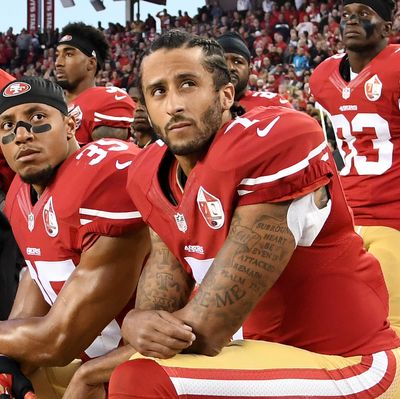

In all the NFL kerfuffle, we’ve lost sight, it seems to me, of precisely why Colin Kaepernick and now many others have been kneeling. He’s not kneeling because he’s unpatriotic; he’s kneeling because he is patriotic, and he wants his country to live up to its ideals. In his words: “I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of color. To me, this is bigger than football and it would be selfish on my part to look the other way. There are bodies in the street and people getting paid leave and getting away with murder.” His core issue seems to be police interaction with black men, especially shootings. His teammate, Eric Reid, wrote an op-ed on Monday where he elaborated:

In early 2016, I began paying attention to reports about the incredible number of unarmed black people being killed by the police. The posts on social media deeply disturbed me, but one in particular brought me to tears: the killing of Alton Sterling in my hometown Baton Rouge, La. This could have happened to any of my family members who still live in the area.

Let’s unpack Reid’s concern at “the incredible number of unarmed black people being killed by police.” My colleague Eric Levitz this week put a number on it: “We live in a country where police gun down 1,000 unarmed, disproportionately black citizens on an annual basis.” He gets that number from the recent Washington Post attempt to nail down specific data on how common this is. But he falls understandably into the trap that many of us do. Thanks to numerous horrifying videos, and some horrible cases, like those of Philando Castile and Eric Garner, we have come to assume that unarmed black men are being gunned down in large numbers. But the Washington Post data does not, in fact, back that idea up.

The Post has indeed found that there’s a strikingly consistent number of fatal police shootings each year: close to 1,000 people of all races. But that figure includes the armed and the unarmed. Fatal police shootings of the unarmed — the issue Kaepernick and Reid cite — are far fewer. In the first six months of this year, for example, the Post found a total of 27 fatal shootings of unarmed people, of which black men constituted seven. Yes, you read that right: seven. There are 22 million black men in America. If an African-American man is not armed, the chance that he will be killed by the police in any recent year is 0.00006 percent. If a black man is carrying a weapon, the chance is 0.00075. One is too many, but it seems to me important to get the scale of this right. Our perceptions are not reality.

In other policy areas, left-liberals tend to agree with me on this general logic. They usually insist on not confusing an anecdote for solid data. They point out, for example, the infinitesimal chance that you will be killed by a terrorist in order to puncture the compelling and emotional narrative that we are a nation under siege by jihadists. They note that the public’s view that crime has been rising is, in fact, a fiction drummed up by Trump — and they cite the kind of data I just provided to prove it. But when it comes to race and police shootings, the data take second place to emotion. This is not bad faith on the part of left-liberals. It’s rooted in an admirable concern about a vital topic — the use of violence by the state against citizens. And I have no doubt at all that Kaepernick and Reid are sincere, and I absolutely defend their right to protest in the way they have, and am disgusted by the president’s response. But on the deaths of unarmed black men, the left-liberal characterization of the problem just does not match the statistical reality.

How about looking at all such deaths, armed and unarmed, and the context for them? One avenue for understanding what’s going on is to ask a national sample of citizens, black and white, about their interactions with police. A Cornell Ph.D. student, Philippe Lemoine, has dug into exactly that: by examining the data from the Police-Public Contact Survey, conducted by the Bureau of Justice Statistics. This is testimony from black people themselves, not the police; it’s far less tainted than self-serving police records.

It’s a big survey — around 150,000 people, including 16,000 African-Americans. And it provides one answer (although not definitive) to some obvious questions. First off, are black men in America disproportionately likely to have contact with the police? Surprisingly, no. In the survey years that Lamoine looked at, 20.7 percent of white men say they interacted at least once with a cop, compared with 17.5 percent of black men. The data also separates out those with multiple encounters. According to Lemoine, black men (1.5 percent) are indeed more likely than whites (1.2 percent) to have more than three contacts with police per year — but it’s not a huge difference.

On the key measure of use of force by the cops, however, black men with at least one encounter with cops are more than twice as likely to report the use of force as whites (one percent versus 0.4 percent). That’s the nub of it. “Force,” by the way, includes a verbal threat of it, as well as restraining, or subduing. If you restrict it to physical violence, the data is worse: Of men who have had at least one encounter with the police in a given year, 0.9 percent of white men reported the use of violence, compared with 3.4 percent of black men. (For force likely to cause physical injury, i.e. extreme force, however, the ratio is actually better: 0.39 percent for white men compared with 0.46 percent of black men.)

What do we make of this data? I think it shows the following: that police violence against black men, very broadly defined, is twice as common as against white men, and narrowly defined as physical force, three times as common, but that there’s no racial difference in police violence that might lead to physical harm, and all such violence is rare. (Recall that the 3.4 percent of black men who experience violence at the hands of the police are 3.4 percent of the 17.5 percent of those who have at least one encounter with the cops, i.e., 0.5 percent of all black men.)

Is “rare” a fair judgment? It’s certainly a subjective one, and I do not know how I would feel if there were a 0.5 percent chance that any time I encountered a cop, I could be subjected to physical violence, as opposed to the 0.2 percent chance that I, as a white man, experience. What makes it worse for black men, of course, is something called history, in which any violence by the state rightly comes with immensely more emotional and political resonance — and geography. Police violence may be rare across the entire country, but it is concentrated in urban pockets, where the atmosphere is therefore more fearful — and there’s a natural tendency to extrapolate from that context.

Specific horrifying incidents — like Alton Sterling’s death — operate in our psyches the way 9/11 does. It understandably terrified Eric Reid — but also distorted his assessment of the actual risk that one of his family members could suffer the same fate. It’s true, too, that the huge racial discrepancy in the prison population affects our judgment. You could also argue that lynching was statistically very rare in the past, but it instilled a real terror that belied this real fact. The problem with this analogy, however, is that we’re not talking about extralegal lynchings by civilians, in the context of slavery or segregation or state-imposed discrimination. We’re talking about instantaneous decisions by cops, often in contexts where their own lives are at stake as well. Their perspective — and many of these cops are also African-American — matters as well.

This is the balance we have to strike. We can and should honor the spirit of the protests. But we cannot allow ourselves to let emotion, however justified, overwhelm reality. To give the impression that police are gunning down black men in America solely because they are black is a dangerous exaggeration that undermines the vital work of the police. It’s also a profound indictment of a nation that America, in this respect, simply doesn’t deserve.

I watched Jeremy Corbyn’s annual address to the Labour Party Conference this past week in Britain, and I think I saw the next prime minister of Britain. It still shocks me to say this. Not so long ago, the far-left maverick was dismissed as utterly unelectable — in ways even more emphatic than Donald Trump in the primary season. After the Brexit referendum, two-thirds of his shadow cabinet quit, and 80 percent of his fellow Labourites in the House of Commons expressed a formal no-confidence vote in his leadership. Only a few months ago, his party was nearly 20 points behind the Conservatives in most polls. But Prime Minister Theresa May’s simply dreadful election campaign earlier this year gave Labour its biggest surge in support from one election to the next since 1945, and Labour has been polling a little ahead of the Tories now since June.

But the election wasn’t just an anti-May vote. It was also a pro-Corbyn one, especially among the rising generation. Millennials, having never experienced socialism, love it. And Corbyn is on the leftist edge of socialism. He’s for huge increases in taxation and public spending, he promises free college for all, he wants to instate rent controls across Britain’s major cities, and, in his speech last Wednesday, he described gentrification as “social cleansing.” Most of his proposals would add mountains of debt to the British economy, and he doesn’t really care. Austerity is so over. He is a proud isolationist — finding almost no rationale for Britain’s intervening militarily anywhere on the planet. Personally, he favors a U.K. withdrawal from NATO, backed Chavez in Venezuela, and has called members of Hamas and Hezbollah “friends.” He individually favors ending Britain’s nuclear deterrent, but has not imposed this policy on the party as a whole. He’d like to abolish the monarchy. He has long been a left-wing critic of the E.U. and a believer in a united Ireland. This makes him a bigger leap to the left than Trump is to the right. It’s as if Roy Moore were the GOP nominee — and leading in the polls.

At this point, then, it seems to me that he cannot be called an extremist, if only because the extreme is now very much part of the mainstream. And in a two-party system, an enormous swing leftward matters. This week revealed that his grip on Labour is now fully solidified and the cult of Corbyn entrenched. His speaking skills have vastly improved as his anti-charisma has become the new charisma. And the Tory Party, now trying to accomplish Brexit from a much-weakened parliamentary base, is both adrift and divided. This past week, for example, the foreign secretary, Boris Johnson, came out publicly in favor of a swift exit from the E.U., a week after May gave a speech asking for two more years for the U.K. to transition. A divided right in disarray? And a 68-year-old leftist leading the left? The case for Bernie is surely strengthened.

But I suspect another key factor is Corbyn’s effortless Englishness. He is a very specific character — a very English leftist. He’s mild-mannered in speech, even as his ideas are radical. In the last election campaign, he came off as an ordinary man of the people, as opposed to May’s weird and contrived public persona. In a classic moment since, in the wake of the fire that gutted a major residential tower in London, he was almost immediately at the scene, comforting relatives and bonding with them. May initially kept her distance, and then was heckled and booed as she finally arrived.

Most important, Corbyn bottles his own jam and is a passionate fan of manhole covers. He takes photos of them, everywhere he goes, one of a tribe of “drain-spotters,” admiring different varieties of cast-iron fixtures. The Independent interviewed one of his fellow grid-iron obsessives last year. He said: “We’re just middle-aged dads. There is a lot of silliness to it. Some of it has to do with an appreciation of lumps of metal in the ground, but it’s also about people who might not otherwise meet getting together and talking about nothing in particular over a pint.”

And what could be more English than that?

I’ve been reading Bob Wright’s new book Buddhism Is True. I’d recommend it alongside Sam Harris’s book, Waking Up, as a fantastically rational introduction to meditation. As such, it constantly made me smile a little, and occasionally chuckle. Maybe it’s because I’ve known Bob since we were colleagues at The New Republic many moons ago and so I hear his dry personality crackling ever so subtly throughout the prose. But it’s also because what you get from both Wright and, to a lesser extent, Harris (full disclosure: Sam is also a friend) is an almost pathologically non-metaphysical version of what we are used to calling a “religion.” Both construct a rigorous argument for the entirely worldly benefits of meditating every day; but Bob surpasses even Sam’s in his wry, self-deprecating, and brutally empirical guide to the avoidance of suffering. Evolutionary biology, neuroscience, and psychology are the foundation of Buddhism Is True. And I find much of it both intellectually convincing, and also recognizable with my own developing practice.

And that’s what I find intriguing about both books: Can you mount a thoroughly atheist defense of what most of us would call religious practice? Pascal pioneered this in a way: At one point in his Pensées, he argues for the practice of religion as a means to believing in it. And doing something spiritual, rather than believing in its metaphysics, is arguably the best entry point for most modern, educated Americans with respect to religious faith. We are not just minds, we are bodies. And training our bodies as well as our minds is what religions have always done; it’s the definition of ritual. I have found Bob’s and Sam’s version of Buddhism to be extremely helpful as a Christian whose church has casually tossed away so may of its ancient rites. Meditation requires discipline and doing something with our minds and bodies. And those are, paradoxically, the most powerful avenues for liberation and being. If that’s one way to reintroduce religious life to a secularized world, I’m all for it. Even though I believe, unlike Bob or Sam, that it’s just the start of a journey, rather than its destination.

See you next Friday.

Correction: The likelihood of an unarmed or armed black man being killed by police in given year, based on PPCS data, were both updated post-publication to account for a math error.