One of the oddest aspects of Donald Trump’s political persona is that it is simultaneously populist and nakedly disdainful of ordinary people. The president speaks more colloquially — and derides “elites” and “the Establishment” more bitterly — than any of his modern predecessors. And yet, he is also a more unapologetic advocate for hierarchy — and the submission of the weak to the strong — than any democratic leader in recent memory.

Trump’s entire career is built on an implicit contempt for ordinary Americans. His businesses (reportedly) routinely defrauded their customers, stole wages from their contractors, and fleeced their small investors. His political rhetoric is so shamelessly mendacious, it evinces an implicit doubt in his own voters’ capacity for rational thought.

But plenty of politicians betray an unspoken disrespect for their constituents. What makes Trump’s elitism so remarkable is that it is often explicit: This is a president who defended his decision to staff his Cabinet almost exclusively with multimillionaires by saying, “I just don’t want a poor person” to be “in charge of the economy.” Before that, he was a “populist” politician who referred to blue-collar workers as “the poorly educated”; boasted that his base would mindlessly support him even if he committed first-degree murder in broad daylight; and regularly informed voters that many of the things he’d been saying for months were actually insincere, and were intended solely to manipulate them.

This week, Trump finally gave his contempt for the “forgotten man and woman” cinematic expression — in the form of a trailer for a fake, buddy-adventure movie starring himself and North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un.

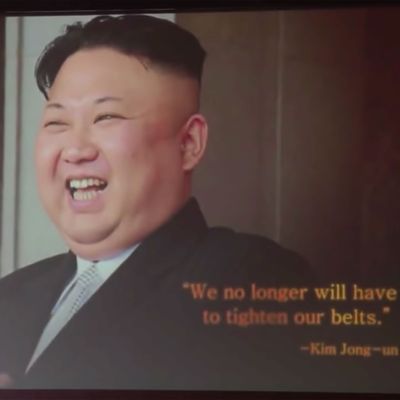

When this film first began playing for reporters at the summit in Singapore Tuesday, most assumed that it was North Korean propaganda. And it isn’t hard to see why: The trailer portrays Kim as a world-historic hero who is on the cusp of leading his nation into a bright and beautiful tomorrow — one where they will enjoy unprecedented prosperity, and a long-lost harmony with their neighbors in the South.

The fact that the White House National Security Council produced this warm portrayal of a homicidal tyrant — whose regime subjects political prisoners to rape and starvation in a vast network of gulags, imposes forced abortions on women who become pregnant by non-Korean men, and condemns practicing Christians to indefinite imprisonment — has inspired no small amount of outraged incredulity: It is one thing to dignify a fascist dictator with a face-to-face meeting, for the sake of advancing a vital national security interest; it is another to make a movie that explicitly argues the North Korean people could be well served by that dictator’s reign extending indefinitely into the future.

But the film is not just callously indifferent to the oppression of ordinary North Koreans; it is also disdainful of ordinary Americans.

“Seven billion people inhabit planet Earth,” a voice-over announces at the trailer’s opening. “Of those alive today, only a small number will leave a lasting impact. And only the very few will make decisions or take actions that renew their homeland and change the course of history.”

One can make an argument for the trailer’s virtues as a diplomatic tool. To the extent that North Korea can be convinced to denuclearize, they must be reassured of their regime’s long-term security. Kim is a film enthusiast; Trump is used to making real-estate pitches that seduce viewers with images of gorgeous landscapes and shiny new construction. The White House needed some means of conveying its message across the vast cultural divide between the two rulers. One can imagine worse gambits than the one they came up with.

But the film’s opening suggestion that the destinies of both the United States and North Korea lie in the hands of two great men of history — while each nation’s ordinary citizens pass through the world without leaving a lasting mark — cannot be justified on diplomatic grounds. There were plenty of ways for the voice-over to establish the historical importance of the Singapore summit, or the immense responsibility that Trump and Kim share for their nations’ futures, without declaring that most of the Earth’s 7 billion humans will never do anything of real importance; as though the schoolteacher who cultivates her students’ love of learning, the working mom whose selfless devotion to her children keeps them well-fed and well-loved — or the steel workers whose toil provides the literal backbone of Trump’s great towers — have made “no lasting impact” on our world.

Instead, the film posits an inherent kinship between Trump and Kim — as members of that tiny elite that managed to rise above the ephemeral hordes, and achieve historic relevance.

Which makes sense.

To the extent that Trump and Kim have any shared values, they are ones that derive from a faith in the inherent justice of established hierarchies. For Trump, power is synonymous with virtue — which makes authoritarian rulers inherently virtuous. In Singapore, Trump spoke admiringly of the “talent” Kim displayed in inheriting absolute rule over his nation when he was only 26, and then consolidating that rule with violence: “Anybody that takes over a situation like he did at 26 years of age, and is able to run it and run it tough — I don’t say it was nice or I don’t say anything about it … very few very few people at that age, you can take one out of 10,000 probably couldn’t do it.”

Trump has expressed admiration for the power and ruthlessness of a long list of authoritarian dictators. During the 2016 primary, he argued that the Chinese government had shown great “strength” when it “kept down the riot” at Tiananmen Square. Twenty-six years earlier, he had told Playboy that the American government could gain more international respect if it would only emulate China’s display of toughness in Tiananmen.

In that same 1990 interview, Trump spelled out the Social Darwinist subtext that seethes beneath his words and deeds. “The coal miner gets black-lung disease, his son gets it, then his son,” the real-estate heir explained. “If I had been the son of a coal miner, I would have left the damn mines. But most people don’t have the imagination — or whatever — to leave their mine. They don’t have ‘it’ … You’re either born with it or you’re not.”

It is hard to reconcile this worldview with reverence for democracy. If common Americans are, by definition, those who lack the imagination and vitality of the elite, why on Earth should the former collectively rule over the latter?

In its cinematic gift to Kim Jong-un, the White House produced a utopian vision of progress and national flourishing — in which ordinary North Koreans were not agents of their own destiny, but only the passive beneficiaries of a great man’s beneficent wisdom.

This vision may be outrageous for the way it endorses authoritarian rule in North Korea; but it is more unsettling for the way it intimates a desire to bring such rule back home.