At first glance, the idea of a new National Reconstruction Memorial seems ill-timed. At this moment of great racial and political polarization, do we really need to dwell on a much earlier period of military confrontations and wholesale domestic terrorism over politics, culminating in failure and a virtual conspiracy to forget (or at least mis-remember) the whole thing?

Actually, it may be the perfect time for such a project, as three prominent historians argue in a New York Times op-ed this week.

The story of Reconstruction remains a rich and troubling one for a nation that prefers stories of progress over those of regression. It reminds us of the centrality of race-based slavery to our nation’s history; of the idealism of those, white and black, who sought to build a society based on racial equality upon the ashes of slavery; and of the violent overthrow of the experiment in biracial democracy. More broadly it reminds us that rights we sometimes take for granted can be taken away.

More immediately, the table has been set for such a memorial in the history-drenched locale of Beaufort, South Carolina, thanks to local (and bipartisan) initiative. President Obama has the power to make the memorial official before he leaves office.

Work on the monument is already underway. Community leaders in Beaufort have submitted a formal request to the National Park Service for a monument that encompasses key sites of emancipation and postwar community-building. In May, two South Carolina representatives — James Clyburn, a Democrat, and Mark Sanford, a Republican — sponsored a resolution to establish a national monument to the Reconstruction era. And last month, a group of 17 historians who have been helping the National Park Service study Reconstruction, as well as the American Historical Association and other professional historical groups, endorsed this effort.

I’d add to the historians’ arguments three very specific reasons a Reconstruction Memorial is an excellent idea right now.

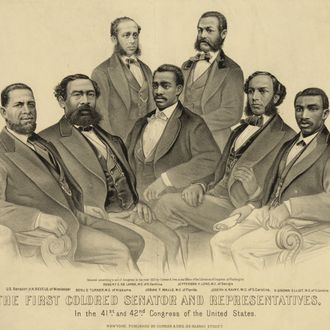

First, we need very specific reminders of the blood and toil involved in trying to secure the right to vote — and of the consequences, individually and nationally, of letting that right slip away for the most vulnerable Americans. For all the later talk (much of it explicitly racist) of corrupt state and local governments dominated by ex-slaves and carpetbaggers being enabled by Reconstruction, it represented a brief moment of full and equal rights (for men, anyway) of self-government in the South — soon to be swept away in most of the region by many decades of Jim Crow, “whites-only” elections, economic exploitation, and mass incarceration. Certainly those who like to caterwaul about the phantom menace of “voter fraud” or who treat the right to vote as simply a partisan plaything to be extended or withdrawn at the prevailing political party’s whim must be confronted with this history as often as possible.

Second, in this era of renewed interest in the Constitution (especially on the Right, but given the nature of the incoming administration in Washington, soon to be extended to the Left), it is essential that public discourse over the “Founders’ intent” include the full realization that the Constitution without the Reconstruction Amendments (the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery, the Fourteenth Amendment guaranteeing equal rights, and the Fifteenth Amendment protecting the right to vote) represented a failed design that inevitably led to a bloody Civil War. Claiming to revere the Constitution while ignoring these amendments, which crucially modified the states-rights and limited-government assumptions of the original document, is to adopt a neo-Confederate stance. “Constitutional conservatives” sometimes need to be reminded of this basic problem.

Third and perhaps more subtly, Reconstruction and its ultimate abandonment should remind us that while political and racial polarization are terrible things, reconciliation without justice is worse. In 1877, our country overcame a genuine constitutional crisis over a contested presidential election via a grand bargain between the two parties in which (according to most historians, anyway) Reconstruction and with it the guarantee of basic rights for African-Americans were sacrificed.

We’re still a decade away from the sesquicentennial of that fateful event, celebrated at the time (and for many decades later, thanks to what we might call the Birth of a Nation/Gone With the Wind view of Reconstruction) as a national triumph. Yes, we could use a memorial that sets the record straight and warns us against the perpetual peril of denying full citizenship to anyone in our midst. As a white Southerner old enough to remember the Jim Crow system Reconstruction might have prevented, I hope President Obama acts before the opportunity disappears.