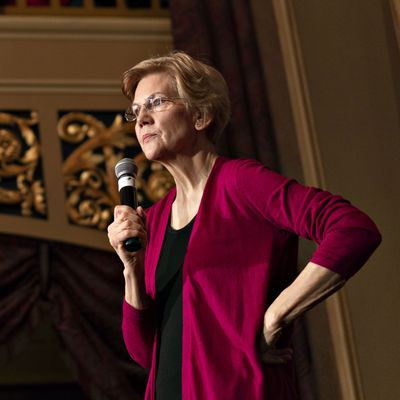

Last September, I wrote about Elizabeth Warren’s smart platform, which has harnessed the most politically attractive elements of the populist agenda while avoiding the most politically vulnerable parts. The concerns I have about Warren as a policymaker are not the issues she talks about, but the issues she doesn’t. Here are two issues where I believe Warren has done the wrong thing. There is a common theme here: They challenge and complicate her populist appeal.

The medical device tax. When Democrats wrote the Affordable Care Act, they paid for it in part by cutting back payments to medical providers. The logic was that, since the government was going to create tens of millions of new paying customers, the industry that would profit from serving those customers could contribute some of its windfall to financing their care and still come out even. Doctors, hospitals, pharmaceutical companies, and insurers all accepted this bargain, but the one sector that refused was the medical device industry. So rather than let the medical device industry get away with being the one sector that enjoyed the profit from a coverage expansion without bearing any of the cost, lawmakers imposed a 2.3 percent tax on medical devices.

The industry has relentlessly lobbied to repeal the tax. Massachusetts contains a major hub of medical device manufacturing, and Warren has relentlessly championed her home-state interest. She has co-sponsored legislation to repeal the medical device tax, written an op-ed advocating the tax repeal for the industry’s own newsletter, and proposed a bill that would penalize manufacturers of pharmaceuticals (but, crucially, not the medical device industry) for misappropriating funds intended for scientific research.

Education reform. There may be no state in America that can more clearly showcase the clear success of charter schools than Warren’s home state of Massachusetts. Professors Sarah Cohodes and Susan Dynarski conducted a study proving the massive gains produced by charter school students in the Bay State. Because Massachusetts has a cap on the number of students allowed to attend charters, its students have to enter a lottery to apply. This allowed Cohodes and Dynarski to compare the performance of students who won the lottery with those who lost, a perfectly randomized sample, across a broad suite of metrics. The students who won the lottery and attended a charter outperformed the lottery losers in every way: state test scores, SAT scores, number of advanced placement classes and test scores in those classes, and college attendance. (Three-fifths of the lottery winners went on to attend a four-year college, compared to only two-fifths of the lottery losers.) The gains were equally large or larger for low-income students, students who entered school with low test scores, special-education students, and English-language learners.

The charter sector would like to admit more students in Massachusetts, but the state has a cap preventing more students from enrolling. A state referendum in 2016 proposed to increase the cap so that more low-income urban students can enroll in a charter school. The state’s teachers union fiercely opposed the measure, and spent millions of dollars to defeat it. Unions oppose charters in large part because charters have largely nonunionized contracts, which allows them to fire ineffective teachers, something that is extremely difficult to do in a traditional public school with a union contract.

Warren opposed Question 2, which was defeated in November in a vote that crushed the chance for thousands of low-income urban students in Massachusetts to have a chance at a great education and a future in college. Given this position, it is fair to infer that she would support the teachers union on any position, however harmful it might be to the well-being of low-income students.

***

Neither of these positions is likely to harm Warren’s chances of becoming president. Just the opposite: They are relatively low-profile issues where a well-organized interest group cares a lot about the outcome, and most people don’t know anything about the issue at all.

My concern, rather, is what these issues tell us about Warren as a policymaker. She has done an effective job of mobilizing public opinion against the finance industry, which has had a nefarious impact on public policy. But presidents have to deal with all the issues, and many of them have organized lobbyists defending terrible policies that fly under the radar. There’s no such thing as a perfectly pure politician, of course. But from my standpoint, medical-device-tax repeal and the Massachusetts charter cap are especially unjustifiable policies, which makes her stances on these issues especially discouraging.

And then there is the question of Warren’s political profile. For better and for worse, she is a moralist. This allows her to communicate sometimes complex issues in simple and clear terms, and thus to bring public pressure to bear on issues that are usually confined to smoke-filled rooms. But it also leaves her lacking in a language to explain the issues where she doesn’t have a clear people-versus-the-powerful frame.

And on a presidential campaign, you lose the ability to pick and choose the issues you talk about. You have to talk about whatever issues come up. Some of them will be issues where the merits of Warren’s stance are morally ambiguous, or worse. Her great advantage, and the quality that I think makes her a formidable contender, is that she has built a brand based on moral clarity. The campaign will test what happens when she is faced with situations that tarnish it.

Update, January 15, 2019: Ben Mathis-Lilley in Slate raises several objections to my criticism of Warren’s opposition to raising the charter cap. The first is a quibble, and the others are outright wrong. The quibble is that Mathis-Lilley objects to my description of teachers unions as “powerful” in the headline. Later in the article, I expanded slightly, calling her opposition to charter expansion a case “where a well-organized interest group” — i.e., the union — “cares a lot about the outcome, and most people don’t know anything about the issue at all.” Mathis-Lilley notes that many millionaires support education reform, and even donated to support Question 2.

That’s true! However, it’s not terribly relevant to my point, which is that the interest group that has power over Warren here is the teachers union. Teachers unions are an extremely well-organized faction within the Democratic Party, accounting for a wildly outsize share of its activists and delegates, and Warren has a strong incentive to stay on their good side. Indeed, many supporters of teachers unions frequently make triumphalist assertions that they will soon make support for education reform totally untenable within the Democratic Party. Just as it’s hard for Warren to evaluate the merits of the medical device tax when the industry has such a heavy footprint in her state, it’s hard for her to focus solely on the well-being of urban students in Massachusetts when doing so could end her presidential ambitions. That’s the kind of power I am describing.

Mathis-Lilley also asserts my wife “works in charter school advocacy” and chides me for failing to disclose that in my story. In fact, my wife works for an education research organization and is not engaged in advocacy. My wife is a strong personal supporter of education reform, but that is not her job

— neither my wife nor her employer attempt to persuade policymakers, voters, or anybody else to expand their charter sector.

Mathis-Lilley makes two arguments in defense of Warren’s position. First, he writes, “even Dynarski and Cohodes’ executive summary in the Brookings paper cautions that their data show that ‘the effects of charters in the suburbs and rural areas of Massachusetts are not positive.’” But the fact that Massachusetts charters are highly effective in urban areas, and ineffective elsewhere, is not a concession they quietly admit. It’s the main point, which they repeat clearly because it underscores their entire argument.

I wrote about this two years ago: “As the authors note, non-urban charters don’t yield better outcomes. It is only the urban charters that are producing these kinds of improvements.” Mathis-Lilley was totally nonplussed then, too. My recent follow-up does not do as good a job as the original piece of clearly delineating that the entire policy focus centers on urban charters, not the less-effective suburban ones, but it’s the premise of the entire dispute. Massachusetts has a cap that allows more students to enroll in charters in suburban areas (which are no more effective than traditional schools), while preventing new enrollees in the cities (where charters are far more effective). That was the rationale for Question 2, which would have lifted the cap only in the urban areas. Dynarski and Cohodes wrote, “Massachusetts’ charter cap currently prevents expansion in precisely the urban areas where charter schools are doing their best work.”

Mathis-Lilley now somehow treats the fact that charters are only highly effective in urban areas as a point against allowing more children to enroll only in urban charters. That’s bizarre. He’s repeating the evidence in favor of Question 2 as if it’s evidence against it.

Mathis-Lilley goes on to make a serious (and unfounded) attack on Cohodes and Dynarski. He asserts that their studies do not even prove that urban charter schools in Massachusetts do a better job of educating children. He seizes on the fact that they do not study charter schools that closed:

If you look at the methodology of the 2013 and 2016 studies, you find that the studies didn’t even cover every charter school in Boston … The 2013 study had the same limitation: Its central analysis (comparing the winners and losers of charter school enrollment lotteries) didn’t include data from schools that were closed or that didn’t keep “adequate” records. The 2013 study did note that those schools appeared to be “poor academic performers.”

According to Mathis-Lilley, this omission “does suggest that the Dynarski-Cohodes data do not conclusively prove one way or the other that charters in general have in fact been a net positive for Massachusetts students.”

Again, the issue is urban students, but never mind that. Mathis-Lilley is making a serious accusation. He’s charging that, by omitting bad charters, they slanted their sample and produced an invalid response. On Twitter he accused them of “misleading characterizations of the scope of their studies in their Brookings paper, which I don’t believe mentioned that charters which closed or were disorganized weren’t studied.”

Cohodes wrote a long Twitter thread explaining why he’s wrong. It’s a little complex, but in short: No, they didn’t commit an amateurish error that invalidates their entire paper. Their main data set was the lottery system. One difficulty of studying the effects of charters is that students whose parents go to the effort of enrolling them in a charter might be different than students whose parents don’t, even if you try to control for traits like test scores. The value of a lottery is that all the kids in it are the same. Therefore, you can compare the winners (who got accepted into charters) with the losers.

Of course, this means you can only study charter schools that hold lotteries. Which, in turn, means you can only study charter schools that have more applicants than available spots. (If you have enough sports for every applicant, you don’t need a lottery.) Now, does this change the finding? No, explains Cohodes. And the reason is that oversubscribed charters (which hold lotteries) account for the overwhelming majority of students in the system:

Other kinds of studies that don’t rely on lottery comparison, and which do study the entire charter sector find the same effect — that urban charters in Massachusetts produce large gains. So Mathis-Lilley’s objection is wrong. Dynarski and Cohodes did think of this problem, and it does not change their underlying conclusion about urban charters in Massachusetts.

Of course, Mathis-Lilley is entitled to believe that the structure of charter schools in general is offensive to his values, or that strong labor protections for teachers matter more than good educations for urban children. But denying that urban charters in Massachusetts do teach children more effectively is not tenable.