Five years ago, Benjamin Netanyahu informed the U.S. Congress that the Iranian government, and the terrorist group ISIS, were two different flavors of the same poison.

“Iran and ISIS are competing for the crown of militant Islam,” the Israeli prime minister told the House of Representatives, in an address aimed at blocking the Obama administration’s pending nuclear agreement. “One calls itself the Islamic Republic. The other calls itself the Islamic State. Both want to impose a militant Islamic empire first on the region and then on the entire world. They just disagree among themselves who will be the ruler of that empire.”

The upshot of this analogy was simple: If you wouldn’t trust ISIS to engage in good-faith diplomacy, you shouldn’t trust the terrorist regime in Tehran to do so either.

American hawks beat the same drum. The Islamic Republic’s terroristic irrationality was the keystone of their argument. After all, if Iran were a normal nation-state — endowed with an instinct for self-preservation, and an accurate understanding of its own limited power — then it would pose no dire threat to the U.S. or its allies. Objectively, Iran is a minor, regional power that has no rational use for a nuclear weapon except as a deterrent against foreign aggression. If Iran possesses reason, then its possession of an atom bomb would not risk genocide, but merely shift the balance of power in the Middle East. In which case, there would be every reason to give diplomacy a chance — and little excuse for the saber-rattling Netanyahu’s American admirers so keenly desired.

Five years later, it is now indisputable that this was, in fact, the case. The nuclear deal did not collapse beneath the weight of Iran’s bad faith, but beneath that of our own. And if Iran’s attempts to uphold that agreement did not put its rationality beyond dispute, its response to the killing of Qasem Soleimani surely must.

The Quds Force commander may have been a war criminal in the eyes of many Iraqis and Syrians. But within the Islamic Republic, Soleimani was a celebrated war hero. An estimated 1 million Iranians turned out for his funeral; at least 56 of whom lost their lives to the perilous scale of their nation’s grief, their bodies crushed beneath a stampede.

In the face of national mourning and humiliation this profound, even the most rational of nation-states would be liable to overreact. After violating its diplomatic promises, and imposing draconian sanctions on the Iranian economy, the United States had just assassinated a high-ranking Iranian official in brazen defiance of international law. How would an ISIS-like entity, whose thirst for the blood of infidels outstripped its concern for its own survival, respond to such an attack?

Would it wait a couple of days for the United States to increase security at its bases in Iraq, fire 22 missiles at two of the hardest targets it could find, and then — having killed zero Americans — declare that its national hero’s death had been avenged, and seek a truce with his killer? If this hypothetical sounds ludicrous to you, then Donald Trump’s characterization of the Iranian regime should too.

In remarks to the nation Wednesday morning, the president wisely shrugged off Iran’s tepid retaliation. But even as he implicitly acknowledged Tehran’s restraint, Trump reaffirmed the right’s conception of Iran as a “terrorist” state. He did not deride Soleimani as a war criminal, but as “the world’s top terrorist,” described Iran as the world’s “top sponsor of terrorism,” and claimed that its “pursuit of nuclear weapons threatens the civilized world.”

For the moment, Iran’s prudence, and Trump’s willingness to take the “win” Tehran tacitly offered him (lightly damaged bases being a small price to pay for Soleimani’s life), has brought us back from the precipice of war. But if Americans wish to maintain our distance from that ledge, we will need to recognize that our government brought us to this point by stoking fears of a phantom threat.

The Iranian “threat” is an American fever dream.

Iran does pose a serious threat to American influence in Iraq, and Saudi hegemony in the Middle East. Its Islamist regime also represents a modest (though not “existential”) threat to Israeli security and regional influence, as well as a fundamental obstacle to the personal freedom of Iranians in general, and Iranian women and LGBTQ individuals in particular.

But Iran poses no serious threat to American national security.

That last fact is inconvenient for U.S. foreign-policy elites who would like to sacrifice American lives and wealth to the causes of maximizing Washington’s influence in Iraq, Riyadh’s hegemony in the Persian Gulf, Israeli security, or regime change in Tehran (most of the Trump administration’s foreign-policy hands fall into at least one of those buckets). Persuading America’s infamously provincial public to embrace an expansive conception of their nation’s “core interests” — let alone the specific conception favored by America’s anti-Iran hawks — is hard. Persuading Americans that they have an interest in not dying in a terrorist attack is, by contrast, fairly easy. For this reason, a defining feature of American foreign-policy discourse is its willful elision of the distinction between threats to U.S. interests (as tendentiously defined by elite policy-makers) and threats to the physical security of the American people.

Anti-Iran hawks aren’t the only ones who engage in this rhetorical sleight of hand. It is endemic to Washington’s foreign-policy community. House Democrats, and the State Department officials who testified at their impeachment hearings, routinely described Russia’s incursions into the Donbass as a threat to America’s “national security” — as though the only thing standing between Vladimir Putin’s declining petro-state and geopolitical parity with the world’s preeminent economic and military power was control of an impoverished, environmentally degraded slice of Eastern Ukraine. More broadly, the equation of challenges to American “regional interests” with threats to the nation’s domestic security is baked into our government’s basic vocabulary: The White House’s principal foreign-policy planning body is not called “The Geopolitical Strategy Council” but rather, the National Security Council, even though the bulk of its activities have little to do with securing the American nation-state.

But the Trump administration, and its allied anti-Iran hawks, conjure phantom threats to American security with exceptional fervor and mendacity. And not without reason: If Americans had a clearer understanding of the nature of “the Iranian threat,” they would likely have less tolerance for Donald Trump’s belligerent posture toward Tehran.

When the president designates Iranian state institutions as“terrorist” organizations, he is inviting the public to associate the Islamic Republic with the kind of violence their nation experienced on September 11; which is to say, mass casualty attacks on the American homeland. In recent days, Vice President Mike Pence made this subtext explicit by ludicrously accusing Soleimani of involvement in 9/11. And yet, Iran has never perpetrated mass violence on U.S. soil. Further, as Jefferson Morley noted last year in The New Republic, the last fatal terrorist attack on Americans abroad that could plausibly be attributed to Iranian proxies was the Khobar Towers bombing in 1996. Soleimani and his government are doubtlessly complicit in reprehensible violence against civilians across the Middle East, and for the deaths of U.S. soldiers in Iraq. But targeting the uniformed military officers of an army that invaded and occupied a country on false pretenses, and in defiance of international law, is not terrorism by any reasonable definition (no matter how pointlessly destructive and morally odious such attacks may be). The significance of this point isn’t merely semantic. The Trump administration would like us to see Iran’s willingness to target American troops in Iraq as indicative of the regime’s interest in threatening the security of American civilians in the U.S. And there is little basis for that deduction.

Unfortunately, equating the threat that Iran poses to America’s arguable interests abroad with a threat to Americans’ security at home is a bipartisan enterprise. Which is likely one reason that a new HuffPost–YouGov poll finds that 71 percent of American voters consider Iran “a serious threat to the United States.”

The road to war with Iran was paved (primarily) by U.S. policymakers.

Iran’s theocratic regime is loathsome in many respects. But it is not an implacable foe of the United States, or an irrational terrorist state, and its current hostility toward the U.S. is largely the product of American policy choices.

To appreciate this point, consider some pieces of context for the U.S.-Iran conflict that are routinely elided in the American press.

• When Donald Trump was 7 years old, the United States orchestrated a coup against Iran’s democratically elected government, leaving its people subject to the rule of an authoritarian, pro-American regime for decades afterward.

• Shortly after Iran’s Islamic Revolution overthrew that regime, the U.S. aided Saddam Hussein’s Iraq in its invasion of Iran, a war of aggression that claimed hundreds of thousands of Iranian lives. In addition to more conventional forms of assistance, our government knowingly abetted Saddam’s illegal chemical-weapons attacks, even as the Iraqi dictator was deploying sarin gas against his own people. Thousands of former Iranian soldiers still suffer from health problems caused by such attacks.

• In 1988, the U.S. military fired a surface-to-air missile at a passenger plane flying in Iranian airspace and incinerated 290 innocent people. Iran did not retaliate militarily.

• Despite these historical grievances, in the wake of the 9/11 attacks, Iran rounded up suspected Al Qaeda members who had crossed its border with Afghanistan, made copies of their passports, passed their information along to the U.S. government, and allowed American officials to interrogate many of the detainees. James F. Dobbins, the Bush administration’s top negotiator on Afghanistan during the period, later said that Iran had been “comprehensively helpful” in “working to overthrow the Taliban militias’ rule and collaborating with the United States to install the Karzai government in Kabul.” Amid this collaboration, the Iranian government made diplomatic overtures to the George W. Bush administration, seeking comprehensive negotiations over the various areas of conflict between the two countries. Its offer was rebuffed. The U.S. president cast Iran as a member of an “axis of evil” along with Iraq and North Korea, and his administration proceeded to openly advocate for the overthrow of the Iranian regime.

• The United States then invaded and toppled the government of Saddam Hussein, which did not have nuclear weapons, while declining to militarily confront North Korea, which, by the end of Bush’s tenure, did.

• In 2015, the United States reached an agreement with Iran, Britain, France, and Germany that it would suspend sanctions on companies and countries that did business with Iran, so long as Tehran suspended its nuclear weapons program. The Iranian regime proceeded to do just that, ditching its highly enriched uranium and tolerating an invasive inspection program.

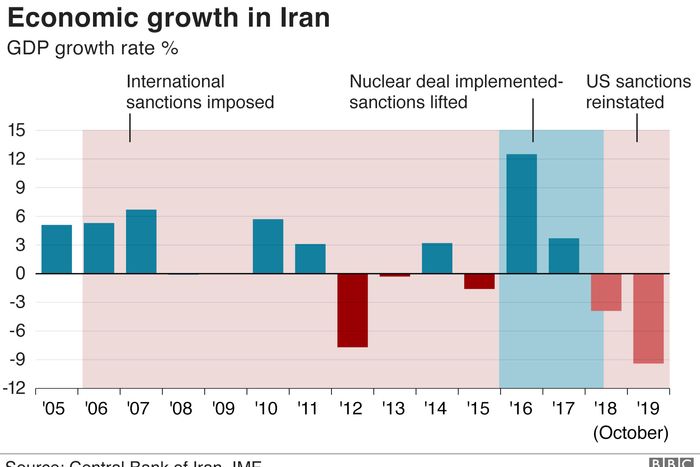

• Three years later, the U.S. violated that agreement. Despite Tehran’s undisputed compliance with the deal — and over the objections of its core allies — the U.S. imposed draconian new sanctions on Iran, along with any European companies that dared to invest in it. Those sanctions have plunged the Iranian economy into a devastating recession. Its currency has halved in value. For ordinary Iranians, the cost of living has skyrocketed. For many seriously ill Iranians, the cost of staying alive has proved prohibitive.

This list obviously represents a potted history of the U.S.-Iran conflict, one that highlights the latter nation’s grievances to the exclusion of the former’s. My aim here is not to provide a comprehensive account of relations between the two countries, but merely to offer a corrective to U.S.-centric coverage of the conflict, so as to help Americans better understand the nature of the Iranian “threat” they supposedly face.

The Trump administration portrays Iran as an irrational, revolutionary regime that has intervened in Iraq and Syria for purely offensive purposes, and seeks a nuclear weapon for potentially genocidal ones. But that narrative has much less credibility when Iran’s actions are viewed in historical context.

Take Iran’s actions in Iraq. Is Tehran’s interest in securing hegemony in a border state that once launched a devastating eight-year war against it difficult to understand? Is the regime’s desire to minimize the influence of the United States in Iraq irrational, given America’s past support for Saddam’s invasion, and perennial calls for the overthrow of the Iranian regime? Imagine that Iran had spent the 1980s aiding a Mexican invasion of the United States that had resulted in hundreds of thousands of American deaths. If Iran then invaded Mexico decades later and toppled its government — while loudly declaring its desire to affect regime change in the U.S. next — might the U.S. government rationally conclude that countering Iranian influence in Mexico was among its vital national-security interests?

Or take Iran’s alleged pursuit of a nuclear weapon. Would it be irrational for Iran to observe what happened to Iraq and Libya — and what didn’t happen to North Korea — and conclude that a nuclear weapon would constitute a vital deterrent against foreign aggression?

Finally, consider Iran’s most recent provocations. If a foreign power imposed sanctions on any entity that invested in the United States — in direct violation of an agreement that that foreign power had signed with the U.S. — and our country proceeded to suffer a devastating recession, might our government feel a need to impose costs on the foreign power in question for its diplomatic treachery?

The point of these thought experiments is not to justify the Iranian regime’s behavior, but merely to try to understand it. Just because Tehran has intelligible reasons for seeking dominance in Iraq does not mean that it has morally legitimate ones. What it does suggest, however, is that the Iranian regime’s restraint Tuesday night was characteristic, not aberrational: The Iranian regime is not an irrational, inscrutable aggressor that cannot be dealt with like any other state. This point should never have been controversial; even Iran’s bitterest adversaries in the American and Israeli security Establishments have long described the regime as “very rational.” And history supports their assessment. Iran did not shrug off America’s accidental incineration of an Iranian passenger plane, or provide aid to the U.S. after 9/11, out of its exceptional benevolence. Rather, it did so in deference to the same rational assessment of the limits of its own power that tempered its retaliation Tuesday night.

The Iranian regime is interested in making peace with the U.S. — even on starkly inequitable terms — because it is aware of its own relative weakness. America’s current regime, on the other hand, is only interested in making peace on entirely one-sided terms because it is aware of the very same thing. Put differently, the Trump administration’s hardline stance toward Tehran is predicated on the very truth that its propaganda is designed to obscure: It is precisely because Iran does not pose a serious threat to the United States that we can afford to blithely violate our agreements with its government, or assassinate its generals, and receive only “a little noise” in return.

Exactly why this White House decided to press America’s advantage over Iran to the point of risking another Middle Eastern war is unclear. What is clear, however, is that the administration does not trust the American people to endorse its true reasoning, and is therefore trying to make us fear an illusory threat.