Seven years ago, Kathleen Meese received a mail invitation to a free real-estate course, taught by the faculty of Trump University. It was at the historic theater in downtown Schenectady, a 40-minute drive from her house in upstate New York. The advertising materials claimed Donald Trump could “turn anyone into a successful real estate investor.” Meese, a teacher, was intrigued by the prospect of extra income from flipping houses; her son had Down syndrome and needed ongoing medical care. She decided to go.

A few months later, her savings had been wiped out, and she was in debt that would take years to pay off — with nothing to show for it. “There is no Trump University,” she ultimately concluded.

Meese was one of more than 5,000 former Trump U students who caught a small break on Friday, when the president-elect agreed to settle three lawsuits to pay back part of the tuition his company had collected. The plaintiffs will now have $25 million to divvy up: nowhere close to the $40 million they spent in total, not to mention interest and credit-card fees.

With this agreement, chances are slim we’ll ever find out how involved the president-elect was in allegedly ripping off thousands of customers. But even without a trial, there’s a lot to be learned from the details of Trump U’s 11-year saga. No other scandal of his campaign is so revealing of Trump’s attitude toward the alienated Middle Americans he’s pledged to represent.

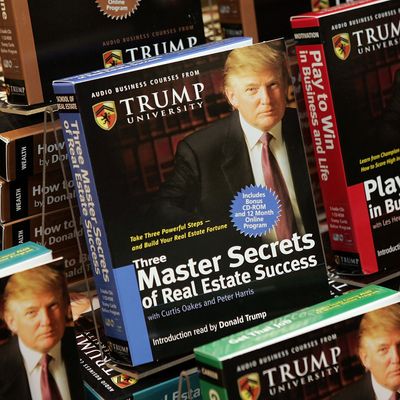

The program was hatched in 2004, when a management consultant named Michael Sexton approached Trump with the idea. The first season finale of The Apprentice had just aired that spring, drawing almost 30 million viewers, and Trump was the most famous tycoon in America. Sexton, who had an M.B.A. and a tech background, asked if he could license Trump’s name for an e-learning platform that would provide real-estate training on the web. Trump made a counter-offer: He would fund Trump University and give Sexton a stake. They worked out an agreement where Trump owned 90 percent to Sexton’s 4.5, and Sexton received a generous salary. The Trump University website was launched in 2005, and in-person seminars followed shortly thereafter.

The seminars were marketed via direct mailings and newspaper ads — all the better to reach elderly audiences. Altogether, the mailers blanketed 700 cities nationwide, from Phoenix to Schenectady. The real-estate mogul himself appeared in web videos, full of classic Trumpian promises: “We’re going to teach you better than the business schools are going to teach you, and I went to the best business school.” The instructors, he said, were all chosen by him personally, and were “absolutely terrific — terrific people, terrific brains, successful.”

The New York State Education Department warned the company early on that it was breaking the law by calling itself a “university,” since it wasn’t licensed and did not confer degrees. It apparently tried to skirt the warning by setting up a mail-drop office in Delaware, but it continued to operate out of the Trump offices in Manhattan.

By the time Kathleen Meese received her invitation in 2009, the operation had been running for four years, and the sales script was polished to a high gloss. (A copy has been released during the litigation, and it reads like a parody of cynical sales coaching: telling workers to be in a “Sales Mindset,” ready to “Sell, Sell, Sell!” After all, they were only paid on commission, not for actual teaching.) At the theater in Schenectady, Meese was surprised to see that Trump wasn’t present himself, because she’d been led to believe she could have her photo taken with him; instead there was just a cardboard cutout of his image. Still, she agreed to sign up for a three-day workshop at the price of $1,495, where the staffers said she’d learn everything necessary to launch her investment career.

The seminar was at a Hyatt hotel in another town upstate. Her instructor, Steven Goff, said he knew Trump through his brother and had worked with the mogul personally. “Mr. Goff made you feel that Donald Trump was going to review everything that was taught during the program,” Meese recalled later. (In other courses, instructors fabricated stories about having dinner at Trump’s house and said he often dropped in on seminars — which never happened.)

The lessons, she says, were “vague” and unhelpful. Then midway through, Goff took her aside and urged her to enroll with him as a personal mentor, via the “Gold” package, which would cost $25,000. She explained her son’s condition, but she says Goff pushed harder. “He said he had a son,” she recalled, “so he knew how family meant everything to me.” She says he guaranteed that she’d get her money back within 60 days, and that she could call him as much as she needed. The clincher was when he told the whole class he’d be working with Meese personally. Again she agreed to sign up.

But a few days after the seminar, she was reassigned to a different “mentor,” and she says he didn’t help her at all — only took her to some rental properties that weren’t for sale, and talked to the owners, so she could “see how to talk to people about properties.” The company wouldn’t refund her money, and she couldn’t reach any other instructors by phone.

Her experience squares with tactics prescribed in the staff manual. It tells staffers to focus on cultivating trust during the three-day workshop, and reminds them that “an attendee’s problem,” i.e. financial shortage, “represents a golden opportunity.” Some students were urged to cash in their 401k accounts, others to have their credit-card limits raised. Those who did were cheered by the staff, “like they had just been inducted into a fraternity,” another student recalled later.

Similar complaints were filed in at least 11 states, and some of the others are just as grim as Meese’s. One woman in Seattle, who was unemployed and had just suffered a stroke, said the instructors convinced her to max out her credit card to invest in additional classes. A 75-year-old man from Chula Vista, California, is still working at Walmart to pay off his credit-card debt from the program. Others were veterans and retired police officers. The Better Business Bureau received so many complaints it lowered the company’s rating to a D-minus.

In his defense, Trump has always pointed to a supposed 98 percent approval rating from students. But many of those upbeat reviews are from students in the free seminars, and a large share of the paying customers demanded refunds. Moreover, some of the plaintiffs have said they felt coerced to give positive reviews.

Meanwhile, the staffers weren’t all the “best of the best,” as Trump promised. When the Associated Press investigated 68 of them earlier this year, it found that half had personal bankruptcies, credit-card defaults, or other indicators of serious money troubles before they were hired to teach courses on subjects like “wealth building.” At least four had felony convictions, and one had allegedly threatened to kill his ex-wife. Many didn’t have college degrees and weren’t licensed to broker real estate.

The New York State Education Department pointed out again in 2010 that the company was breaking state law by calling itself a “university.” It changed its name to Trump Entrepreneur Initiative, but by then other attorneys general were prying into the company, and before long it shut down. Altogether Trump U had raked in some $40 million from more than 5,000 customers.

Trump personally collected about $5 million. He claimed he would eventually donate it to charity, but then said he’d returned it to Trump U after the legal troubles started.

The first lawsuit was filed in 2010, in San Diego, by a yoga instructor named Tarla Makaeff. She said she spent more than $60,000 on Trump University seminars, including interest and fees from her credit-card company, without gaining any useful real-estate knowledge or leads in exchange. The suit was later granted class-action status, so other former students stood to recover their tuition, too.

However, no one paid much attention, not even the local press in Southern California. After all, Trump has been involved in thousands of lawsuits throughout his career. The turning point came in 2013, when New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman filed his own lawsuit against the program, this time in a state-level court. “This is a very, very classic bait-and-switch scheme,” the attorney general said. “People were not taught real-estate secrets. It was a fraud.” Trump escalated the hype by calling Schneiderman a “total lightweight” who was “very unpopular.”

Later in 2013, another former student from California, Art Cohen, filed a third lawsuit under the federal racketeering law. If Trump’s company had lost this one, it would have been on the hook for $120 million, three times what the plaintiffs spent.

All three cases centered on the charge that the company deceived clients, with claims that Trump was handpicking the faculty, and with insinuations that he designed the curricula himself. On its face, this was hard to dispute. Staffers had claimed in seminars that the company was Trump’s “baby,” and that he owned it “lock, stock, and barrel,” according to court records. Advertisements showed his face next to messages like, “Don’t think you can profit in this market? You can. And I’ll show you how. Learn from my handpicked experts how you can profit from the largest real estate liquidation in history.”

But his own attorneys later said Trump had been “completely absent” and dismissed those messages as “classic sales puffery.” He only reviewed advertisements “very quickly” to see how he was portrayed, they said. There seemed to be broad agreement that the program wasn’t what Trump claimed. Much of the legal feuding was about procedure instead.

Trump’s election ratcheted up the pressure to resolve the cases without a trial. Besides the logistical problems his new schedule would have created, the prospect of an American president standing trial for fraud and racketeering didn’t bode well for foreign relations, let alone his domestic agenda.

In the days before the settlement, Richard Briffault, a law professor at Columbia University, said Trump’s situation had only one historical analogue: the lawsuit Paula Jones filed against Bill Clinton in 1994, claiming he’d sexually harassed her while he was governor of Arkansas. The Supreme Court ruled that being president didn’t make Clinton immune from lawsuits over what he’d done before taking office. “The theme of the Clinton case,” Briffault said, “is that he should be treated as an ordinary citizen — with appropriate modifications.”

However, in scale, the charge against Clinton didn’t approach the Trump University lawsuits. Christopher Peterson, a law professor at the University of Utah, released a paper in September, arguing that the accusations alone are grounds for impeachment. Of course, impeachment is politically inconceivable anyway, given that Congress is controlled by the Republicans. Peterson said the response to his paper had been only a “shrug” from Constitutional law-scholars, plus a mountain of hate mail from Trump supporters. “East Coast people think it’s a little bit gauche, I can tell,” he admitted.

In a way, Trump University is a simulacrum of Trump’s presidential campaign. Both relied on direct appeals to the downtrodden, especially people without much education. In both settings, Trump claimed he was acting in the public interest. (Because, after all, he’s a billionaire! What could he have wanted with their money, or with political office?) And both trafficked in suggestions that Trump was their personal ally against the economic forces that had beaten them down.

His rhetoric, when the New York attorney general sued him, was especially telling: He claimed that Schneiderman let “Wall Street rape everybody.”

It was as though he’d forgotten about those advertisements that touted Trump University’s Manhattan address as a symbol of its prestige. “Other people don’t have anyone to call,” they said. “But you’ve got Trump. You’ll call 40 Wall Street and they’ll walk you through.”

*This article has been corrected to show that Richard Briffault is a law professor at Columbia University, not New York University.