As we barrel toward the next season of presidential primaries and caucuses (on the Democratic side, at least), it’s normal to think about the successful campaigns of the past that set a template for today’s POTUS wannabes. Some classics are easy on the memory, like come-from-nowhere nomination winners George McGovern in 1972, Jimmy Carter in 1976, and, yes, Donald Trump in 2016, as are such strategic masterpieces as Barack Obama’s campaign and John McCain’s back-from-the-dead effort in 2008.

But with what will ultimately be dozens of candidates running for the next Democratic nomination, there will be a lot of losers who follow very different precedents — the types of campaigns that begin preposterously or proceed disastrously and end in the sad silence of nobody caring enough to witness the good-bye. So it’s a good time to remember the really bad nomination campaigns in both parties over the decades and consider the lessons each might offer the campaign class of 2020.

This list excludes the multitude of obscure candidates who never raised enough hopes to be worthy of being dashed but includes themes of failure that have repeated across more than one cycle, as well as 2020 takeaways where appropriate. (And please note that even bad campaigns can involve talented, hard-working people who sometimes go on to successful political careers.)

The Early Flameouts

10. Scott Walker ’16, and 9. Tim Pawlenty ’12

Both of these candidates were on-paper heavyweights thought to be exceptionally well positioned to win the nomination or at least seriously contend. Both were from states bordering Iowa. Both had serious conservative Evangelical street cred and estimable (from a conservative point of view) records as governors. And unfortunately for them, both had charisma deficits.

Tim “T-Paw” Pawlenty staked everything on winning the August 2011 Ames straw poll, then the key pre-caucus test of strength in Iowa. He finished third, well behind fellow Minnesotan Michele Bachmann, and with his money depleted, he almost immediately dropped out. Scott Walker’s campaign also foundered early, as CNN reported in September 2015:

Walker rocketed to the front of the GOP pack in Iowa after a rousing speech at the Iowa Freedom Summit in January — and subsequently, his campaign pinned its hopes on the first state to vote in the presidential nominating process.

But Walker was hurt by lackluster performances in the first two Republican debates. And his poll numbers suffered: In a CNN/ORC poll released Sunday, Walker failed to garner even one-half of 1% nationally among likely GOP primary voters.

When he withdrew, Walker called on conservatives to quickly winnow the large 2016 field so “that the voters can focus on a limited number of candidates who can offer a positive, conservative alternative to the current front-runner,” Donald Trump. That didn’t work, either.

Both Pawlenty and Walker lost gubernatorial races in 2018.

The Self-Inflicted Wounds

8. Gary Hart ’88

To some extent, all capsized campaigns can be blamed on the mistakes of their captains. But sometimes candidates self-immolate with breathtaking speed and irreversible damage. The classic of this genre was provided by Democratic candidate Gary Hart in 1987. Hart entered the 1988 cycle as a clear front-runner after nearly upsetting Walter Mondale in the 1984 primaries. He then quickly self-destructed, answering questions about long-rumored womanizing by issuing a “follow me around” taunt to reporters — which led directly to the exposure of a dalliance with a young former beauty queen named Donna Rice, including photos of Rice sitting on his lap aboard a lobbyist-piloted yacht appropriately named Monkey Business. Hart was forced from the race almost instantly, though he did reenter the field later as a forlorn, substance-focused debate contender with no real prospects.

7. Rick Perry ’12

Former Texas governor Rick Perry took longer to blow himself up. He entered the 2012 contest late but initially looked like a king-hell fireball, dispensing red meat to thrilled conservative audiences and racing to a lead in the polls. Then the debates arrived, and in one Perry stubbornly refused to follow Mitt Romney in attacking generous treatment of Dreamers, and in another turned into Bobo the Simple-Minded, unable to remember which federal agencies he had proposed to eliminate. He hung around, bleeding support, and soon after a fifth-place finish in Iowa, dropped out.

Other candidates have inexplicably damaged themselves in less-enduring ways. One good example is Democrat Ted Kennedy, who on the eve of his challenge to incumbent Jimmy Carter in 1980 granted an interview to CBS’s Roger Mudd in which he was shockingly incoherent, creating doubts about his once-indomitable political strength. Another is Republican George Romney, whose 1968 nomination campaign lost steam and expired after he attributed an abandoned position on the Vietnam War to a “brainwashing” he had received from military brass. Eugene McCarthy, alluding to Romney’s reputation as not terribly deep, supposedly quipped, “I would have thought a light rinse would have sufficed.”

There’s no telling which 2020 candidate might be susceptible to self-sabotage; by definition, it can strike candidates from a clear blue sky.

The Risk of Negative Momentum

6. Joe Lieberman ’04

Battening on the name ID he built as Democratic vice-presidential nominee in 2000, Joe Lieberman led the 2004 field in the polls for some time. But being crosswise with Democratic activists over his robust and unrepentant support for the Iraq War, Lieberman skipped Iowa and then became an object of enduring ridicule for trying to spin a fifth-place finish in New Hampshire as a sign of “Joementum.” He dropped out of the race a week later and, in the next presidential cycle, backed Republican John McCain.

Other candidates who looked solid until voters started voting and then quickly lost ground include Democrat Ed Muskie in 1972 and Republican Rudy Giuliani in 2008.

The 2020 candidate who might be susceptible to this malady, if only because his early polling is more robust than his record might suggest, is Joe Biden. He should definitely avoid claiming “Joementum.”

The Path From Ridicule to Abyss

5. Dan Quayle ’00

Quayle could fit into any number of categories of campaign-trail failure, and for that reason he deserves his own slot on the list. He was elected vice-president in 1988 after a campaign in which he was thoroughly humiliated by Democratic counterpart Lloyd Bentsen in a debate. His reputation as something of a lightweight was burnished by his most-high-profile moment as vice-president: a quarrel with fictional sit-com character Murphy Brown over her decision to give birth to a child out of wedlock (a decision that could have just as easily been reconciled with Quayle’s pro-life point of view).

His presidential campaign in the 2000 cycle went nowhere fast despite high name ID, mainly because of the persistently low regard in which he was held by voters, as Gallup’s Frank Newport explained later:

Quayle has long suffered from image problems, with unfavorable ratings that rose to 48% and 59% in the summer of 1992 when he was being chosen again to run with George H.W. Bush (at the time, it should be noted, the senior Bush’s own job approval ratings were at the low point of his administration). Additionally, Gallup polling in the summer of 1992 showed that almost four out of ten Republicans thought President Bush should dump Quayle in favor of someone else. Quayle, of course, stayed on the ticket and the Republicans lost the November election to Bill Clinton and Al Gore.

The former veep finished eighth in the 1999 Ames straw poll, trailing such political powerhouses as Alan Keyes, and soon dropped out.

There is a former veep in the field in 2020, but even among detractors, Joe Biden has inspired much more respect, and commanded much more popularity, than Quayle could ever muster. His top-ten standing is pretty safe.

The Legends in Their Own Minds

4. Wilbur Mills ’72

One of the recurring incidents of tragicomedy in presidential primaries is when puffed-up potentates of Beltway politics get confused and assume their titanic qualities will translate well in a national campaign. Representative Wilbur Mills of Arkansas was a much-revered figure in Washington as longtime chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, where, as the New York Times put it, he was “held in awe for his near-absolute sway over any legislation with fiscal consequences.” He let himself get flattered into a 1972 presidential candidacy, but after finishing a poor fourth among five candidates in New Hampshire (trailing even eccentric L.A. mayor Sam Yorty), Mills disappeared from the campaign trail. A couple of years later, Mills’s fall from grace culminated in an early-morning incident when he was found in the company of a stripper named Fanne Fox, who tried to flee the scene by jumping into Washington’s Tidal Basin.

3. Phil Gramm ’96

Phil Gramm was a Texas Democrat turned Republican senator who became a big deal in conservative circles during the Reagan, Bush 41, and early Clinton years. As RealClearPolitics explains in its own list of terrible candidates, Gramm got off to a roaring start with fundraising in the ’96 cycle but never got rolling with voters:

Despite his fundraising prowess, his national profile, and solid early poll numbers, he peaked too early. Vast sums of money were raised, but vast sums were spent, too, and on dubious goals, such as winning non-binding straw votes in states of little strategic importance.

The first contest in 1996 came February 6 in Louisiana, which sought to usurp Iowa and New Hampshire that year. His mere participation in Louisiana hurt Gramm among the Republican establishment in Iowa, which jealously guards its first-in-the-nation primary status. For Gramm, it was a one-two punch that knocked him out of the race. First, after boasting he’d win Louisiana and win it big, Gramm came in second to Patrick Buchanan. A week later, he finished fifth in the Iowa caucuses. Having peaked too soon, he quit the race two days later on Valentine’s Day.

Perhaps Texas breeds pols who are too big for their britches, since Gramm’s underwhelming, but well-financed, performance was matched by Democratic senator Lloyd Bentsen in 1976 (though Bentsen did serve credibly 12 years later as Michael Dukakis’s running mate) and by fellow party-switcher John Connally, the former governor and Nixon favorite who bombed in 1980.

There’s nobody quite like Mills or Gramm or Connally or Bentsen in the 2020 Democratic field, though you can argue the bumper crop of congressional candidates (six senators and four House members and counting) shows some Beltway self-regard in itself.

The Lifetime Non-Achiever

2. Rocky ’60, ’64, and ’68

Nelson Rockefeller had a distinguished early career in Latin American diplomacy and philanthropy and an impressive list of accomplishments as governor of New York over 13 consecutive years in that post. But his intense desire to become president was consistently frustrated. He briefly ran in 1960 before withdrawing in Richard Nixon’s favor, though not until he extorted platform concessions from the winner that permanently alienated outgoing president Dwight D. Eisenhower. Rocky was the front-runner for 1964 until his sudden divorce and remarriage damaged his personal standing significantly. He ran anyway, and after a crucial primary loss to Barry Goldwater in California (helped along by ill-timed news that his second wife had given birth), suffered an ignominious reception at that year’s Republican convention, when Goldwater delegates howled down his efforts to speak. In 1968, he decided not to challenge Nixon again but then changed his mind and jumped back into the race, with his sole message being his superior electability — which was ruined on the eve of the convention by a poll showing Nixon doing better against Democrat Hubert Humphrey.

Rocky was considering yet another presidential run in 1973 when he was appointed Gerald Ford’s vice-president. His political career ended when he was forced off the 1976 ticket by conservatives threatening to bolt to Ronald Reagan.

You have to go back to Robert Taft (’40, ’48, and ’52) to find Rockefeller’s equal as a three-time nomination-contest loser (not counting perennial candidates like Harold Stasson, or favorite sons). However, there have been many two-time losers who (unlike, say, Ronald Reagan) didn’t make up for it with a win or two along the way. There are Democrats Estes Kefauver (’52 and ’56), George Wallace (’64 and ’72), Gene McCarthy (’68 and ’72), Scoop Jackson (’72 and ’76), and John Edwards (’04 and ’08). Republicans include Lamar Alexander (’96 and ’00) and the aforementioned Rick Perry (’12 and ’16).

The only 2020 candidate in danger of becoming a three-time loser is Joe Biden (’88 and ’08). If he wins, he’d match Hubert Humphrey (’60, ’68, ’72) with a one-and-two record in nominating contests.

The Truly Spectacular Flop

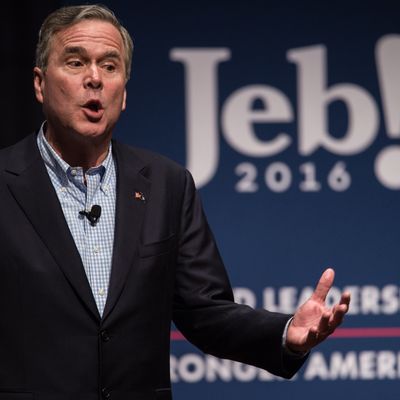

1. Jeb Bush ’16

Again, this is a subjective process, but it’s hard to think of a presidential candidate whose underachievement was so overwhelming and had such enormous consequences for his party and country. Jeb Bush entered the 2016 contest with the most valuable last name in politics, a massive fundraising machine, a boatload of elected official endorsements, strong positioning in the field ideologically, and a critical firewall state relatively early in the process (his home state of Florida). He was overwhelmingly the smart-money favorite, sure at least to survive until the late primaries.

Instead, he became a punching bag for Donald Trump in the debates and a steadily unpopular candidate in polls. And he wasted an enormous amount of his donors’ money as he stumbled toward defeat, as I noted at the time:

[Bush strategist Mike] Murphy described Donald Trump as a “zombie front-runner” doomed to fade into irrelevance when voters tuned in, got their signals from elites, and thrilled to the rich symphony of Jeb’s philosophy, record, biography, and electable message.

The irony, of course, is that by October of 2015 the term “zombie” best described the Bush campaign itself, pouring tens of millions of dollars a week into ads that did almost nothing.

Bush withdrew from the race before having to suffer the ultimate humiliation of being trounced by Donald Trump in Florida (that distinction was saved for fellow Floridian Marco Rubio). He ultimately earned a total of three delegates, which means he and his outside backers spent $53 million per delegate. The enduring epithet for Jeb’s candidacy was this incident in New Hampshire:

But there were so many such incidents that soon after he withdrew, Vox published an article titled “The 17 saddest moments of Jeb Bush’s very sad campaign.”

The main reason I listed Jeb! 2016 as the worst nomination-contest campaign is that I can’t imagine anyone matching this disaster in 2020 or in the foreseeable future. That it helped Donald Trump ascend to the presidency is the rancid cherry on top of the sundae.