In 1989, then-Senator Joe Biden went on TV to criticize President George H.W. Bush’s National Drug Control Strategy. Bush was seeking to accelerate the War on Drugs by pumping over $1 billion into narcotics-related law enforcement, expanding the resources available to prosecutors, jails, and prisons, and harshening punishments for drug dealers. Biden argued that the president was not going far enough. “Quite frankly, the president’s plan is not tough enough, bold enough or imaginative enough to meet the crisis at hand,” he said, responding to Bush’s speech outlining the plan that September. “[It] does not include enough police officers to catch the violent thugs, enough prosecutors to convict them, enough judges to sentence them, or enough prison cells to put them away for a long time.”

Nearly 30 years later, Biden is an early front-runner for the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination. His party on Tuesday voted unanimously to pass the First Step Act through the Senate, partnering with all but 12 Senate Republicans to secure the biggest changes to the federal criminal-justice system in years. The most vocal of the 12 holdouts was Senator Tom Cotton, a “tough on crime” Arkansan who has made a habit of opposing reform using language strikingly similar to Senator Biden’s. “If anything, we have an under-incarceration problem,” Cotton said in a 2016 speech at the Hudson Institute. Earlier this month, he castigated the First Step Act as “criminal leniency legislation.”

Separated by three decades and a partisan gap that only seems to widen by the day, Senators Biden and Cotton nevertheless illustrate how interchangeable Democrats and Republicans have traditionally been on criminal-justice policy. When they were not busy one-upping each other to prove who could be more punitive, the parties have built strong bipartisan alliances atop the shared goal of locking people in cages, especially black people.

The direction of this bipartisanship temporarily reversed this week with the First Step Act vote. Instead of worsening America’s mass incarceration crisis, Senators opted to make the experience of federal prison slightly less painful for inmates — shortening mandatory-minimum sentences for some crimes and strengthening avenues for some incarcerated people to abbreviate their prison stints. But after decades spent normalizing the existence of the world’s largest concentration of prisoners, the Overton window regarding what substantive change in the United States actually looks like has shifted so far that even modest changes seem bold and ambitious. And even that assessment is generous: The jubilation and back-patting that has greeted Tuesday’s Senate vote better reflects relief that interparty consensus is possible under President Donald Trump than the bill’s actual scope and impact.

The limitations of the First Step Act are obvious on even a cursory glance. The American federal prison and jail populations — which the bill addresses — constitute a combined 10 percent of the country’s total incarcerated population, the bulk of which is housed in local jails and, especially, state prisons. That means just a fragment of the nation’s 181,000 federal inmates would be eligible for the bill’s already-modest provisions — for example, the broader use of halfway houses and home confinement as alternatives to correctional facilities, and the availability of work and education programs inmates can enroll in to earn “time credits” toward early release. The lives of the roughly 2 million prisoners locked up locally or at the state level will go unaltered. Even some of the bill’s more galvanizing provisions — though undeniably meaningful for the several thousand men and women they would affect — are more akin to making good on already existing policy than dramatic overhauls. The punishment disparities for crimes involving crack and powder cocaine that the First Step Act addresses had already been narrowed with the Fair Sentencing Act in 2010, though Tuesday’s bill would make its provisions retroactive. The bill also bans the shackling of pregnant inmates — which has been banned for a decade, since 2008.

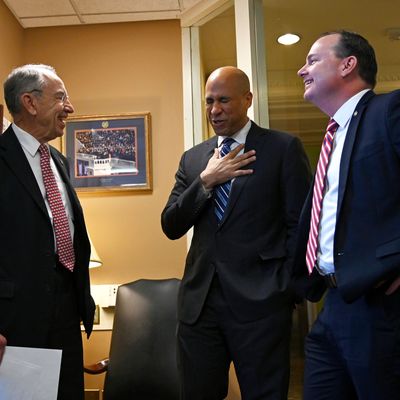

These are not meaningless steps, to be sure. But the bill’s reach is inconsistent with the celebration that has greeted its passage in the Senate. The hero image of the New York Times story on the subject shows Democratic senator Cory Booker of New Jersey embracing Chuck Grassley, the Iowa Republican who played his party’s most dogged role in advancing the bill through Congress. “This is literally one of the reasons I came to the United States Senate, to get something like this done,” Booker said, according to the Times. “This is the biggest thing,” Grassley said after the vote. “Except maybe getting a Supreme Court justice.” Today’s reform ideas gained traction in the Obama era, when a spate of police killings invigorated a national debate about the criminal-justice system’s excesses. “[The] African American community got more insistent in its claims, and the Republicans got more reasonable in their own critique and set of concerns about criminal justice,” activist and former-Obama adviser Van Jones told the Guardian. That it took years of wrangling and negotiation to secure a compromised echo of an already-modest reform bill Republicans killed in 2016 bodes poorly for the future improvements — which many senators already acknowledge are necessary. “The First Step Act takes modest but important steps to remedy some of the most troubling injustices within our sentencing laws and our prison system,” Democratic senator Patrick Leahy of Vermont said, according to the Washington Post. “It is my hope that this bill represents not just a single piece of legislation, but a turning point in how Congress views its role in advancing criminal justice.”

Indeed, the First Step Act is seen by many as just that: step one toward what reformers hope are more sweeping overhauls to come. But no second step is promised. And the traits that make the bill seem like a political no-brainer — namely, that so many senators seem to agree about its necessity across party lines — are also traits that invite skepticism regarding its impact and durability. Revolution is not fomented in the gap between Ted Cruz and Joe Manchin on the ideology spectrum. The overhauls needed to actually reverse American mass incarceration are far less broadly palatable than what the current bill proposes. The Act’s provisions and corresponding rhetoric reserve most of their generosity for drug offenders, many of them nonviolent, who constitute almost half of the federal prison population. But limiting leniency to people convicted of nonviolent crimes — unless you, like Tom Cotton, believe that selling cocaine is a violent crime — does nothing for the 54 percent of state inmates who are incarcerated for acts of violence. Solving a 2.2 million-person problem is impossible if you view nearly a million of them as untouchable — especially when even officials who backed the bill deny more significant changes to the system are needed. “I don’t think our justice system is fundamentally broken, unjust, or corrupt,” First Step Act co-sponsor and Republican senator Mike Lee of Utah wrote for the National Review in November. “I know from experience that dangerous criminals exist — individuals who are incapable of or uninterested in rehabilitation and change.”

Considering how joyously the bill’s passage was received on Capitol Hill this week, Lee’s insinuation that fundamental change is unnecessary may seem a minor smudge on an otherwise triumphal narrative. In reality, it lays bare what a fragile foundation the First Step Act actually rests on. Partisan rancor made its passage seem unlikely. But the same fears, biases, and political considerations that rendered it relatively toothless threaten to undermine whatever incremental gains secured. The American electorate is far from immune to strongman politics or fear-mongering around crime — the election of Donald Trump confirmed that. “Law and order” crackdowns have historically transcended partisan differences, uniting presidential administrations from Lyndon Johnson’s to Ronald Reagan’s and Bill Clinton’s. The trip from Joe Biden to Tom Cotton is perilously short. It only takes one crisis, or shift in public opinion, to drive America back into mass incarceration’s heyday.