For all its recent difficulties, of which there are more below, Obamacare has made American health care both dramatically more affordable and humanitarian. Its various cost reforms have helped bring medical inflation to decades-low levels, and it has given access to basic medical care to 20 million Americans who lacked it before. And yet public opinion has never reflected these realities. The law’s advocates assumed that perception would eventually catch up with reality, but this has not happened, and there is little reason to believe it will anytime soon. And if there is a single overarching flaw in Obamacare, it is a failure to account for politics.

The recent news of higher premiums is a good place to begin to understand Obamacare’s travails. The average premium in Obamacare’s state exchanges next year will be about what the Congressional Budget Office projected when the law was passed. Insurers, having to guess what the brand-new market would look like and eager to scoop up market share, initially set premium levels far below expectations (and, as it turned out, far too low). Now rates are jumping back up to expected levels. The coming reversion to expectations is receiving screaming headlines, while the initial well-below-expectations premiums did not. Why is that?

One reason is that journalists naturally, and in some sense properly, gravitate toward bad news. Holding powerful figures accountable means spotlighting failures and problems in need of correction. But a side effect of this form of covering mostly bad news is a public whose worldview is systematically skewed toward bad news. Broad positive trends are generally invisible — for instance, while violent crime has plummeted over the last two decades, most Americans believe it has risen.

A second reason is the distortions imposed by the partisan imbalance in media coverage of the issue. The conservative media has been engaged in a campaign to discredit and destroy Obamacare, while liberal analysts reporting on the law are both far less numerous and far more restrained by intellectual honesty. News of initially low premiums never broke through in part because conservatives spent the last several years creating a pseudo-narrative in which the opposite was happening. The imbalance between the drumbeat of doomsaying from the right and the caution from the left aggravated the normal bad-news bias.

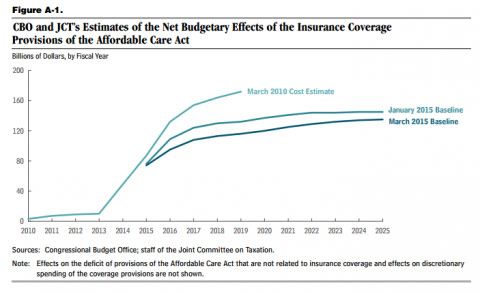

The law’s demonstrable successes are mysteries to the vast majority of the public. A mere 26 percent of the public correctly stated that the uninsured rate has fallen to an all-time low — as opposed to 46 percent who incorrectly believe it is about the same, or 21 percent who, astonishingly, think it has hit an all-time high. A pathetic 5 percent of Americans realize the law has cost the government (which has revised the program’s cost downward numerous times since its enactment) hundreds of billions of dollars less than originally forecast.

This is not merely a problem of optics or political credit. Perception can create its own reality. The exchange markets need enough customers who don’t have dire health needs to enroll in order to maintain a healthy ratio that can maintain affordable premiums. The initial 2017 price correction is not a threat to the system’s viability. The threat is the prospect that the belief that the law is unaffordable drives away customers, creating a cycle of lower enrollment and higher premiums. But the cycle is almost certainly not going to result in a “death spiral” that drives all healthy customers out, for the simple reason that most customers in the exchanges are heavily subsidized. They’ll stay in the market because higher sticker prices will cost them little or nothing.

The good and bad news is that the Obamacare exchanges are not a single market, but 50 individual ones. Some of them are functioning extremely well, which itself demonstrates that the law’s design is perfectly sound. Others are functioning badly. To take one example, states that refused to take federal dollars to cover the law’s Medicaid expansion — that is, states with Republican governors or legislatures who are willing to inflict punishment on their poorest citizens in order to sabotage Obamacare — have more expensive premiums in their exchanges.

The law’s worst-case scenario is not that it falls apart, but that it falls apart in red states whose Republican governors and legislators are committed to its failure. That won’t lead to Obamacare collapsing or being repealed, but to a patchwork system of universal coverage in blue states and a dysfunctional market in red ones. That is not an outcome liberals should cherish — after all, nobody deserves to be deprived of medical care just because Republicans win elections in their state.

But it also means that the law’s architecture will remain in place, and the main questions surrounding it will be when and where Democrats can assemble working majorities to implement fixes. It is completely routine for large social policy reforms to have technical changes afterward. What’s abnormal is the Republican boycott of any measure that might improve the law’s function. Technical fixes to Obamacare are conceptually easy and, given the law’s surprisingly low costs, very affordable.

Political will is another matter altogether. Assembling the necessary elements for an Obamacare patch at the national level will require Democrats to not only hold the presidency, which is very likely, and win back the Senate, which is probable but uncertain, but also win the House, a dire long shot even if the party commands a strong majority of all ballots cast in House elections. The politics look even more daunting at the state level, where legislative districts are also gerrymandered and voter information and turnout is even lower.

Liberals believed that Republican opposition to Obamacare would eventually come at a high political price. As people became accustomed to the benefits of having insurance, they would resist proposals to take them away, just as they resist plans to cut Medicare and Social Security. But the Republicans’ strategy of denouncing the law, sabotaging its function at every turn, and endorsing unspecified alternatives remains about as effective now as it ever has been.