More than usual, and perhaps more than any other individual factor, fear has dictated the mood and direction of the 2020 Democratic presidential primary. In its least frantic iteration, it has manifested as an outsize focus on candidates’ electability — not an unheard of preoccupation for a political race, to be sure, but one whose salience this time around has Democratic voters more willing to forego their ideological preferences in favor of what they see as a sure bet. But fear remains the driving force. The prospect of another four years of President Trump has these voters in a state of stratospheric anxiety, driving many into the camp of the most familiar candidate in the race: Joe Biden. That the former-vice president spent several decades in the U.S. Senate and eight years in the White House as second-in-command to the still-beloved President Obama has many convinced that his abundant liabilities — his age and its attendant mental decline, his electability pitch heavy on nostalgia but light on reformist approaches to health care, housing, and wealth inequality that would more decisively quell the nation’s economic woes and psychic unease — are of ancillary concern.

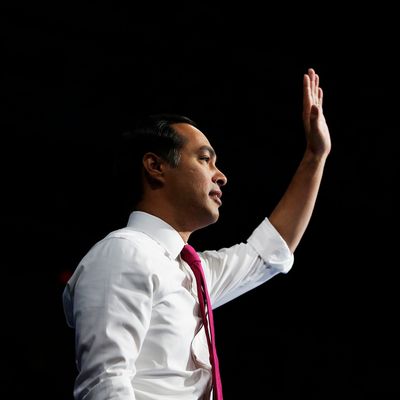

It has not been an election amenable to the candidacy of Julián Castro, who announced on Monday that he was dropping out of the race after months of low polling, fundraising difficulties, and failure to qualify for two consecutive debates. “I’m so proud of everything we’ve accomplished together,” he wrote in a tweet announcing his decision. “I’m going to keep fighting for an America where everyone counts — I hope you’ll join me in that fight.” Castro built his campaign on promises to advocate for America’s most vulnerable, namely black and brown people caught up in the criminal-legal system, undocumented immigrants, people with disabilities, and the poor. This was a gamble by any measure in a race where moderate white suburbanites and Rust Belters have become its most coveted voting blocs, but even more so for a young Mexican-American with limited political experience facing a general electorate that had recently sent the most virulently anti-Latino president in memory to the White House.

Castro boasted the field’s most radical plans to address police violence and decriminalize undocumented immigration, and conveyed an otherwise scarcely considered understanding of how seemingly colorblind policies — like gun buybacks — could imperil communities already targeted for aggressive law enforcement. He stayed on message even as his campaign’s prospects looked increasingly dire in its final weeks and became overshadowed by his insistence that the rules for debate qualification be changed to give him and other flailing campaigns, like that of Senator Cory Booker, a better chance. While some of his gripes were understandable — the disproportionate influence of Iowa and New Hampshire in deciding the nominee does, in many ways, disserve the Democratic electorate’s diversity — his failure is more likely attributable to the simple fact that most voters polled, including the nonwhite ones presumed to be his natural constituencies, weren’t sold on him.

But even as he failed to convince them of his electability, his ideas were praised widely for their nuance and attention to subjects and populations usually considered too niche — and by some measures, too divisive — to form the basis of a successful presidential campaign. Castro’s failure this election will do little to silence critics of such an approach. In the wake of Hillary Clinton’s defeat in 2016, backlash consumed much of the liberal-left punditocracy against what it dubbed “identity politics,” the practice of segmenting voters into subgroups on the basis of race or gender and appealing to the specificity of those experiences. It seemed at the time to stem from a straightforward impulse to recenter the desires of white heterosexuals, many of whom felt their status as the focal point of American cultural and political life was under threat. But it was also a thinly veiled rebuke to the politics and approach of the Black Lives Matter movement, which for more than two years by that point had been unwavering in its insistence — apparently controversial for many — that black people experienced a unique kind of maltreatment within the criminal-legal system specifically, and society more broadly.

Its demands that these disparities be taken seriously and addressed through policy as well as new social norms provoked backlash. Much of Trump’s Republican National Convention that year was devised in tacit opposition, with guest speakers like Rudy Giuliani and then-Milwaukee County Sheriff David Clarke railing against protesters and the eventual president painting a picture of an America besieged by street-level lawlessness and vowing a return to “law and order.” It would’ve taken a profound bravery and defiance of status quo thinking around racial justice to reject their appeals then. Nearly four years later, with rates of police violence largely unchanged and undocumented children being locked in cages as a matter of policy, it will take a similar level of moral courage to back a campaign that takes confronting these issues as its top priority, as Castro’s did.

Even so, there remain abundant opportunities for bravery this cycle. Bernie Sanders is yet again testing American voters’ appetite for socialism, and by extension insisting on a more humane approach to health care, social services, debt, and foreign policy than many of us have seen in our lifetime. A successful Sanders presidency, and even an Elizabeth Warren one, would usher an investment in social welfare not experienced since the Great Society and possibly the New Deal era — albeit with a more robust skepticism towards capitalism, in Sanders’s case, and less reliance on capitulating to virulent bigots when determining who gets to benefit from them. But the lack of support for Castro’s dogged focus on the undocumented and the criminalized betrays, in part, a reticence among voters to prioritize these issues foremost, and in some cases an assumption that a more humane economic policy will have a trickle-down effect on them anyway. Paired with the questionable prospects of a candidate of color not named Barack Obama in a Trump-friendly electorate, and the level of nerve required to submit Castro to the general election falls out of reach for many. These are defensibly reasoned and generally pragmatic rationales for his failure to gain traction. But they also illustrate the dire prospects facing any dedicated racial justice candidacy moving forward. Only on rare occasions have significant shares of Americans, if not majorities, united in agreement that human rights for black and brown people should be a major national priority. It would’ve taken a degree of courage to invest in Castro even to the extent that primary voters have invested in other middle- to top-tier candidates — like Pete Buttigieg and the recently dropped-out Kamala Harris — that the anxieties of the Trump era have left too many Democrats ill-equipped to show.