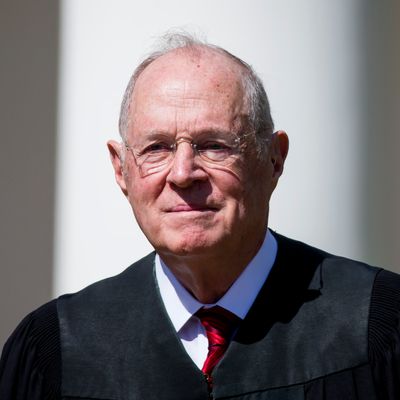

The retirement of Anthony Kennedy is an obituary for conservatism in America.

Kennedy’s pragmatic libertarianism — his belief in limited government, pluralism, moderation, and social cohesion — didn’t fit into either of our two political tribes’ worldview. He favored marriage equality but also the religious freedom of fundamentalists; he opposed racial preferences but found a way to accommodate some version of affirmative action; he believed in free markets but saw a role for government in preventing climate change; he sided with the conservatives on the court much of the time (including in his final term) but defended the habeas corpus rights of Gitmo prisoners, ended the death penalty for the mentally ill and minors, protected the right to burn the flag, and when push came to shove, defended Roe. For all this, he frustrated a lot of people, in both tribes. Many Republicans loathed what his rulings meant for gay equality, affirmative action, abortion, and his refusal to be an Antonin Scalia clone. They mocked his rhetoric for its highfalutin vagueness. Many Democrats expressed their contempt for him as he left, decried his consistent federalism, and simply couldn’t grasp how a social moderate could also favor defending the rights of fundamentalists unfairly treated by the state government or of big money in politics because of the First Amendment.

I have to say, I respected him for all the reasons the partisans hated him. What he was able to do was to hold two ideas in his mind at the same time: that history moves forward and laws and institutions need to adjust to those changes or die; and that the core conception of individual liberty should remain the animating principle of America and the West. I see this most clearly in his weighing of religious liberty with gay rights. He was intent on showing how compatible they ultimately were, if only individual freedom, moderation, and civility were allowed to do their work.

For me, his greatest work was in Lawrence v. Texas. His ruling was a defense of privacy that simply refused to consider heterosexual sodomy in any way superior to homosexual sodomy. And it was that refusal to prioritize the stigmatization of homosexuality over core human privacy that showed his deeply conservative readiness to adjust to the evolution of society. He saw gay people as fully citizens and fully human beings. He didn’t give us marriage equality any more than Obama did. But he listened to our arguments, saw our humanity, nudged marriage rights into legal existence, and defended them to the end.

This, to my mind, is the conservative temperament, fully understood. I can hear the howls of those who believe this definition is too esoteric and precious to mean anything in the American case right now. And, sure, the howlers have a point. I’m with David Brooks in his view that Republicanism has become conservatism’s worst enemy — worse even than the social-justice left. (I just reached that conclusion 15 years ago. I even wrote a book about it!) But I’d argue that this variety of conservatism is still essential to the project of liberal democracy, that reviving some of it is our only way out of gridlock, and its eclipse is a sign of how great the danger now is.

The key to this conservatism is restraint, reform, and concern with the stability of the society as a whole. Conservatives see the modern liberal order as a fragile, precious, and rare historical human achievement, innovated first by the British and then the Americans, conjuring a temperament and politics aimed at keeping the peace, preventing civil conflict, sustaining individual freedom against the mob or the government, generating prosperity, and moving right or left as conditions demand. Conservatism is not designed to usher in a new age, banish injustice, pursue “progress,” or remake human nature. It is indeed, in many instances, justice deferred. But without its attachment to precedent, to gradual change, to evolution rather than revolution, chaos and convulsion would make any justice unsustainable.

It’s not an emotionally satisfying tradition. The point is merely to keep liberal democracy vibrant, to sustain its legitimacy, and to protect its institutions. That’s why I favor a slowdown in immigration (too much demographic change too fast can destabilize a society); and why I favor more redistribution through taxes right now (because economic and social inequality are delegitimizing the entire capitalist order). And that’s why I loved Barack Obama. In his heart and mind, he is and was a moderate conservative, trying to blend new social realities with the long story of America, rescuing capitalism from itself, extending health care but through the market, shifting foreign policy incrementally toward Asia, and ending irrational, budget-busting, entropy-creating wars. He desperately tried to keep this country in one piece, against foam-flecked racism and know-nothingism on one side and left-wing ideological purity and identity politics on the other. And he almost did.

And this is why I despise Donald Trump: He exhibits no concern for the broader social good if it in any way conflicts with his own immediate psychic needs. He is indifferent to the collateral damage of his ego. He has embraced the most dangerous form of identity politics — that of the majority. There is not an institution or custom or alliance or constitutional norm Trump won’t vandalize at a second’s notice. He cares little for the generations ahead of us (see the debt and the environment); nor respects the wisdom of the past (see his desire to obliterate the idea of an independent Justice Department or the NATO alliance); he is a lonely, maladjusted id, with Western civilization as a plaything in his hands. And Republicanism — in its shameful embrace of this monster, its determined rape of the environment, destruction of our fiscal standing, evisceration of our allies, callousness toward the sick, and newfound contempt for free trade — has nary a conservative bone in its putrefying body.

A liberal society is always in need of this conservatism. The greatest recent philosopher in this tradition, Michael Oakeshott, described the kind of conservative politician he favored, and he used George Savile’s term for such a character: a “trimmer.” His account reads pretty much like Anthony Kennedy:

The ‘trimmer’ is one who disposes his weight so as to keep the ship upon an even keel. And our inspection of his conduct reveals certain general ideas at work … Being concerned to prevent politics from running to extremes, he believes that there is a time for everything and that everything has its time — not providentially, but empirically. He will be found facing in whatever direction the occasion seems to require if the boat is to go even.

No figure is more mocked or ridiculed in our contemporary culture than this kind of moderate. And yet no one right now is more integral to the survival of our way of life.

This matters. The displacement of this kind of conservatism by political ideology, religious fundamentalism, and constitutional recklessness should not just be of concern to those on the center-right. It should concern Democrats as well, whether liberals or leftists. Because Republicanism is a wrecking ball against any kind of balance or continuity in our society. It refuses to share power, to wait its turn, to see the importance of liberalism as its foil. And because of this Republican degeneracy, it has fallen in recent times to the Supreme Court to preserve the remaining shreds of the conservative disposition. The Court has become indispensable to forging the essential compromises that Congress won’t. In fact, given a rogue presidency, it’s now the only institution where some sort of moderate conservatism can flourish. And Kennedy was critical to that enterprise. Now that he is gone, there is only Chief Justice John Roberts to prevent the cold civil war from getting hot. And Roberts — for all his rescue of the ACA — is not likely to fill the Kennedy void.

So we descend another stair toward a republic so divided and so decadent and so incapable of give-and-take that it’s almost begging for a tyrant to impose his will. And that’s why the next few months are so vital. They’re our only chance to stem the slide. Although I deeply sympathize with those, like Chuck Schumer, who want to postpone the hearings until after the midterms in the wake of the Merrick Garland precedent, I simply don’t see how the Democrats can force it. With Harry Reid’s abolition of the judicial filibuster, and Mitch McConnell’s extension of that to Supreme Court nominees — both direct blows to liberal democracy — they’re out of constitutional options. I also don’t see much of a chance of flipping the Senate in November either, which is the relevant practical question when considering delaying the vote. And leaving it up in the air sure would mobilize the Democratic base — but it would light a hell of a fire under the GOP as well.

And when we look around for a conservatism that would seek some moderation at this juncture, we see only cowardice from elected Republicans. Jeff Flake could slow the nomination down, or demand a moderate nominee for his vote, but he has already folded. Susan Collins and Lisa Murkowski could make their Senate votes contingent on a commitment to defend Roe and Obergefell. But I doubt they will. Moderate Democratic senators in red states could gum up the works — but are too afraid of their Trump-supporting voters. Nothing can stop Trump from further dividing the country now, or completely transforming the GOP into his personal, extremist cult. What he should do, if he gives a damn about this country’s stability, is to pick someone in Kennedy’s mold. Instead, he’ll likely pick the most inflammatory candidate he can find, thrill to the response he will get from the left, pour some more gasoline on the immigration issue, and energize his base for the midterms. And if he isn’t checked by at least one half of the Congress, it’s a swift slide toward civil unrest, and further power grabs by the virtual tyrant.

All we can do is vote, and hope the blue wave isn’t just another elite delusion. I have hope in that regard — but no optimism.

The Differences Testosterone Makes

I must say, I’m grateful to Katrina Karkazis for engaging in the debate about testosterone and gender. Her essay in The New York Review of Books sure beats the usual gender-theorist approach — which is to gingerly step around the giant tumescent elephant in the room of their social constructionism. But as an argument, it also reveals why gender theorists avoid the subject. Karkazis’s case is so weak, it all but proves my point.

Her first assertion is that the countless, endless testimonies of almost everyone who has experienced suddenly higher levels of testosterone are too subjective to be reliable. It’s all a placebo effect, she wants us to believe. If you want to think that T will butch you up, you’ll insist that it has. In other words, testosterone is a kind of masculinist delusion, a device to fool yourself into thinking that there are actual physiological and psychological differences between men and women. The countless individual stories that tell a different story are merely a way to “reinforce shop-worn ideas of male-female difference.”

I don’t think this argument should be dismissed. The placebo effect is real. But the sheer consistency of the first-person accounts, alongside the fact that testosterone is, excluding surgery, literally the one thing that turns a default female into a male, alongside countless studies of behavior under the influence of low and high testosterone, certainly suggests that something real is going on.

Karkazis, to her credit, recounts many of the accounts that refute her position. She tells the story, for example, of gender theorist Paul B. Preciado who was intent on taking testosterone to prove that, in his words, “testosterone isn’t masculinity. Nothing allows us to conclude that the effects produced by testosterone are masculine.” But in a case where the placebo effect would presumably be reversed, here is how Preciado described the impact: Testosterone created “excitation, aggressiveness, strength,” and an “explosion of the desire to fuck, walk, go out everywhere in the city.” Oh well. Then Karkazis cites a “butch dyke” with a beard, Griffin Hansbury, who transitioned with hormone supplements. He didn’t think testosterone made him any more masculine than he was as a “butch dyke,” at least “outwardly.” And then Hansbury goes and gives an interview about his experience and blurts out, “I became interested in science, I found myself understanding physics in a way I never had before.” Dammit. Even trans people — the omniscient oracles for the social-justice left — can’t toe the line.

Which draws Karkazis to this concession: “I don’t mean that T is immaterial, imaginary, or ineffectual, or that our scientific or experiential knowledge of T is completely false.” Science and human testimony can’t be explained away entirely, you see. Just almost entirely: Listening to science or individual testimony runs the risk of “naturalizing the difference [between men and women] and obfuscates how our very experience is structured by social and historical forces and the interpretive frameworks we derive from them. There is no experience outside these constitutive conditions.”

And this is her core case. Humans have no experience outside the social constructions they live in. Nature, as an entity outside those constructions, doesn’t exist, and therefore cannot be a valid form of critique. This is a world in which humans are not animals, and have never experienced natural selection, or evolved a reproductive strategy around sex. But when we observe other animals on this planet, we see their sexes programmed by millions of years of evolution for different and complementary purposes. The male tends to protect the home, fend off dangers, forage for food, while the female is oriented toward the rearing of the young. And sure enough, the males in almost all of these species have much higher testosterone than the females. And the hormone is much stronger in predicting malelike behavior than chromosomes: “Species in which the female is typically more aggressive, like hyenas in female-run clans, show higher levels of testosterone among the females than among the males. Female sea snipes, which impregnate the males, and leave them to stay home and rear the young, have higher testosterone levels than their mates. Typical ‘male’ behavior, in other words, corresponds to testosterone levels, whether exhibited by chromosomal males or females.” Meerkats also have females with slightly higher testosterone than males — and guess what? — the female is more aggressive, sharing duties in foraging and hunting. I suppose you can live your life without ever fully confronting this wider natural reality, and believe that none of this has any relevance for humankind. But seriously. Open your eyes to more than your shopworn ideology.

Karkazis then argues from my exploration of testosterone that I am inferring that the hormone “provides the biological basis for male-female hierarchies.” But that’s not what I believe at all. I believe it provides the biological basis for male-female differences, not hierarchies, and hold no case for the “superiority” of one sex to another, which is to my mind, an absurd idea. I agree that social constructionism has a part to play in how we see men and women, across time and place, but I also think it’s obvious that nature also has a big say in it. That doesn’t mean restricting any opportunities for women; it means finding a way for everyone, male and female, to live the lives they want to lead. It simply means that at some point, you won’t be surprised to find differences in behavioral and social outcomes for the two sexes, and given more formal or structural political equality, as in Scandinavia, the differences in careers and lifestyles may well become starker, going forward.

Two sexes — naturally designed for difference and complementarity — are a feature of our species, not some kind of bug you want to eliminate. And trying to eliminate that difference is at some deeper level not a defense of women but an assault on humanity as a whole.

Why Democrats Are Losing Young White Men

A funny thing happened after the 2016 election: Millennials moved away from the Democrats.

Given their love of Obama and their loathing of Trump, how can this possibly be? After all, a recent poll found only 33 percent support for Trump among the young, and “the majority believe that the president is ‘mentally unfit’ (60 percent), ‘generally dishonest’ (62 percent) or ‘a racist’ (63 percent).” Pew also found a massive millennial revulsion at Trump and consolidated support for a progressive agenda.

So what to make of another huge survey — 16,000 millennial respondents — that found that they were not as hostile to the GOP as a party as they are to Trump? It also found a significant group of millennials who had not become Republican, but who had lost their Democratic affiliation. Support for the Dems went from 55 percent to 46 percent from 2016 to 2018. Home in further and look at white millennials, and the drop is 47 percent to 39, which is dead even with the 39 percent who back the Republicans.

Then look at white millennial men. They’ve gone from 48 percent to 37 percent Democratic support. More striking in their case is that they haven’t just moved away from the Democrats, but have now become Republicans. Their support for the GOP in the last two years has gone from 36 percent to 46. Which means that for white men between the ages of 18 and 34, the GOP now has a ten-point lead. It has achieved that swing in the last two years.

We don’t know why this has happened. It may be the economy, lower unemployment, and marginally lower taxes. But that doesn’t explain the yawning and growing gender gap. So here’s a guess: When the Democratic party and its mainstream spokespersons use the term “white male” as an insult, when they describe vast swathes of white men in America as “problematic,” when they call struggling, working-class white men “privileged,” when they ask in their media if it’s okay just to hate men, and white men in particular, maybe white men hear it. Maybe the outright sexism, racism, and misandry that is now regarded as inextricable from progressivism makes the young white men less likely to vote for a party that openly advocates its disdain of them.

I don’t know for sure, of course. All I know is that, to my mind, bigotry is still bigotry, whoever expresses it. And those routinely dismissed as bigots might decide to leave a party that so openly expresses its disdain for them.

See you next Friday.