The Trump administration is a government of Donald Trump and his cronies, for Donald Trump and his cronies, and by Donald Trump and his cronies.

The Democratic Party has put this allegation at the center of its case for evicting Trump from the Oval Office ASAP. It is the charge that unifies the myriad counts for his indictment: His tax cuts for the rich, attacks on health care for working people, machinations in Ukraine, and profiteering off the presidency all reflect the president’s commitment to putting himself first, his patrons second, and America … somewhere just below Saudi Arabia.

But while Democrats have done a decent job spotlighting Trump’s corruption and betrayals of the public interest, they haven’t always directed the electorate’s attention toward the president’s most (politically and literally) toxic acts of treachery. These days, when Democrats talk about Trump sacrificing the national interest to his own, they’re typically decrying his decision to withhold military aid from Ukraine. This is a natural consequence of the House’s worthwhile impeachment inquiry. And yet, it’s hard to believe there are many swing voters who’d put “countering Russian hegemony in the Donbass” on their list of top policy concerns. The idea that America has a vital national security interest in denying Russia the modest sphere of influence we’d once promised to allow it is tendentious on the merits. And few Americans have strong feelings about Ukrainian self-determination. By contrast, most U.S. voters do have deep-seated misgivings about corporations poisoning the air their kids breathe. And Donald Trump’s White House has made increasing the number of Americans who die prematurely from exposure to unhealthy air one of its top policy priorities.

On Monday, the New York Times revealed the administration’s latest effort on this front. Under federal law, the Environmental Protection Agency has broad discretion to enact rules safeguarding air and water quality, so long as it has strong scientific evidence demonstrating the harms of an existing industrial practice. By the same token, it is difficult for the agency to roll back existing environmental rules if the available science suggests that doing so would have profoundly adverse public-health consequences. But the Trump administration has devised a solution to both of these “problems”: Declare the bulk of the research demonstrating a link between air pollution and premature deaths unfit for consideration.

Specifically, Trump’s EPA has prepared a draft proposal that would bar it from considering the conclusions of any academic study that relies on confidential medical records. The official rationale for this policy is that such studies cannot be independently verified. Without access to the private medical records undergirding a given finding, EPA agents can’t double check the validity of the researchers’ raw data. But this is a standard that virtually no peer review committee or scientific journal insists upon, for the simple reason that private medical records are indispensable tools for documenting public-health outcomes — and assurances of confidentiality are often indispensable for securing private medical records.

Regardless, the administration’s true motivation has nothing to do with abstract questions of scientific ethics. The new rule’s most important component is that it can be applied retroactively. Which is to say, it can be invoked to block the renewal of existing environmental regulations that were enacted on the basis of studies involving private medical records. And that would encompass a lot of regulations. As the Times’ Lisa Friedman explains:

[A] groundbreaking 1993 Harvard University project that definitively linked polluted air to premature deaths, currently the foundation of the nation’s air-quality laws, could become inadmissible. When gathering data for their research, known as the Six Cities study, scientists signed confidentiality agreements to track the private medical and occupational histories of more than 22,000 people in six cities. They combined that personal data with home air-quality data to study the link between chronic exposure to air pollution and mortality … The Six Cities study and a 1995 American Cancer Society analysis of 1.2 million people that confirmed the Harvard findings appear to be the inspiration of the regulation.

“The original goal was to stop E.P.A. from relying on these two studies unless the data is made public,” said Steven J. Milloy, a member of Mr. Trump’s E.P.A. transition team who runs Junkscience.org, a website that questions established climate change science and contends particulate matter in smog does not harm human health.

The right’s assault on this line of public-health research is driven by an inconvenient truth: Air pollution turns out to be much worse for human health than just about anyone expected when the Clean Air Act was first established. The longer scientists have studied the issue, the more harms they’ve identified; human bodies simply did not evolve to process the kinds of particulate matter that coal and chemical companies spew. Earlier this year, a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences estimated that more than 100,000 Americans die from illnesses caused by exposure to air pollution each year. This reality has given evidence-based environmental policy a strong environmentalist bias. So the GOP’s corporate patrons are eager to destroy the evidence.

But this is one of the many instances in which the GOP donor class’s financial interests and the GOP’s political interests are in severe tension. There is a reason why President Trump has always claimed to care about clean air and water even as he ridicules climate change as a “Chinese hoax” — a large majority of American voters want the government to make sure they can breathe clean air and drink safe water.

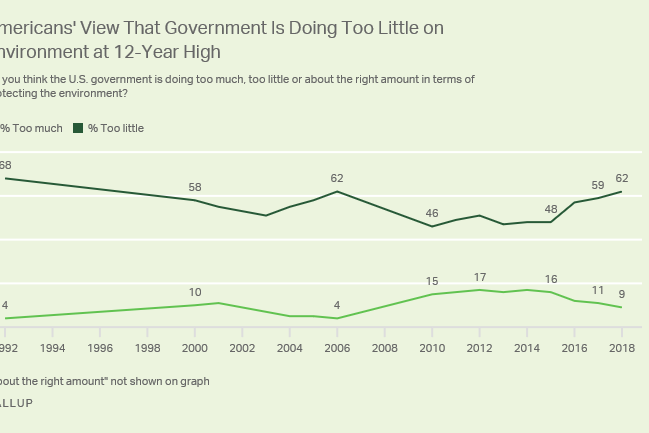

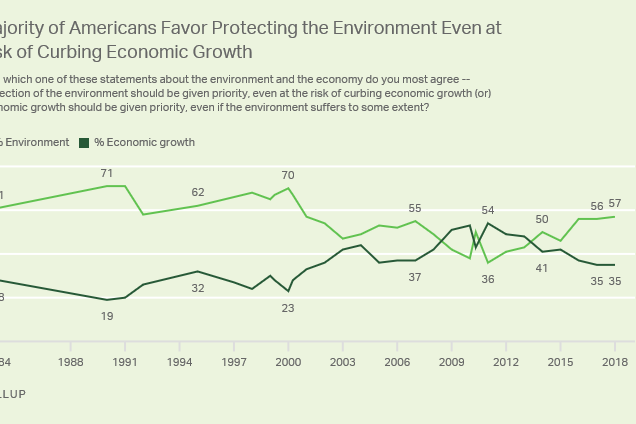

Last year, Gallup found 62 percent of Americans saying that the government was “doing too little” to protect the environment — the highest that figure has been in more than a decade. Meanwhile, some 57 percent of voters told the pollster that environmental protection should take priority over economic growth.

These preferences are reflected in the public’s evaluation of each party’s performance on environmental issues. In March, 59 percent of voters told Gallup that Trump was doing a “poor job of protecting the nation’s environment.” Around the same time, Morning Consult found voters saying that, on environmental issues, they trusted congressional Democrats more than Republicans by a margin of 50 to 27 percent. For context: On health care, which is widely seen as the Democrats’ best issue, their advantage over the GOP was merely 45 to 35 percent.

And Morning Consult’s survey was no outlier. In August 2018, an NBC News/Wall Street Journal survey found that Democrats had an 18-point advantage on health care and a 38-point one on the environment. In June 2017, Gallup showed voters preferring the Democrats on health care by a margin of 55 to 36 percent; on “the environment including global warming” that margin was 63 to 29.

In a loud, public fight over Trump’s EPA policies, Democrats wouldn’t just benefit from their superior credibility on the environment, but also that of their allied interest groups. The administration’s new draft proposal has already attracted praise from America’s premier lobby for chemical manufacturers, and criticism from the American Lung Association and the National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners. It seems unlikely that the median voter would trust Dow Chemical more than their child’s health-care providers in an argument over whether the president is exposing their children to dangerous chemicals.

Yet Democrats have failed to pick such a fight, or at least to do so in a manner that attracts sustained public attention. None of the party’s 2020 candidates has made the president’s assault on air quality a focal point of their advocacy on the debate stage or campaign trail. Much of the time, the issue gets subsumed under the broader one of climate change, which may be justifiable in substantive terms. But in political ones, there’s reason to think that voters find the prospect of toxic air more viscerally concerning, and eminently solvable, than that of climate change. To the extent that Democrats are looking to build up their support among affluent, Trump-averse suburbanites, that cohort does seem to have a penchant for freaking out about their offspring’s exposure to toxins (whether real or imagined).

It would be in the Democratic Party’s interest to increase the salience of environmental issues, even if Trump hadn’t spent the past two years running the EPA like the coal industry’s own private think tank. But the Trump administration has, in fact, done its best to write the Democrats’ attack ads for them. Since taking office, the president has (among other things) restored Dow Chemical’s freedom to sell an insecticide that scientists say causes neural damage in small children, defended the liberty of Texas coal plants to spew deadly amounts of sulfur dioxide into the skies above the Houston suburbs, and fought for the God-given right of coal plants to dump mining waste in streams.

It shouldn’t be that hard for a Democratic campaign, or associated PAC, to tell the stories of individuals who’ve been harmed by these policies in compelling 60-second spots. By doing so, the party could simultaneously increase the salience of its most favorable issue, reinforce the public’s preexisting suspicion that Republicans are too friendly with big business, and signal their solidarity with communities in rural America, where air and water pollution is often concentrated.

Trump’s quid pro quo with Ukraine was contemptible and worthy of impeachment. But his party’s noxious compromises with polluters may prove harder for swing voters to swallow.