I do not recommend reading the new books by Ezra Klein and Christopher Caldwell one after the other. Klein’s Why We’re Polarized and Caldwell’s The Age of Entitlement come from very different perspectives, but convey a near-paralyzing and plausible pessimism. Klein’s is a political-science explanation of our intensifying cultural and political tribalism, and its incompatibility with functional liberal democracy (a theme I explored here). Caldwell’s is a deeper, wider cultural and constitutional narrative of the last half-century. If Klein is trying to explain why polarization fucks everything up, Caldwell is intent on telling us how this state of affairs came to be. Both are well worth reading (though Caldwell’s vibrant, mordant prose makes his a more unusual and enjoyable ride).

Some might say that the two are among the best and the brightest of left and right, respectively. On the left, Klein is a near-archetypal member of the new elite class: progressive but still struggling to be fair-minded, a liberal who has tactically deferred to wokeness. On the right, Caldwell swaggers around as the cranky-cool professor articulating the frustrations of the less articulate, throwing barbs here and there, gleefully challenging and scorning the elite orthodoxies that culminated in the election of Barack Obama. (Klein is the founder of Vox.com, which is also owned by New York magazine’s parent company, Vox Media. )

But both books agree on one central thing: Our fate was almost certainly cast as long ago as 1964 and 1965. Those years, in the wake of the Kennedy assassination, saw the Civil Rights Act upend the Constitution of a uniquely liberal country in order to tackle the legacy of slavery and racism, and the Immigration and Nationality Act set in motion the creation of a far more racially and ethnically diverse and integrated society than anyone in human history had previously thought possible. Still, at the time, few believed that either shift would have huge, deep consequences in the long term. They were merely a modernization of American ideals: inclusivity, expansiveness, hope.

As someone who was born just before these two changes were instigated, I regarded those tectonic shifts as simply part of the landscape — something that seemed always to have been here. And what could be questioned about either? One was reversing a profound moral evil; the other was banishing racism from the immigration laws. No-brainers. The strongest resistance to civil rights came from former segregationists or obvious racists, and there was little resistance to the Immigration Act, because most in the congressional debate seemed to think it wouldn’t change anything much at all. (The House sponsor of the Immigration Act, as Caldwell notes, promised that “quota immigration under the bill is likely to be more than 80 percent European,” while Ted Kennedy insisted: “The ethnic mix of this country will not be upset.”) There were a few dissenters to the 1964 Act, such as Robert Bork, who identified a significant erosion in the freedom of association. And there were southern senators who worried about immigrants from the developing world. But the resisters were easily dismissed on both counts, in the wake of LBJ’s 1964 landslide.

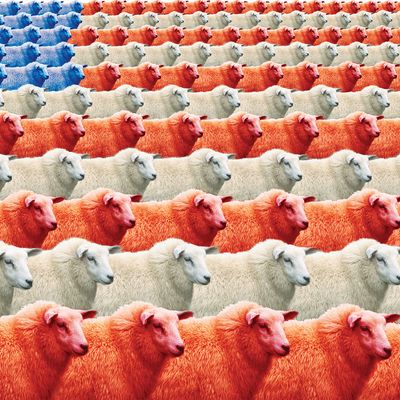

In fact, as Klein shows, a pivotal moment had arrived. The civil-rights movement quickly broke apart the old Democratic party, which had for decades combined the interests of blacks and southern whites into a single multiracial coalition. The result was a sorting of the two political parties into much purer vessels for their diverging ideologies, and into groupings that were also increasingly racially distinct. The GOP became whiter and whiter; the Democrats more and more became the party of the marginalized nonwhites as the years rolled by. Blacks and southern whites ceased to communicate directly within a single party, where compromises could be hammered out through internal wrangling. In the aggregate this was, as Klein emphasizes, a good thing — because blacks kept coming out the losers in those intraparty conversations, and with civil rights, they had a chance of winning in a clearer, less rigged, debate.

But it was also problematic because human beings are tribal, psychologically primed to recognize in-group and out-group before the frontal cortex gets a look-in. And so the whiter the GOP became, the whiter it got, and the more diverse the Democrats got. Simultaneously, the economy took a brutal toll on the very whites who were alienated by the culture’s shift toward racial equality, and then racial equity. Klein recognizes that this racial polarization, is, objectively, a problem for liberal democracy: “Our brains reflect deep evolutionary time, while our lives, for better and worse, are lived right now, in this moment.” So he can see the depth of the problem of tribalism — and its merging with partisanship, which goes on to create a megatribalism.

If humans simply cannot help their tribal instincts, then a truly multicultural democracy has a big challenge ahead of it. The emotions triggered are so primal, that conflict, rather than any form of common ground, can spiral into a grinding cold civil war. And you can’t legislate or educate this away. One fascinating study Klein quotes found that “priming white college students to think about the concept of white privilege led them to express more racial resentment in subsequent surveys.” Anti-racist indoctrination actually feeds racism. So tribalism deepens.

Klein sees this spiral more clearly than most on the left. He acknowledges the truth that in a period of extraordinary demographic and racial change — the U.S. is the first majority-white nation that will become majority nonwhite in human history — every group begins to feel like an oppressed minority. Including whites: “To the extent that it’s true that a loss of privilege feels like oppression, that feeling needs to be taken seriously, both because it’s real, and because, left to fester, it can be weaponized by demagogues and reactionaries.” And the truth is: It was left to fester. Whenever whites resisted ever-expanding concepts of civil rights or mass illegal and legal immigration, they were cast outside the arena of permissible disagreement, deemed racists, and stigmatized. Even the GOP scorned them. Eventually, Hillary Clinton named them: the deplorables. By 2016, plenty of Americans decided to embrace the label, and voted for Trump.

Caldwell’s account is indispensable — especially for liberals — in understanding how those resentments grew until they finally exploded under Barack Obama. The Tea Party was the first real movement of this sort; the collapse of immigration reform proposals under George W. Bush and then under Obama revealed how powerful these feelings were; Trump managed to wrap them all up into a populist fervor that was distributed geographically enough to give him a win in the Electoral College. Liberals, increasingly ensconced in their own economic and social bubble, were shocked.

Caldwell’s book is far too nuanced and expansive to cover here. But he identifies key moments and key changes. The 1965 Immigration Act was the beginning of a huge experiment in human history. It was complemented by open bipartisan-elite toleration of mass undocumented immigration across the southern border. And civil rights became something other than ending racial discrimination by the state: It became a regime of ending discrimination by individuals in economic and social life; then it begot affirmative action, in which race played an explicit part in an individual’s chance of getting into college; and it culminated in the social-justice agenda, which would meaningfully do away with the American concept of individual rights and see it replaced by a concept of racial group rights. Caldwell sees the last 50 years as a battle between two rival constitutions: one dedicated to freedom, the other to equality of outcomes, or “equity.” And I think he is right to see the former as worth fighting for.

But how do we get out of this trap? That’s where the depression sinks in. Neither Caldwell nor Klein see a way back to a common weal and a common good. Ezra offers some technical corrections — ending the Electoral College, the filibuster, and winner-takes-all voting. And they might help, although their potential unintended consequences should be carefully considered. Then he recommends meditation to control our own primal instincts — a role that Christianity traditionally held. (I don’t disagree with Ezra on the benefits of meditation, but it’s hardly a game-changer in America in 2020.) Caldwell proposes something far more drastic: a repeal of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Yes, you read that right. The proposal’s perversity matches its impossibility — and it’s buried in one sentence on the penultimate page of the book.

So much of Caldwell’s polemical history is fresh air; but the bleakness of its reactionary mood reveals how tribal Caldwell has become. He can barely eke out a few sentences reluctantly acknowledging some of the good things that the last 50 years have brought — in the lives of many women, in the prospects for African-Americans, in the dignity of homosexuals. He never acknowledges that Obama actually stood a chance of healing racial divides, if the GOP hadn’t demonized him from the start. And as an old friend of Chris’s, I know him to be a more gracious and humane person than this polemic might, at times, suggest. But that such a good man has gotten caught up in polarization and tribalism and such a brilliant man sees no hope for a peaceful resolution merely reveals how deep our problem is.

I have a smidgen more optimism. I see in the long-delayed backlash to the social-justice movement an inkling of a new respect for individual and creative freedom and for the old idea of toleration rather than conformity. I see in the economic and educational success of women since the 1970s a possible cease-fire in the culture wars over sex. I see most homosexuals content to live out our lives without engaging in an eternal Kulturkampf against the cis and the straight. Race? Alas, I see no way forward but a revival of Christianity, of its view of human beings as “neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.” This means such a transcendent view of human equality that it does not require equality of outcomes to see equal dignity and worth.

Yes, I’m hoping for a miracle. But at this point, what else have we got?

The Dangers of Quoting Shakespeare

Alastair Stewart is arguably one of the most neutral, professional, and well-loved of British newsreaders. (And I love that the English still use that term newsreader, rather than “reporter” or “anchor” for the nightly news.) He’s been doing his thing for over 40 years (I have memories of his dulcet tones in the 1980s) and is near-universally loved. But he made the mistake of engaging on Twitter. He did so impeccably, as far as I can see. And one of his responses to angry trolls (he has used it once before) has been simply to provide a quote from Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure. Here it is, in all its brilliance:

But man, proud man,

Dress’d in a little brief authority,

Most ignorant of what he’s most assur’d—

His glassy essence—like an angry ape

Plays such fantastic tricks before high heaven

As makes the angels weep; who, with our spleens,

Would all themselves laugh mortal.

As a description of Twitter users, it’s hard to beat “dress’d in a little brief authority / Most ignorant of what he’s most assur’d.” But of course, someone regarded this use of Shakespeare as racist. One Martin Shapland saw Stewart’s use of the quote and accused him of referring to him as an ape. They were having a Twitter spat over the monarchy, of all things. A series of tweets between the two that have been recovered are completely anodyne. In that exchange, Shapland leapt at the chance to accuse someone he was disagreeing with as a racist. “Just an ITV newsreader referring to me as an ape with cover of Shakespeare. Measure for Measure, Stewart is a disgrace,” he tweeted. Stewart replied with an emoji of a saint smiling. Shapland made the usual activist move: “Could I ask what @ITV, and @ITVNews … think of this?”

The suits at ITV then strong-armed Stewart into an abrupt retirement under a cloud of innuendo. Shapland has claimed without evidence that there were other tweets in a thread that cast Stewart in a bad light, but he has since deleted them, and Stewart’s account has also disappeared, so we can’t see for sure. ITV, Stewart’s boss, has cited his “multiple errors” on social media, again without providing details. Stewart acknowledged a “mistake” which he regrets. But the smear of racism hangs over him, as it was designed to.

In the aftermath of the fuss, Stewart has been widely hailed by all his colleagues as a model figure, an adored gentleman-mentor to many nonwhite journalists. News anchors broke into tears announcing his sudden banishment from the TV. And Shapland? His Twitter feed gives you a sense of where he’s coming from. See if you can spot a theme here: “Fucking white privilege.” “Typical white guy”; “Very white. Very male. Very pale. Very rich?” “Is this contributor white?” “The White People are at it again.” And what’s interesting to me is that Shapland feels utterly secure that, as a black man, he is entitled to use broad, generalizing insults of another race, and indeed should be celebrated for doing so. (The other time Stewart quoted this Shakespeare passage was with a tweeter who was white.)

The great truth about today’s version of anti-racism is that it’s racist. Marinate people in race consciousness; teach them to see racism everywhere; reward them for calling out, Stasi-like, their fellow citizens for thought-crimes; punish the “racist” pour decourager les autres; and repeat the ideological cleansing process. (The same is true of left feminism: tweets announcing hatred of all men are actually celebrated, or dismissed as irony.) Set up a system which rewards this kind of group hatred, and human nature will do the rest.

I’m not sure what the upshot of this is, but there’s a huge outcry from viewers in Britain, countless broadcasting colleagues, and a petition to get Stewart reinstated. (Sign here.) This follows another explosive accusation of racism against a “white privileged man,” the actor Laurence Fox, by a woman of color on BBC’s Question Time panel show. Fox turned the conflict around by calling the woman a racist by reducing him to his immutable characteristics, to audience applause. As the public gets to know and understand more about the left racism now coursing through the entire Anglo-American media, they like it less and less.

And maybe it’s a good moment to see where we are. A man quotes Shakespeare comparing “man, proud man” with “an angry ape.” Any literate person can see that Shakespeare is not talking about race at all; he’s talking (rather presciently) about human beings’ deeper, more primal natures that can obscure our rational thought. But Shapland instantly thought he was being attacked for being black. The distortion and poisoning of the mind here is quite something to behold. And mourn.

Weren’t They That ’80s Band?

Now that I’m on my third antibiotic regimen to get rid of a post-op sinus infection, I needed cheering up. Right on cue, the Pet Shop Boys have just released their 14th album, Hotspot — just as good as their first. I know, I know. You’re thinking: Weren’t they that ’80s band? And there’s a reason you do. There is no place on American radio any more for the kind of elegiac synth-pop Neil Tennant and Chris Lowe have regularly created the past three decades. They disappeared from American TV screens as well after the homoerotic video for their single “Domino Dancing,” which unnerved the suits at MTV. They’re still hugely popular worldwide, filling stadiums in Brazil and Japan and Germany, and this new album now looks likely to be the best-selling album in the U.K. this week — something they also achieved 26 years ago. That’s quite some staying power.

I love them for many reasons. Their lyrical sophistication is rare: Through disco beats, you get references to Rebecca West, Gerhard Richter, and Tony Blair. Their love of high-energy pop is hard to equal. On their last album, they had a song “Burn,” which is almost the apotheosis of every disco song you ever loved — remade. They’re a pop group that wrote an entire symphony to go along with Sergei Eisenstein’s legendary silent film, Battleship Potemkin, and then played it live with an orchestra in front of a massive screen in Trafalgar Square. They have had residencies with the Royal Opera House. In each song, they somehow manage to create an atmosphere, a sense of place, and a sound that transports you. And as a gay man, they have particular resonance. They channeled the energy and liberation of the 1980s and then the despair and grief of the 1990s. Most will not have noticed that the songs they put out were about AIDS, which is another reason I like them. Their lyrics are subtle — and have recently been published in book form as poetry. But listen to “It Couldn’t Happen Here,” “Your Funny Uncle,” “Dreaming of the Queen,” or “The Survivors.” As a creative voice during the worst of the plague and after, they are absurdly underrecognized.

As their career continued, they switched from giving almost no live performances — or totally deadpan ones — to putting on extraordinary concoctions of light and sound and choreography. They did this even with Chris still sitting there glum or expressionless on keyboards, and Neil not exactly trying to dance. I went to one of their first U.S. concerts, held in a college arena, and it was somewhat crude. And I went to their tour for Super, which came to D.C. the weekend after Trump’s election, and was dazzled by the imagery and choreography. At that moment of despair, it was as if an angel had sent them. And this album is as solid as their previous ones, part of a trilogy produced by the extraordinary Stuart Price.

What is the secret to their longevity? I know it sounds an odd thing to say of a pop group, but I think it’s their integrity. They’ve made some huge hits, but they never pander. They have kept their private lives private in ways every celebrity should but doesn’t. They constantly experiment, but classic songwriting remains at their core. I find that over the decades their music has been a soundtrack for my own life — including, now, the onset of aging, after thinking once I would never survive this long. And they have grown older in a way that so many pop and rock stars haven’t. They have kept their dignity and their energy. They have never lost their souls.

See you next Friday.