The Investor-State Dispute Settlement Process (ISDS) is among the least sexy phrases in the English language. Any cable news channel that filled its prime-time block with debates over whether or not the Trans-Pacific Partnership’s ISDS safeguards are robust enough to protect against the erosion of nondiscriminatory public-interest regulations would not be long for this Earth. Discussions of international financial law simply can’t compete with Donald Trump’s latest gaffe or the newest chapter in Huma Abedin’s waking nightmare.

But if news consumers saw beneath the dull surface of our system for international investment arbitration, they’d find something far more fascinating than Anthony Weiner’s penis: “a private, global super court that empowers corporations to bend countries to their will.”

That description comes courtesy of Buzzfeed, which has channeled revenues from its cat and corporate propaganda content into an 18-month investigation of ISDS. The first part of that investigation, published Sunday, reveals that white-collar criminals are using their access to the court as a Get Out of Jail Free card. But before we get into the details, we should probably review exactly what the Investor-State Dispute Settlement Process even is.

One of the many disadvantages of being a developing nation known for political instability is that it’s very difficult to convince foreign companies to invest in you. After all, no capitalist wants to sink millions of dollars into developing an oil field only to have it nationalized a couple of years later. So, in the 1950s, the ISDS was proposed as a means for solving that problem: By establishing a system of binding arbitration on a global scale, developing nations would be able to attract corporate investment, even if their legal systems were less than reliable. This would help increase corporate profits and decrease global poverty, speeding humanity’s way toward neoliberal utopia.

The system was written into virtually every major trade agreement over the next several decades. While the precise rules of the arbitration can vary slightly between treaties, the broad outlines of the process are the same. The vast majority of ISDS cases are aired before a tribunal of arbitrators — typically, private lawyers drawn from the same pool of elite litigators that represent corporations in these cases. The investor and the state each get to pick one arbitrator and then arrive at a mutual agreement over the third.

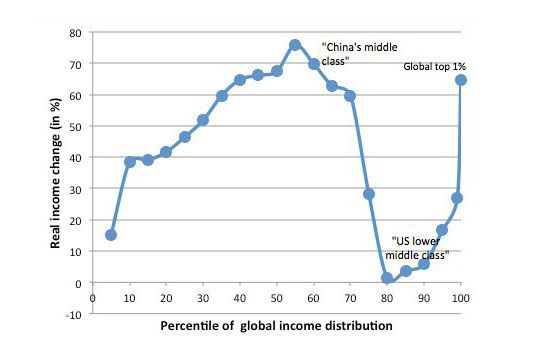

There’s considerable evidence that the global capital flows ISDS helped foster have brought real benefits to the global poor.

But ISDS has delivered even greater benefits to corporate law firms — especially once they figured out how to transform a system designed to protect companies from autocratic thievery into one that protects them from democratic regulation.

Over the past two decades, the frequency of lawsuits against governments in ISDS courts has drastically increased. Buzzfeed’s Chris Hamby illustrates why:

When NAFTA, the North American Free Trade Agreement, took effect in 1994, some lawyers at top firms took notice of ISDS for the first time. One heralded “a new territory” where some pioneering attorneys had ventured and “prepared maps showing a vast continent beyond.” What they saw was the opportunity to expand and reshape ISDS to their benefit, and the previously dormant system changed forever.

A whole industry grew up,” said Muthucumaraswamy Sornarajah, an international lawyer and ISDS arbitrator who argued that the system is now being misused. Large law firms, he said, see ISDS “as a lucrative area of practice, so what happens is they think up new ways of bringing cases before the arbitration tribunals.”

Lawyers’ fees make up the bulk of the roughly $5 million in legal costs that each side pays in an average case, recent studies have found. Big firms can easily bring in significantly more. Top lawyers sometimes bill more than $1,000 an hour. Attorneys billed Turkey more than $25 million in one case, and after Russia lost a mega-case, the country said it paid its lawyers more than $27 million.

These well-compensated lawyers helped corporations repurpose protections against expropriation — government confiscation of private assets for the sake of an ostensible public purpose — as shields against mere acts of disadvantageous regulation. In 2011, Germany was forced to compensate a Swedish energy company after the government imposed strict emissions limits on coal-fired power plants, thus committing an act of “indirect expropriation.”

That term effectively denotes the pursuit of any government policy that massively devalues a private entity’s assets. Defenders of ISDS insist that “indirect expropriation” can be distinguished from routine acts of public-interest regulation. But history and the OECD suggest otherwise.

In addition to the German example, complaints of “indirect expropriation” have been brought against smoking regulations in Australia and Uruguay. Even when states win such cases, the costs imposed by litigating them can stifle regulatory ambition — after Phillip Morris attacked Australia for its tobacco law, the government of New Zealand abandoned a similar initiative.

Buzzfeed News’s exposé focuses on cases in which corporate bigwigs used ISDS not merely to win restitution for regulation, but rather exoneration from criminal convictions.

The most alarming case involves a lead-acid battery factory in El Salvador. Shortly after the factory’s opening in 1998, the rural hamlet of Sitio del Niño starting noticing clouds of ash raining down on their homes and neighborhoods, burning people’s throats and giving children coughing fits. Then large numbers of those children started experiencing extreme fatigue and constant pain in their bones and joints. Years later, testing revealed that dozens of these children had dangerously high levels of lead in their blood.

A court in El Salvador concluded that responsibility for the contamination lay with the factory owners. Per Buzzfeed:

The factory had promised environmental regulators it would upgrade its deficient pollution controls — installing systems to remove lead from the factory’s water, for example, and improving how it stored contaminated slag. But the factory either delayed taking some of these steps for years, the court found, or never actually took them, even though the company’s profit statements showed it had the money to make the fixes. As a result, the court determined, lead seeped into the town’s water supply and blew over from smokestacks and waste piles.

The El Salvadoran government proceeded to order the factory’s closure and bring charges of aggravated environmental pollution against the company, three of its owners, and three lower-level employees.

The company responded by bringing an ISDS case against El Salvador for having “expropriated” the factory, demanding $70 million in restitution. The lawyer who crafted the company’s legal defense, Arturo Girón, told Buzzfeed that the case was brought so as to intimidate El Salvador into dropping its criminal charges.

The company ultimately reached a settlement with the government, agreeing to pay for a limited cleanup — but only at the site of the factory itself — to establish a medical clinic in the village that will only be funded for three years, and to drop the ISDS case against El Salvador. The lower-level managers were acquitted of all wrongdoing. According to Girón, the judges were persuaded to acquit, in part, by “the ISDS threat and its potential to slam the government with huge compensatory damages.”

The government has estimated that it would cost $4 billion to remove the accumulated lead from Sitio del Niño. Children in the hamlet continue to develop severe lead poisoning. Prosecutors have filed new criminal charges against the factory’s owners, but a factory lawyer suggested to Buzzfeed that should El Salvador seek the owners’ extradition, they would be inviting a new ISDS case against their government.

Buzzfeed’s piece details similar instances of alleged white-collar criminals using ISDS as a means of escaping legal liability in Egypt and Indonesia. Their exposé is worth reading in full, because, in the next few months, Congress will decide whether or not to commit the United States to a trade agreement that will drastically expand ISDS’s reach.

According to consumer-rights advocacy group Public Citizen, the Trans-Pacific Partnership will double U.S. exposure to ISDS, as more than 1,000 corporations in TPP counties will gain the legal right to sue America for “indirect expropriation.” The Obama administration claims that the agreement will actually “modernize and reform” ISDS, guaranteeing participating nations’ the right to regulate in the public interest, while making the arbitration process more open and transparent.

Public Citizen’s analysis disputes that characterization, arguing that the TPP’s safeguards are replications of those in previous deals, like the Central American Free Trade Agreement, which have proven to be ineffective. Further, the group charges that the agreement presents novel threats to self-regulation by allowing banks to challenge financial regulations “as violating investors’ ‘expectations’ of how they should be treated.”

For their part, white-shoe lawyers who make a killing off ISDS do not seem to be intimidated by the TPP’s reforms. Rather, those who spoke to Buzzfeed said they see promising loopholes and “are already advising clients how they might use the new deal to their benefit.”

Perhaps the proposed reforms are more robust than these lawyers and hectoring Naderites would have you believe. But the fact that the TPP’s champions so often choose to frame the debate in abstract ideological terms — rather than by defending the substance of the agreement’s most controversial provisions — does not inspire confidence in the strength of their case.

The TPP is about more than just lowering tariffs; it’s also about limiting free trade in pharmaceuticals by extending American drugmakers’ patent monopolies, and expanding the reach of a private super court that appears to be undermining the very concept of national sovereignty. You don’t have to be a “white nativist” to be concerned by such policies.

If the Obama administration wants to convince Democratic voters to support its agreement, it should stop insinuating that its critics are Luddite protectionists and debate them on the merits of their complaints.