Charter schools have existed for just 25 years, and their quality varies. On the whole, charters are more effective in urban areas than are traditional neighborhood schools, but only about equally effective elsewhere. Some states do a great job of monitoring their charter schools (such as promoting good ones and closing down bad ones) while others do a lousy job. One of the best states at charter-school governance is Massachusetts. Unfortunately, Massachusetts has a cap on its charters, denying admission to students who are desperate to attend them. The state legislature, which is heavily influenced by teachers unions, refuses to lift the cap. In November, voters can open up more charter spots by approving a ballot measure.

Charters are public, and unlike private schools, they can’t pick and choose their students. (My wife works for a charter-school network in Washington.) When the number of applicants exceeds available spots, charters hold a lottery to accept applicants. That lottery — while tragic for the children who lose — creates a social-science bonanza: a real-life randomized experiment separating two otherwise identical populations. Columbia* professor Sarah Cohodes and Michigan professor Susan Dynarski studied the performance of urban students who applied for spots in charters, comparing the winners who attended charters against those who lost and had to remain in traditional neighborhood schools.

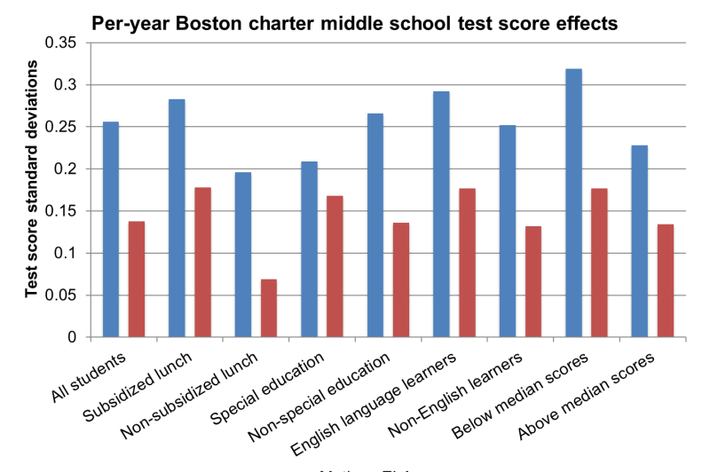

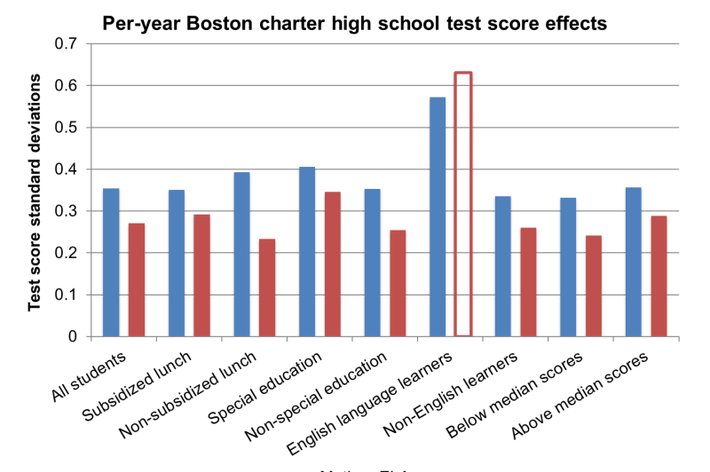

The difference was spectacular. Charter students dramatically outperformed their peers across a wide array of academic metrics:

One frequent response to such results is insisting that charters are merely “teaching to the test.” But that explanation is impossible to square with the superior outcomes of charter students along a wide array of measures, other than high-stakes tests. About twice as many charter lottery winners as losers scored above the median on the SAT, take advanced-placement courses, and scored three or higher on AP tests. Fifty-nine percent of the charter lottery winners went on to attend a four-year college, as opposed to just 41 percent of the charter lottery losers. Cohodes and Dynarski find that the improvement produced by charters is “largest for students who enter charters with the lowest scores,” “urban charters are particularly effective for low-income and non-white students,” and “score gains for special education students and English learners are just as large.”

As the authors note, non-urban charters don’t yield better outcomes. It is only the urban charters that are producing these kinds of improvements. And in the realm of social policy, where producing even small improvements is hard, results like this are revolutionary. A single year of charter-schooling in Massachusetts can wipe out a third of the racial achievement gap, an incredible success. Because urban charters are the ones that outperform traditional neighborhood schools so dramatically, the demand to attend them is naturally high, which is why tens of thousands of urban students are on waiting lists for a chance to transform their prospects for upward advancement.

Massachusetts Democrats, heavily dependent on teachers unions, depressingly, support the cap. Voters can override them at the polls in November. The referendum in Massachusetts is one of the most important tests of social justice and economic mobility of any election in America this fall.

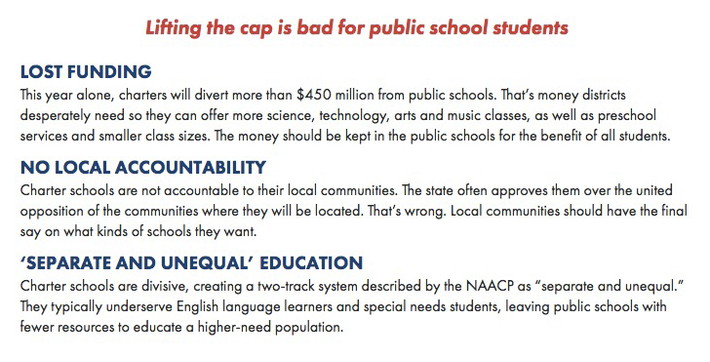

Teachers unions maintain that the cap on urban charters must remain in place, and these children should be forced to attend worse schools. They have three reasons:

The localism argument is correct: Charters are regulated by the state’s excellent, rigorous oversight board, which has closed 17 schools it deemed ineffective or mismanaged. If you believe that schools must be managed by local communities rather than by statewide regulators, you might oppose charters. But a fetish for localism is an odd principle for liberals to espouse.

The “separate but equal” argument is also bizarre. The defining trait of a segregated system is that people are forced into inferior systems and given no choice. It is the unions who want to deny them choice. The cap unions support is what forces urban students to attend inferior schools. Lifting the cap would give more of those students the choice to attend high-performing schools.

The argument that charters will divert funding from traditional neighborhood schools is correct. If more students attend great schools, fewer students will attend mediocre schools, causing a shift of resources from the mediocre schools to the great ones. The question is what matters more: preserving the near-absolute employment security of the tenured workforce at mediocre schools, or giving poor children the best chance at upward mobility?

Update: I identified Cohodes as a Harvard professor. She was at Harvard when she began the research, and is now at Columbia.