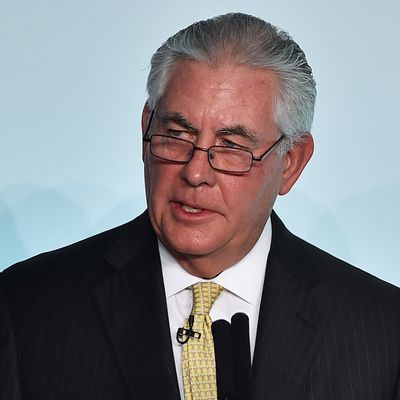

President-elect Donald Trump is reportedly set to nominate ExxonMobil CEO Rex Tillerson to be his secretary of State, according to Trump sources who spoke to NBC News, the New York Times, and others on Saturday. Those sources, per NBC, “cautioned that nothing is final until the president-elect officially announces it, likely next week,” but Tillerson did meet with Trump on Tuesday and again on Saturday. NBC additionally reports they were told that former U.N. ambassador John Bolton — one of the architects of President George W. Bush’s foreign policy and the Iraq War — would be made the deputy secretary of State to handle the department’s day-to-day management. The Times reports that Bolton is only one of the two finalists for the deputy job, as is Richard N. Haass, the president of the Council on Foreign Relations. Trump himself wouldn’t confirm the Tillerson pick on Sunday morning, though he praised the CEO both in a Fox News interview and on Twitter:

Should Trump select Tillerson to head the State Department, it will apparently be on account of Trump and his advisors preferring the executive’s extensive experience negotiating international business agreements (per the Times, Trump’s closest advisors, Steve Bannon and Jared Kushner, both pushed for the pick). Adds the Washington Post, Trump decided on Tillerson “because he projects gravitas, is regarded as a skillful manager and personally knows many foreign leaders through his dealings on behalf of [ExxonMobil.]” Tillerson is yet another wealthy business leader with little or no government experience, characteristics that appear to be assets if one wants to be in Trump’s cabinet.

Tillerson’s business experience, however, is also sure to complicate, if not necessarily prevent, his confirmation. Of particular concern is the CEO’s close ties to Russian president Vladimir Putin and how he has long worked to strengthen U.S.-Russia relations. As The Wall Street Journal reported on Friday, according to Tillerson’s friends and associates, “[F]ew U.S. citizens are closer to Mr. Putin than Mr. Tillerson, who has known Mr. Putin since he represented Exxon’s interests in Russia during the regime of Boris Yeltsin.” Indeed, Putin awarded Tillerson with Russia’s Order of Friendship — one of the country’s highest honors — in 2013. In 2011, the CEO negotiated a $500 billion Arctic oil contract between ExxonMobil, the Kremlin, and the state-owned Rosneft oil company, but the deal was suspended once Russia invaded Ukraine in 2014, and was subsequently punished with U.S. economic sanctions by the Obama administration, a policy which has reportedly cost ExxonMobil more than $1 billion.

Tillerson has, unsurprisingly, spoken out against U.S. sanctions on Russia, remarking at a company meeting in 2014 that “we always encourage the people who are making those decisions to consider the very broad collateral damage of who are they really harming,” while also explaining that ExxonMobil doesn’t support sanctions because “we don’t find them to be effective unless they are very well-implemented comprehensively — and that’s a very hard thing to do.”

Any Trump cabinet pick with ties to Russia, including Tillerson and national-security-advisor nominee Michael T. Flynn, is also now likely to face even more scrutiny following reports that Russia intervened in the U.S. election in order to help Trump win.

Tillerson, a 64-year-old Texas native with a net worth of more than $150 million, has no government or public-sector experience, which would be a first for any U.S. secretary of State. He also has few known foreign-policy views beyond those expressed in the interests of his company. Tillerson is a strong supporter of free trade, but Trump repeatedly railed against trade deals during his presidential campaign, so it’s not clear if Tillerson would continue to support them once he’s running Trump’s State Department. Regarding climate change, Tillerson told ExxonMobil shareholders in May that “we believe that addressing the risk of climate change is a global issue,” which requires the co-operation of governments and businesses (though, that is a decidedly recent conclusion for the company). Trump has called climate change a China-perpetrated hoax and this week nominated a climate-change denier to run the Environmental Protection Agency.

The potential for conflicts of interest for Tillerson as America’s top diplomat don’t end with Russia either. Tillerson has worked for ExxonMobil for 41 years and has been its chair and CEO since 2006. The corporation is the world’s eighth-largest company by revenue, has operations in more than 50 countries, and explores for oil and gas on six continents. As the Journal also notes, although Tillerson was planning to retire next year, he still has retirement funds worth tens of millions of dollars that could be impacted by U.S. foreign-policy decisions.

Obviously, Tillerson’s nomination would be controversial, even for the norm-demolishing Trump team, and not just among Democrats. Some Republicans have already reportedly warned the Trump camp against working with Russia, and on Friday, after the president-elect’s preference for Tillerson was first reported, there were at least some indications the pick could face resistance within the party, like this tweet from one of Senator John McCain’s closest confidants:

McCain echoed Salter’s comment on Saturday, telling CNN he had major concerns about Tillerson’s relationship with Putin, who McCain called a “thug and a murderer,” and if those concerns aren’t resolved, he will vote against Tillerson’s confirmation. Also on Saturday, Republican senator Lindsey Graham spoke out against Russia more generally, responding to Friday’s news about Russia’s hacker-interference in the election:

[You don’t] have to be Sherlock Holmes to figure out what Russia is up to — they’re trying to undermine democracies all over the world. Russia is trying to break the backs of democracies — and democratic movements — all over the world. I’m not challenging the outcome of the election, but very concerned about Russian interference/actions at home and throughout the world.

Senator Marco Rubio sounded skeptical on Sunday as well:

Meanwhile, former U.S. ambassador to Russia, Michael McFaul, who has seen the ExxonMobil/Russia relationship up close, insisted that if Tillerson is selected, Congress will need to establish “an independent, bipartisan commission on Russian meddling” in the U.S. government. McFaul has already been very vocal in his opposition to Tillerson’s nomination as well:

But Suzanne Maloney, a respected foreign-policy analyst at the Brookings Institute who once worked for ExxonMobil, pushed back on the blanket criticism against Tillerson on Saturday (via a tweetstorm, but expanded below), insisting that business leaders can become effective policymakers:

A lot of the negative/shocked reactions to Rex Tillerson as SecState seem to come from people w/limited understanding of private sector. … The presumption that Tillerson must be a pro-Putin ideologue because he and ExxonMobil did business successfully in Putin’s Russia is simplistic and patronizing. Oil folks know stuff: anyone who manages multi-billion dollar, multi-decade projects needs deep, nuanced understanding of political context. In this sense, Tillerson’s business experience gives him a very different lens than other executives in Trump’s cabinet, and [one that’s] very relevant for diplomacy. Inside-the-Beltway types don’t have a monopoly on wisdom about international affairs: My ExxonMobil colleagues had a sharp grasp of regional dynamics. In [the] run-up to [the] Iraq invasion, I heard far more skeptical questions and realistic scenarios from energy executives than from most DC pundits, Republican or Democrat. Tillerson rose to top of a company that prizes technical excellence, rock-solid financials, hard work, and integrity. The State Department could do a lot worse.

Then again, as some responded to Maloney, energy-business savvy doesn’t necessarily translate when it comes to nuclear weapons, NATO, human rights, or climate change, and making deals for mutual profit is actually nothing like making deals to secure alliances or prevent bloodshed. In addition, the State Department is no businesslike hierarchy, though considering another dimension of the pick, ExxonMobil is no ordinary business either. The journalist Steve Coll wrote a book called Private Empire about the company in 2012. Here is part of Adam Hochchild’s take on it for the Sunday Book Review, in which he illustrates how ExxonMobil is so large and so powerful that it effectively acts as its own government:

Exxon Mobil’s foreign policy, orchestrated by a political division including National Security Council and State Department alumni, sometimes coincides with that of the United States, and sometimes diverges. For example, the corporation had no enthusiasm for invading Iraq. Yes, Iraq has all that oil, but with most remaining reserves ever harder to get at, oil executives knew that whoever ran Iraq would ultimately depend on the technology and capital of the Exxon Mobils of the world. And yes, it might have been nice to own Iraqi oil wells outright, but long-term stability and security mattered more. […]

Just like the British South Africa Company, which pioneered the use of Hiram Maxim’s machine gun during the Matabele War, Exxon Mobil has its own armies — and, in these days of outsourcing, also hires those of others. In Chad, its 2,500 security men patrolled the countryside in white radio-equipped S.U.V.’s, watching for guerrillas as the company set up an intelligence operation bigger and better than the local C.I.A. station. In the war-racked Niger Delta, it gave boats to the Nigerian Navy, deployed its own vessels at sea to scout for pirates and “recruited, paid, supplied and managed sections of the Nigerian military and police.” On their uniforms, the Nigerian police sported Mobil’s familiar red flying horse. In Aceh, Indonesia, Mobil paid the salaries of Indonesian counterinsurgency forces who tortured and murdered prisoners on company property. Payments kept flowing even after the American government cut off aid to the Indonesian military because of such abuses.

Coll also points out that while ExxonMobil executives are good at figuring out the technical, logistical, and financial components of the company’s international entanglements, they aren’t as good at taking advice about the human factor of their deals. In that sense, as Coll put it to the Times on Saturday, the company “keeps the windows closed.” He later elaborated on his views of ExxonMobil and Tillerson in The New Yorker on Sunday:

The goal of ExxonMobil’s independent foreign policy has been to promote a world that is good for oil and gas production. Because oil projects require huge amounts of capital and only pay off fully over decades, Tillerson has favored doing business in countries that offer political stability, even if this stability was achieved through authoritarian rule. As he once put it, “We’re really thinking about, well, what is it going to be fifteen, twenty years from now, and so what are the conditions in some of these countries likely to be?” The corporation maintains a political-intelligence and analysis department at its headquarters in Irving, Texas, staffed by former government officials, which tries to predict the stability of countries many years into the future by analyzing demographics, employment, political control, and other “fundamentals.” Although ExxonMobil has a stated policy of promoting human rights, and has incorporated the advice of human-rights activists in its corporate-security policies, it nonetheless works as a partner to dictators under a version of the Prime Directive on “Star Trek”: It does not interfere in the politics of host countries. The right kinds of dictators can be more predictable and profitable than democracies.

Overall, Coll is skeptical about Tillerson’s chances for success as secretary of State, noting the particularly strong division between public and private-sector ways of thinking, especially when it’s somebody from ExxonMobil:

Although ExxonMobil hires former State Department, Pentagon, and C.I.A. officials from time to time in order to bolster its political analysis and negotiations, some of the Exxon executives I interviewed spoke about Washington with disdain, if not contempt. They regarded the State Department as generally unhelpful, a bureaucracy of liberal career diplomats who were biased against oil and incompetent when it came to sensitive and complex oil-deal negotiations. They managed Congress defensively, and as just one capital among many in the world, a place more likely to produce trouble for Exxon than benefits. In nominating Tillerson, Trump is handing the State Department to a man who has worked his whole life running a parallel quasi-state, for the benefit of shareholders, fashioning relationships with foreign leaders that may or may not conform to the interests of the United States government. In his career at ExxonMobil, Tillerson has no doubt honed many of the day-to-day skills that a Secretary of State must exercise: absorbing complex political analysis, evaluating foreign leaders, attending ceremonial events, and negotiating with friends and adversaries. Tillerson is a devotee of Abraham Lincoln, so perhaps he has privately harbored the ambition to transform himself into a true statesman, on behalf of all Americans. Yet it is hard to imagine, after four decades at ExxonMobil and a decade leading the corporation, how Tillerson will suddenly develop respect and affection for the American diplomatic service he will now lead, or embrace a vision of America’s place in the world that promotes ideals for their own sake, emphatically privileging national interests over private ones.

(Be sure to read Coll’s expansive 2012 New Yorker investigation of ExxonMobil’s U.S. political influence, as well.)

Buzzfeed News looked at Tillerson’s roundabout credentials earlier this week, too, highlighting how international oil-exploration deals can require negotiating with unstable nations whose shifting policies need a lot of convincing. David Victor, a professor of international relations at the University of California, San Diego, notes: “[Tillerson] spent a huge amount of time trying to figure out whether governments are serious about reforms that they’re announcing. That skillset around being able to assess the credibility of government is an extremely important one.”

Victor also said he believes someone like Tillerson, if leading America’s diplomacy, would be much less likely to recommend the use of sanctions against a country on principle because he is so familiar with the short-term business consequences those sanctions often result in. If true, that mindset wouldn’t bode well for the recent, U.S.-led, Western attempts to curb Russia’s growing influence and aggression in Europe, the Baltic states, and in Syria. And because President Obama imposed the 2014 sanctions on Russia by executive order, Trump can undo them just as easily once he’s the executive doing the ordering. Then again, Trump choosing a secretary of State with a general aversion to sanctions would also have an unknown impact on the Obama administration’s nuclear deal with Iran — a deal that was largely achieved as a result of pressure from U.S. sanctions on the Iranian regime and which Trump and his advisors have promised to cancel and “renegotiate.”

Regardless, if Tillerson gets the nod, Democrats are already promising to make his confirmation a painful and informative process. Politico reported earlier this week that while Senate Democrats won’t have the ability to block his nomination, they are still looking forward to grilling Tillerson under oath on issues like climate change — particularly what the Trump administration plans to do (if anything) about the problem, and whether or not ExxonMobil has deliberately downplayed the threat of global warming and its links to the burning of fossil fuels, as some investigations have claimed. Put another way:

“There are plenty of other candidates for secretary of State who don’t bring that kind of baggage to the table and would not engender that kind of firestorm at confirmation hearings,” said Peter Frumhoff, director of science and policy at the Union of Concerned Scientists. “Of the candidates I’ve seen, none would fare worse than Rex Tillerson.”

Politico also points out that the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, which has to approve the nomination, only has a ten-to-nine, Republican-to-Democrat split, meaning a single opposing Republican on the committee could ally themselves with Democrats to block the pick. That’s probably still unlikely, but regardless of what happens during the confirmation process, Trump and his team clearly don’t care, at least for now, about accusations of pro-Putin sympathies. How that plays out with regards to future U.S. foreign policy is becoming easier to guess.

Then again, as longtime Russia watcher Julia Ioffe explains at Politico, if Tillerson is as smart as Trump thinks, then maybe he can explain to the president-elect what friendship with Putin is really like:

The lesson of Putin’s 16-year tenure is a lesson that all businesspeople, foreign and domestic, have learned: to do business in Russia, you have to be on good, personal terms with Putin and [Rosneft-head Igor] Sechin. And you have to understand that those two gatekeepers to Russia’s riches are fickle and sadistic, and, as former KGB operatives, know little of real friendship. To do business in Russia—both for Exxon Mobil and for Tillerson’s own massive retirement fund whose fortunes would rise significantly if a Trump White House lifted sanctions—you have to dance to Putin’s tune, and take whatever favors and humiliations he sends your way. Putin may act a friend and pin state medals on your breast, but he is, ultimately, a cynic. And to play ball with him, you have to be a cynic, too. Forget your honor, your rule of law, your independent judiciary, your human rights, your international law, and focus on the gold coins he throws to your feet. And forget looking dignified as you gather them up.

This post has been updated throughout to reflect additional context and analysis.