lawmakers in both parties decided to capitalize on the good fortune by passing a budget they could call a “Balanced Budget Act,” thereby taking credit for something that was set to happen without any action. The resulting deal cut Medicare, but split the savings between a new Childrens’ Health Insurance plan, which Democrats liked, and a capital gains tax cut, which Republicans liked. It barely netted out, trimming the deficit by just 0.2 percent of GDP.

Kasich, in other words, opposed the two main laws that created the balanced budget in the 1990s, and supported one that had nothing to do with it. He continues to maintain that he would oppose any tax increase, even a budget deal that combined a 10-1 ratio of spending cuts to tax hikes.

Building upon his almost entirely imagined record as mastermind of the 1990s budget surplus, Kasich touts what he and his press clippings call his “plan” to balance the budget in eight years. In actuality, it is not a plan at all. Kasich has a bunch of numbers for spending, but he does not say what he would do to arrive at those numbers. For instance, he would freeze all domestic discretionary spending, a wide catch-all category of general federal spending on scientific research, infrastructure, law enforcement, and many other things. This spending has absorbed deep cuts for several years — so deep, in fact, that Republicans in Congress have had trouble funding tolerable savings and compromised on a plan to cancel out some of the additional cutting. Kasich proposes to hold spending on this category constant in nominal dollars, which means that, accounting for population growth and inflation, services will have to be reduced every year. Kasich does not specify how he would allocate those service cuts.

Kasich would cap spending on Medicaid, a program that provides health care to the desperately sick and poor (and is far cheaper than private insurance). That is a bona fide program cut that would slash 13 percent off its outlays by the end of the Kasich administration. Kasich would also cut Medicare spending by 10 percent by encouraging widespread adoption of Medicare Advantage (which Kasich believes saves the government money, in spite of the fact that Medicare Advantage costs the government more per beneficiary than traditional Medicare). He would also impose deep cuts on a wide variety of other income security programs — food stamps, deposit insurance, military pensions — but, again, provides zero detail as to which of these programs he would cut, and how much. Kasich simply plucks numbers from broad categories, allowing him to claim large savings without having to defend cuts to any program in particular.

Balancing that off is Kasich’s plan to cut taxes. There is not yet an official score for the cost of Kasich’s plan, a fact that by itself nullifies the campaign’s claim to have a plan to balance the budget. You can’t bring revenues and outlays into line if you have no idea what revenue levels will be. Imagine a business claiming it has a target date for breaking even, and then conceding it has no idea whatsoever what its earnings will be.

By the eyeball test, the scale of the revenue lost by Kasich’s tax cuts will be absolutely massive. Kasich would cut the top tax rate to 28 percent from its current 39.6 percent rate. He would cut the capital gains tax rate from 25 percent to 15 percent, cut the estate tax rate from 40 percent to zero, cut the business tax rate from 35 percent to 25 percent, and allow businesses to immediately write off the full cost of all investments — a tax cut for the rich of a scale never before seen in American history. Kasich would also expand the Earned Income Tax Credit for the working poor, which is nice, though it further raises questions as to where he will find the trillions of dollars in savings to pay for all this. Kasich’s campaign tells me that he believes deep tax cuts will encourage faster growth, undeterred by the clear past failure of his beliefs about tax rates and growth.

In sum, it is inaccurate to say Kasich has a plan to balance the budget. It would be accurate to say that he is promising to eliminate the deficit, but he has a plan to dramatically increase it, at least if you define plan to mean the actual change to taxes and spending that he has specified.

Kasich has gotten the benefit of the doubt because he’s the only candidate who has questioned the feasibility of his rivals’ budget plans. “We hear a lot of promises in this debate, a lot of promises about these tax cuts or tax schemes sometimes that I call them …” he said in the last debate. “We’ve got to be responsible about what we propose on the tax side.” You should trust Kasich when he talks about other candidates, but not when he talks about himself.