Uber may be the company that is most emblematic of the most recent wave of Silicon Valley start-ups: amazing, industry-transforming convenience married to breathtaking rapacity, aggression, and general dickishness. Founder and ousted CEO Travis Kalanick’s combative strategy of expanding by entering new cities without permission, generally over the objections of regulators, has, despite some turbulence, paid off handsomely for the company, which is seeking a $100 billion valuation in its upcoming initial public offering. But the S-1 it filed yesterday in anticipation of the IPO reveals that a profitable future is far from a sure thing for Uber — and the cities over which it ran roughshod as it grew will have their opportunity for revenge, should they want it.

As much of the coverage of the S-1 has already noted, Uber does not, currently, make money. In fact, it loses money, and a great deal of it: $3 billion in 2018 alone. In fairness, it’s losing less money than it used to ($4.1 billion in 2017), but it’s also growing more slowly. The problem, as it stands, is that the math doesn’t quite add up: It’s difficult to provide an affordable rideshare service that is also an attractive proposition to the driver-contractors who make up Uber’s enormous — and increasingly angry — workforce.

One way of thinking about Uber is that it’s currently a kind of charity program in which wealthy investors — who are plowing money into a money-losing enterprise — and not-wealthy cab drivers — who, when all is said and done, earn something like minimum wage — subsidize low taxi rates for urban professionals. Obviously, it’s not actually a charity, but the idea is that Uber as it presently exists is not a particularly enticing business, and investors are willing to let it burn money for now not because they think that New Yorkers and Los Angelenos deserve cheap cab rides, but because they believe that Uber will eventually transform from a semi-charitable taxi app into a globally dominant transportation “platform,” encompassing all kinds of vehicles and all kinds of transported objects, and that at monopoly-scale, the economics of the business will fall into place.

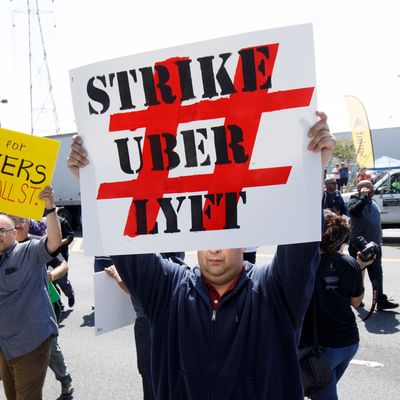

So what’s standing in Uber’s way? Those frustrated drivers, for starters. As drivers increasingly wake up to a structure and pay system that is much less lucrative than is often thought, and as Uber reduces its “driver incentives” (essentially, subsidies to encourage drivers to stay on the road), as the S-1 admits, “driver dissatisfaction will generally increase.” Worse still than generally dissatisfied drivers would be organized drivers, able to demand a change in their status from contractors to employees — meaning Uber would be obligated to provide benefits and a guaranteed minimum wage. Uber, according to its S-1, has 3.9 million drivers on its app, which, if they’re driving regularly, makes the company the largest employer on earth. As the S-1 puts it, “Any such reclassification would require us to fundamentally change our business model.”

It’s been clear for a while that angry and exploited drivers could, if organized, topple Uber as we know it. But as the S-1 shows, there’s another group that poses a potential existential threat to Uber: cities. “In 2018, we derived 24% of our Ridesharing Gross Bookings from five metropolitan areas — Los Angeles, New York City, and the San Francisco Bay Area in the United States; London in the United Kingdom; and São Paulo in Brazil,” Uber writes in the S-1. “An economic downturn, increased competition, or regulatory obstacles in any of these key metropolitan areas would adversely affect our business, financial condition, and operating results to a much greater degree than would the occurrence of such events in other areas.”

Uber will always have trouble in rural and suburban areas, where owning a car is cheap and common, and where rides take longer, come along less often, and are generally less likely to make drivers money in aggregate. Cities, which are dense enough to make driving an Uber a more lucrative undertaking, are always going to be Uber’s bread and butter — especially cities where car ownership is expensive, like New York, or where public transportation is lacking, like Los Angeles.

That makes for some pretty incredible leverage. The Kalanickian corporate premise that Uber can and should do what it wants in cities, regardless of regulators’ objections — and that it should pull out of markets, like Austin, that won’t bend to its will — all but collapses when you understand how much Uber depends on those cities as markets. In fact, cities hold a great deal of power over Uber. Put more bluntly, New York City might be able to destroy Uber, should it choose to. The S-1 notes New York’s recently implemented taxi regulations — which limit the number of new rideshare drivers, and implement minimum per-mile and per-minute rates — as examples of how new regulations in its major markets can adversely affect its business. San Francisco, for its part, may vote on a ridesharing surcharge this year. Why stop there? Transport for London recently came close to banning Uber entirely.

Okay, maybe cities don’t need to destroy Uber. The company takes rides away from public transportation, treats its drivers poorly, and has suffered in the past from an unbelievably toxic corporate culture — but the core technological innovation of its service is a genuine improvement. The point of leverage, anyway, is to use it, not to break it. If I were the mayor of Los Angeles or São Paulo, I might pay Uber a visit next week: It would be a real shame, I might say, nodding at the possibility of “accidentally” reclassifying its contract workers as employees, if something were to happen to your friendly regulatory environment …