Howard Schultz is the quintessential corporate Democrat. As CEO of Starbucks, Schultz preached (and, arguably practiced) the gospel of “conscious capitalism” — a creed that insists corporations can do well for their shareholders, by doing good for the world. He supports a wide variety of progressive goals that do not involve taking money away from rich people — and even endorses a few that do. His bona fides as a “woke” billionaire are so robust, Hillary Clinton had reportedly planned to make him her Labor Secretary.

On Monday, Schultz resigned from the board of his coffee company, and signaled interest in a potential run for president. The coffee magnate has left his precise intentions for 2020 unclear — but he’s made his desire to influence the Democratic Party’s internal politics unambiguous.

In recent interviews, Schultz has argued that progressive Democrats have grown so rigidly ideological, they can no longer recognize basic political and policy realities.

He has also contended that the wealthiest nation in human history can’t afford to provide public health insurance to all of its citizens; that the national debt is a bigger threat to the United States than climate change; and that Democrats would be wise to demonstrate “leadership” to the electorate — by calling for cuts to Social Security and Medicare.

“It concerns me that so many voices within the Democratic Party are going so far to the left,” Schultz told CNBC Tuesday. “I say to myself, ‘How are we going to pay for these things,’ in terms of things like single payer [and] people espousing the fact that the government is going to give everyone a job. I don’t think that’s realistic.”

Schultz went on to say, “I think the greatest threat domestically to the country is this $21 trillion debt hanging over the cloud of America and future generations … The only way we’re going to get out of that is we’ve got to grow the economy, in my view, 4 percent or greater. And then we have to go after entitlements.”

In an interview with Time magazine earlier this year, Schultz argued that any fair-minded Democrat — or Republican — would reach this same conclusion, if they only left “their ideology outside the room and recognized that we’re here to walk in the shoes of the American people.”

But there’s nothing “realistic” or “non-ideological” about Schultz’s worldview. In fact, his ideological commitments are more detached from empirical and political reality than are those of the left-wing Democrats he decries.

There is no mathematical reason why the U.S. government cannot “afford” single-payer health care. America has a higher per-capita GDP than Denmark, Canada, France, the United Kingdom, and virtually all other European and Asian nations that boast universal health insurance systems. The U.S. also has lower tax rates than most developed nations — and spends more on its military than China, Russia, Saudi Arabia, India, France, United Kingdom, and Japan combined. There is no question that America has the means to ensure that all of its residents have high-quality, affordable health care. The fact that the U.S. declines to do so is the product of political choices not technical necessities.

America does have a genuine problem with rising health-care costs. But keeping those costs off of Uncle Sam’s books doesn’t make them disappear. In fact, it likely makes them more of a problem: Single-payer systems have had a much easier time of containing costs than America’s has. (There are worthwhile arguments for the political merits of pursuing a strong public option over a rapid transition to single payer, but Schultz didn’t make one of those.)

Further, the idea that the national debt is the greatest domestic threat to the United States is nearly as indefensible. The U.S. government is not like a household or a business (although, plenty of businesses recognize the benefits of debt-financed investment) because it can print its own currency. And unlike Venezuela, our currency is backed by a vast and dynamic economy, and the largest military in world history. This makes our debt an exceptionally safe investment, in a world growing ever more crowded with savers desperate for a secure place to store their wealth. For this and other reasons, racking up $21 trillion of debt hasn’t prevented America from continuing to borrow money at near-zero interest rates. And there is little reason to expect those rates to spike rapidly at any point in the foreseeable future. Currently, America’s debt is equal to a little over 100 percent of its GDP. Japan, meanwhile, has debt equal to 250 percent of its GDP — and can still borrow money at virtually no cost.

The other downside to running high deficits is that they have the potential to fuel inflation — but after a decade of deficit-spending and accommodative monetary policy, America’s inflation rate remains below the Federal Reserve’s target. For now, our economy could use more inflation — not less — and there is no basis for believing that inflation will just start accelerating rapidly once we’ve gone too far.

In this context, it is not realistic to believe that reducing government spending should take precedence over making massive investments in a clean energy grid; it is delusional.

Finally, Schultz’s fixation on entitlement cuts betrays either an ignorance of — or callous indifference to — the bleak finances of America’s retirees. The collapse of private-sector pensions — along with the failure of wage growth to keep pace with the rising costs of health care, housing, and higher education — has left Americans more dependent on Social Security benefits for their retirements, not less: As of 2016, nearly half of U.S. families had no retirement account savings at all, according to a report from the Economic Policy Institute (EPI).

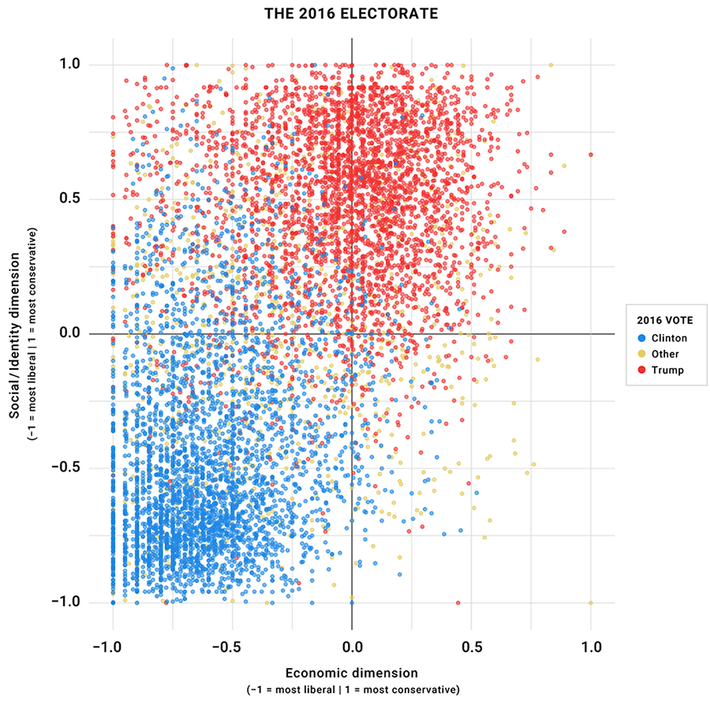

But Schultz’s radical centrism doesn’t just render him incapable of putting evidence above ideology on policy matters; it also compels him to put purity above pragmatism on the electoral front. The conscious capitalist’s combination of socially liberal beliefs (he’s pro-gun control, immigration, and gay marriage) and fiscally conservative ones (he wants to cut Medicare and Social Security) might put him at the “center” of the ideological spectrum at Davos. But those views put him on the radical fringe in the United States: According to data collected by the Voter Study Group, the percentage of the 2016 electorate that held right-of-center views on economic matters — and left-of center ones on “identity” issues — was a whopping 3.8 percent.

Now, look: Howard Schultz will never be president. The man is the embodiment of nearly everything that Democratic primary voters are anxious to vote against: A white male billionaire — with no political experience — who opposes universal health care and supports entitlement cuts.

Thus, some may reasonably feel that Schultz’s 2020 trial balloons should simply be ignored: If Democratic consultants want to sell a billionaire on a doomed, vanity campaign — that will progressively redistribute wealth from his bank account to theirs — why stand in their way?

But the trouble is that Schultz does speak for a real constituency. His ideology might not appeal to a great many voters, but the ones it does appeal to have great deal of money: There are a lot of coastal-dwelling corporate executives in the United States who want to vote for a political party that doesn’t threaten their gay friends or abortion rights; champions capital-friendly trade agreements; and recognizes deficit reduction as the political (if not moral) challenge of our time — and many of them are willing to pay for the privilege of having that party on their ballots.

To this point, the Democrats’ leading lights have shown little deference to Schultz’s faction. The Center for American Progress (the Democrats’ Establishment think tank) recently released proposals for a federal job guarantee and a universal health-care plan — while the party’s top presidential prospects in the Senate have been racing to pledge their allegiance to socialized medicine, free public college, universal child care, and paid family leave. Some of these proposals come with specified revenue sources; the majority do not. And if you try to take progressive Democrats to task for the latter fact, they’re likely to reply as Hawaii senator Brian Schatz did in a recent interview with New York: “Republicans are tactically skillful about never talking about paying for what they want, and Democrats are always very earnestly trying to satisfy the 13 people who are still doing third way work on K Street, and it’s a game that disadvantages Democrats, and I don’t want to play it anymore.”

And yet, if the Democratic Party’s wonks and 2020 hopefuls are moving sharply left on fiscal issues, its House caucus remains home to no small number of “Blue Dogs,” and “problem-solvers” who evince sympathy for “third way” verities. And given the fact that winning elections in the United States isn’t getting any less expensive, it would be unwise to assume that Howard Schultz’s point of view has become politically irrelevant, simply because it has grown intellectually unfashionable.

Progressives can’t get complacent: They must force the Democratic Party to distance itself from radical centrists like Schultz, whose divisive rhetoric — and fringe ideology — threatens to condemn America to another four years of Trump.