Billionaire coffee-shop mogul Howard Schultz is seriously thinking of running for president as an independent. Schultz appears to be one of those rich people who has confused his success in one field with a general expertise in every other field that interests him. His apparently sincere belief that he can be elected president is the product of a sincere civic-minded commitment to the public good and an almost comic failure to grasp how he might accomplish this. That confusion is probably being spread by his hired staffers, whose financial incentive, conscious or otherwise, is to encourage him to embark on a costly political fiasco.

We shouldn’t feel too bad if Schultz wants to waste some of his great-great-grandchildren’s inheritance playing political fantasy camp. The problem is that Schultz’s earnest confusion might succeed just well enough to have catastrophic consequences.

Schultz initially contemplated entering the Democratic primary, correctly calculated that he stood no chance of success that way, and then incorrectly decided that he could win as an independent. His public comments reveal how little he grasps about American politics.

The independent label is a myth. Schultz believes that the large cohort of Americans who identify as “independents” indicates a market for a centrist candidate positioned between the two parties. “What we know, factually, is that over 40 percent of the electorate is either a registered Independent or currently affiliates themselves as an Independent,” he says, “Because the American people are exhausted. Their trust has been broken. And they are looking for a better choice.”

That is not factual. In reality, while some voters are true independents who swing between both parties, political scientists have shown conclusively that most self-identified independents are closet partisans. They lean toward one party or the other, and they vote for that party more consistently than self-identified members of that party. The growth of the “independent” label reflects changing social mores, and the fashionability of calling yourself independent indicates an independence of thought. This is why the increase in independent self-identification has coincided with a broad decline in swing-voting and split-ticket voting.

The electorate is polarized around Trump. When asked the obvious question about the effect of his candidacy — “Do you worry that you’re going to siphon votes away from the Democrats and, thereby, ensure that President Trump has a second term?” — Schultz gave a nonresponse:

I wanna see the American people win. I wanna see America win. I don’t care if you’re a Democrat, Independent, Libertarian, Republican. Bring me your ideas. And I will be an independent person, who will embrace those ideas. Because I am not, in any way, in bed with a party.

The reality is that a Schultz candidacy probably would draw more support from the Democrats than from Trump. Schultz has liberal views on a wide array of social issues, like immigration, gay rights, and racial justice. These cultural issues form the main basis for the polarization of the electorate. To the extent that anything has scrambled the culture-war polarization, it is Trump’s lightning-rod personality.

But this fact simply underscores the degree to which anybody who isn’t Trump simply divides the anti-Trump vote. Even conservative Republicans like John McCain and John Kasich saw their support soar among Democrats, and plummet among Republicans, because they positioned themselves in opposition to Trump. The dominant issue in American politics in 2020 is going to be Trump, and even a relatively conservative splinter candidate will tend to draw from the anti-Trump side.

The center is not what Schultz thinks it is. “Republicans and Democrats alike — who no longer see themselves as part of the far extreme of the far right and the far left — are looking for a home,” he tells the New York Times. What would this center look like? In Schultz’s mind, it would combine his social liberalism with a desire to cut social insurance programs. “We can get the 4 percent growth,” he said last year, “we can go after entitlements, and we can do the right thing — if we have the right people in place.”

In reality, there is no constituency for cutting these programs in either party. A 2017 Pew survey found 15 percent of Republicans, and 5 percent of Democrats support cuts to Medicare, while 10 percent of Republicans and 3 percent of Democrats support cuts to Social Security.

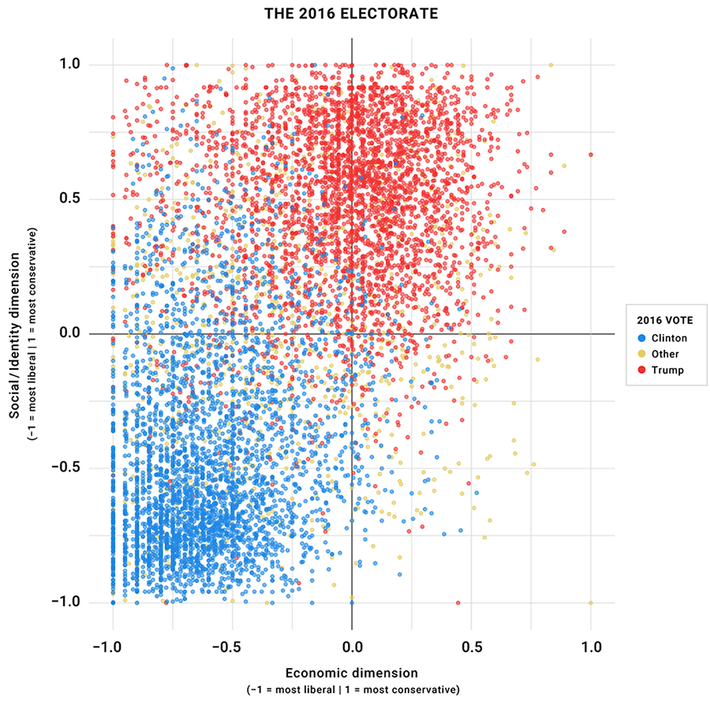

A survey of the 2016 electorate by the Democracy Fund Voter Study Group

plotted voters by social and economic views. What it found is that many voters have socially conservative and fiscally liberal views — those are the voters who were attracted to Trump’s combination of nativism and promises to maintain social programs and provide universal health care. Vanishingly few voters have socially liberal and fiscally conservative beliefs:

There is a center in American politics, but it’s the opposite of what Schultz imagines.

Democrats haven’t moved far left yet. Having conjured an imaginary center that happens to match his own views, Schultz rationalizes his candidacy by insisting that Democrats have moved away from it. “If you have a choice between President Trump and a far-left progressive Democrat,” he says, “many people think President Trump will get re-elected.”

In theory, it is possible to imagine the Democratic nominee adopting a bunch of unpopular left-wing policies. Schultz lists what he imagines these to be: “When I hear people espousing free government-paid college, free government-paid health care and a free government job for everyone — on top of a $21 trillion debt — the question is, how are we paying for all this and not bankrupting the country?”

The trouble with his argument is that these are neither policies the Democratic Party has adopted, nor are they unpopular. Democrats have debated all of these concepts, and they have made some headway because they poll well, at least in the abstract. Free college is popular. “Free government-paid health care” is exactly what Trump promised when he was elected, and a job guarantee also polls well.

But most Democratic politicians also understand that all of these plans have significant trade-offs or implementation problems, which is why most candidates have either refrained from committing themselves to a specific program or proposed more modest versions. For instance, Elizabeth Warren is promising a “debt-free option,” which is a far more limited proposal than “free college.” Candidates like Cory Booker have endorsed small-scale demonstration projections for a job guarantee, but nobody is proposing a national version because nobody has figured out how to design a workable plan yet. Most Democrats are signaling their desire to make incremental advances on health care, via a Medicare buy-in and a public option, rather than the full single-payer proposal supported by Bernie Sanders.

For a person who considered running as a Democrat, and whose views on Democratic politics have played an instrumental role in his decision, Schultz seems to have shockingly little understanding of the state of the policy debate within the Democratic Party.

There’s a huge difference between the parties on the deficit. Schultz’s complaint with the Democratic Party revolves primarily around the long-term debt. But while Democrats do not share his wildly unpopular belief in cutting retirement programs, they also don’t have the wildly profligate fiscal policy that has become de rigueur in the GOP. Indeed, many Democratic candidates are proposing substantial new revenue increases (most recently, Elizabeth Warren’s call for a wealth tax).

Obviously, deficit reduction is politically difficult. It’s easier to propose ideas to reduce the deficit when you’re not trying to get people to vote for you. In this context, Schultz’s answer to a question about the Trump tax cut was revealing:

I would not have given a free ride to business, from 35 percent or 37 percent to 21 percent. It would’ve been more modest. But I would’ve significantly addressed the people who need tax relief the most, which is the people I talked about earlier, who don’t have $400 in the bank.

Schultz is being asked about a highly unpopular Trump administration policy that increased the deficit by $2 trillion. This is the closest thing to a layup he can get. But Schultz can’t even bring himself to pose as a deficit hawk on this specific issue. Instead, he says he would have scaled back the tax cut for the rich a little, and spent the savings on a big tax cut for the middle class. If Schultz can’t hold himself to the easiest possible anti-debt stance on his very first day as a political candidate, you have to wonder about his claim that he can find the political courage on this issue that the entire Democratic Party is allegedly lacking.

The explanation for his confidence is surely Schultz’s belief that whatever skills enabled him to sell a lot of coffee would somehow translate into mastering a political system he barely understands. History sometimes hinges on small contingencies. It is entirely possible that the course of American history will turn on Howard Schultz’s egomaniacal ignorance.