First off, the facts as they are known: The Canarsie Tube, the tunnel that carries the L train under the East River from Brooklyn to Manhattan and back, is a mess. Hurricane Sandy more or less filled up the portion of the tunnel under the river, plus a bit on either side, significantly damaging about three miles’ worth of concrete, cables, signals, and rails, plus a pump room near Avenue D. And no, Sandy did not single out the hipsters: Nine such underwater tunnels were damaged during the hurricane, in varying degrees, and three are either under repairs or fixed already. Most of those, like the R train’s Montague Tube, are in areas that were at least somewhat doubly served, mitigating the pain.

The L is next, and for the inner-Brooklyn portion of its run, it’s pretty much the only train around that runs to Manhattan and back. It now carries about 350,000 riders per day, up significantly in recent years (4.7 percent in 2014 alone!) as Williamsburg and Bushwick entered their postindustrial lives. And quite a few of those thousands may have a problem next year, because that tunnel has to be fixed, and the train may come to a halt. All the options available, from shuttle buses to gondolas to some version of the new and enticing light-rail proposal, fall well short of the ability to handle that very large number of people with any kind of efficiency.

The repair contract for the tunnel was bid out with an estimate that it would take 40 months of weekend work. Last year, the excellent subway blogger at Second Avenue Sagas did a nice job of explaining how bad the damage was, and noted one small upside to the rebuild — that the First Avenue stop, in Manhattan, will gain a new entrance at the eastern end of its platform, serving Avenue A.

Most cities do maintenance and repairs at night, when the trains are not running. (The London Underground mostly closes down at midnight.) That is not an ordinary option in the City That Never Sleeps, although night-and-weekend service interruptions have become routine. This time, though, the MTA has floated the possibility of another scheme: Closing the tunnel completely would allow the work to be done in a year rather than three and a half, while (presumably) funneling most Manhattan commuters over to the J/M/Z lines. Certainly, it would make a commuter’s life that much worse, but it would also perhaps lessen the pain in a rip-off-the-Band-Aid-in-one-go kind of way. There is an alternative plan to close one side of the Canarsie tube (which is really two tubes) at a time, and shuttle people back and forth on the single other track as work is done. If you’re a betting person, your money might go there. (The MTA has been mum about which plan it prefers, and did not respond to two requests for comment on this story.)

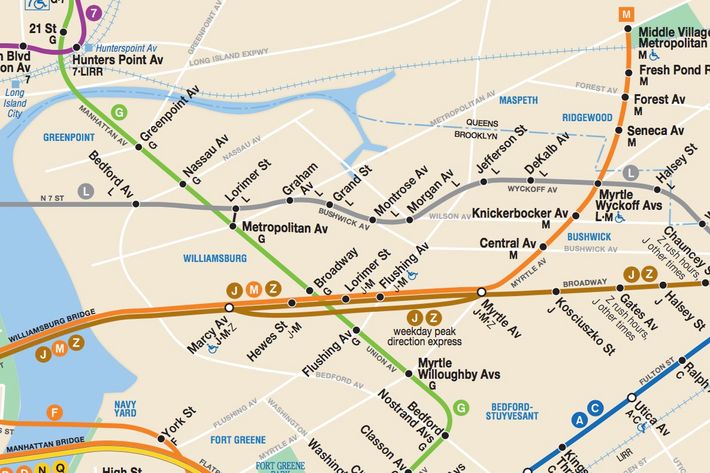

In either scheme, of course, the entire L line would not be closed. Everyone to the east of the Myrtle-Wyckoff stop, coming from East New York and Canarsie, will be able to transfer to the M and, in some cases, the A/C and J/Z, all of which make multiple connections with other lines on their various routes to Manhattan. (This is a rare case where poorer New Yorkers will be somewhat less screwed over than richer ones.) If you’re east of the Lorimer stop, you will be able to transfer to the G train, which is less helpful but at least will take you to another line headed for midtown or downtown. The MTA would be likely to put on extra G service, and it had better, because even that train is not exactly empty right now.

That leaves the people who come through the Bedford Avenue stop, which is the busiest one on the Brooklyn part of the L. Its weekday passenger load in 2014 (the last year for which data are available) was 27,224 people, up more than 50 percent in a decade, and that figure barely dips on the weekends, presumably because of Williamsburg’s social scene. Some of its riders would go one stop over, to Lorimer Street, and catch the G; others would drive or bike or (this being Williamsburg) skateboard. How do you move the remainder to and from their jobs every day? To hear some of them tell it, a full closure would wreck whatever cultural specialness remains in Williamsburg. To which point, a colleague of mine correctly sneered: “Infrastructure doesn’t care.”

Well, let’s work out some numbers. (Stipulated: These figures are speculative.) The ridership statistic above suggests that the trains pick up and disgorge perhaps 5,000 people per hour at Bedford between 8 and 10 a.m. and 5 and 7 p.m. If a percentage of those go to Lorimer Street instead, and others find alternative routes or work from home or whatever, a decent guess is that 3,000 people an hour will need to be shuttled over to the J/M/Z stop at Marcy Avenue.

You can pack 112 people onto the MTA’s big articulated buses, meaning you’d need 26 of them per hour — one every two and a half minutes. Given that it takes a solid couple of minutes to load that many bodies, something like an entire block would have to become a dedicated bus stop, because buses will literally be lining up. Traffic will cause them to arrive in clumps. (Let us not think too hard about the wheelchair lifts, which are both legally and morally necessary but hugely slow down the boarding process.) Bedford Avenue itself might need a dedicated lane. If you live near the Bedford stop, it’s going to be a very noisy, very crowded, highly diesel-scented year. If you’re going to commute this way, you’d better start getting up an hour earlier. And if you’ve ever lived above a subway line that went out during a rainstorm, you will remember the long waits for a ride home.

The other alternatives to this parade of buses are perhaps more charming, certainly more attractive, and barely workable. Ferries? Sure, if you have a beard and a blacksmith shop, the 19th-century aspect of commuting by ship sounds lovely. But the current fast ferries can carry 399 people, and make a couple of round trips an hour. (They’re also mostly full already, at least at rush hour.) Even if the MTA rented a small fleet of comparable boats, and just had them shuttle between Williamsburg and the stop at East 35th Street, that would handle a tiny fraction of the demand, very slowly. And then the 34th Street crosstown bus, running at its customary four or five miles per hour, would soon become its own kind of hellscape.

The Skyway? Come on. Its proposal claims it could somehow move 5,000 passengers an hour in total, with a car emptying and loading every 30 seconds, but that’s a fantasy. In real life, it would carry maybe 12 people in each of those little pods, when it’s not windy, and would grind to a halt every time an old guy takes an extra minute or so to disembark. (The Roosevelt Island tram has transported 30 million people altogether since it was opened in 1976; the L train carries that many every 90 days.) It’s a lovely amenity — an urban garnish, if you will — but it’s hardly a transit system. Plus we don’t have it yet, and getting it built in months rather than years is a pretty fanciful idea, too.

A friend yesterday suggested that a far larger conventional ferry — Staten Island–size — would do the job passably well, and I was surprised to find that the 24-foot minimum depth of the East River would allow such a boat to dock at either end of the commute. It’d be great if we had, say, a retired Staten Island ferryboat in mothballs, waiting for such an occasion — which, in fact, we did, until it sank and was sold off for scrapping a couple of years ago. Another big ferry, one that had served Martha’s Vineyard for decades, was bought by New York for Governors Island in 2007. It turned out to be a useless rust bucket, and it has ended up in the ship graveyard off Staten Island. So we’d have to find one and fit it out, a process that would probably take about as long as the L-train closure would, and should’ve been started yesterday. As daffy-seeming an idea as it is, it ought to be taken seriously. The capacity of the current Staten Island Ferry is about 6,000 people. For Brooklyn, surely the bicyclists would get to take over the car deck.

The short answer is that it’s going to be a long slog of a year. Uber will make a bunch of money. So, perhaps, will rental brokers, as a small but significant percentage of Williamsburgers head elsewhere. Everyone else: Get your VPN ready. And order a new pair of wet-weather walking shoes.