On Sunday afternoon, nearly two weeks into his self-imposed isolation at home in Delaware, Joe Biden joined a private conference call for 72 donors from the Atlanta area. Biden, now the all-but-presumptive Democratic presidential nominee in a race frozen by the coronavirus, had recently been taking heat for his relative absence in the national conversation while Donald Trump’s inept response to the crisis flooded cable TV and headlines. (“Where is Joe Biden?,” went the refrain from frustrated Bernie Sanders supporters, some jittery Biden fans, and plenty of Trumpy trolls.) On the phone — a substitute for the in-person address he’d been scheduled to give donors gathered by former Coca-Cola CEO and chairman Muhtar Kent — he criticized the president and congressional Republicans, insisted that true leadership required truth-telling, downplayed fears that Trump could postpone the general election, and told his donors that his team had been turning his rec room into a makeshift TV studio so he could start addressing the nation from there, starting Monday. This was the obvious topic of the day, but a supporter on the line had another question, too. What about his running mate? A week earlier Biden had publicly promised to pick a woman, but now he broke some more news: “I have to start that vetting process relatively soon, meaning in a matter of weeks,” he told the donors, adding that he’d soon look closely at “six or seven” options.

If anything, he was underplaying how seriously he’s been thinking about the decision. At the very least, he’s been understating how deeply he’s talked it through with allies in informal conversations, especially in the days since the global crisis stuck him at home. And not one of the top Biden associates I spoke with in the last week had much doubt where he would ultimately focus a lot of his eventual vetting: his former rivals Kamala Harris, Elizabeth Warren, and Amy Klobuchar. Realistically, a congressman close to the Biden inner circle predicted, no matter what happens, “the final five will include those three.”

Keeping in mind his own experience and his age, the former veep, 77, has always insisted to friends that his running mate must be ready to be president. But people close to him say he has recently become increasingly explicit that he may be choosing his own replacement, and that the candidates’ competence is now likely to be front and center in his considerations. “He’s been clear that he wants to pick someone who can be president if something happens to him,” a senior Democrat in close contact with the Biden team told me. It’s a point he’s made on recent calls with political allies, and even with his former boss. In the past few weeks, Biden has reached out to Barack Obama — who has yet to endorse him — to ask for general guidance as he pivots toward life as the nominee, tries navigating the coronavirus response, and looks for a partner, according to multiple Democrats familiar with the conversation. “I’ve actually talked to Barack about this,” Biden told his Atlanta donors. “The most important thing is that there has to be someone who, the day after they’re picked, is prepared to be president of the United States of America, if something happened.”

In chats with advisers and outside allies, he’s been loosely outlining the criteria that are now most important for him. “The reason why it worked for Barack and me so well is we agreed substantively on every major issue. We disagreed on some tactical ways to approach the issues,” Biden said on the call. (This isn’t quite an accurate retelling of their eight-year working relationship, but nonetheless a that’s-so-Joe thing to casually throw out there.) “So it’s going to be important that whomever I pick is completely comfortable with my policy prescriptions, as to how we move forward.” In private, he’s grown especially firm on this point, though when other benchmarks are brought up in conversation — like finding someone who can help him win the Rust Belt states in November — he agrees those are important, too.

Still, “I would put ‘someone who he’s comfortable with ideologically’ as number two [in importance],” said the congressman close to his team. The coronavirus crisis has elevated the main concern: “Number one is finding someone who is absolutely, undeniably ready to do the job if the unimaginable happens.” According to a handful of Biden’s close allies, this may render the case for some potential candidates who’ve never held statewide elected office — like former Georgia house minority leader Stacey Abrams, former acting attorney general Sally Yates, or Atlanta mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms — harder to make.

This instinct has been reinforced in conversations Biden has had with top allies in recent weeks, in between his check-ins with leaders like Nancy Pelosi, Chuck Schumer, and a range of Democratic governors including Andrew Cuomo about their COVID-19 response plans. Some have made their preferences clear to Biden. Schumer, who is largely concerned about Democrats’ standing in the Senate, has been talking up Harris, whose seat would certainly be safe, and, according to Democrats who’ve spoken with him, has mentioned both Michigan governor Gretchen Whitmer and Florida congresswoman Val Demings, a former Orlando police chief and Trump impeachment manager. (If Warren were chosen, Massachusetts’ Republican governor could choose her temporary replacement; Minnesota is a swingy enough state to make Klobuchar’s vacated seat a potential target for the GOP.) South Carolina congressman Jim Clyburn, whose endorsement helped revive Biden’s chances at the nomination last month, has been publicly pushing for him to choose an African-American woman. And Biden has spoken with Harold Schaitberger, president of the International Association of Fire Fighters union that endorsed him as soon as he announced his candidacy last year. Schaitberger wouldn’t tell me who he suggested to Biden, but said having “multiple experiences, in the political, legislative, and executive parts of government are the ingredients. Plus, you need someone who has the chops, the gravitas.” Both Harris and Nevada’s Catherine Cortez Masto have served in the Senate and run statewide justice departments.

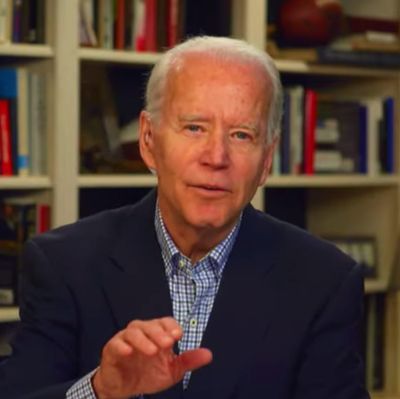

The lockdown may have also sped up Biden’s timeline while he and his campaign wrestle with their somewhat new, entirely uncomfortable reality: a likely nominee shoved far from the spotlight, with no obvious way into it. Biden’s decision to stick to Wilmington and send his Philadelphia-based campaign staff to work from home has coincided with a new campaign manager taking over his operation and trying to scale it up to general-election size, all while trying to find ways to replace Biden’s in-person fundraising and to negotiate an end to the primary against Sanders. In the last week, Biden’s team has been frustrated by the difficulty of breaking into the news cycle, fearing that offering shadow briefings to Trump’s would be perceived as overly political and might risk distracting from the work being done by Democratic governors like Cuomo and Washington’s Jay Inslee. They’ve decided, instead, that being opportunistic might be their best bet. On Monday they livestreamed a speech from Biden’s new studio, and on Tuesday he beamed into ABC, MSNBC, and CNN for interviews.

When the camera is off, though, a handful of high-ranking Democrats who have the former vice-president and his advisers’ ears have begun agitating for him to expedite the running-mate selection process in the interest of presenting a ticket that can provide a clear signal of presidential readiness to contrast with Trump, can seize the spotlight from him, and can even minimize potential chaos before the party’s convention if something does, indeed, happen to Biden. This is far from a consensus view — some allies argue that the VP rollout should be timed carefully for maximum general-election impact, and certainly not when the world is entirely focused on a terrifying virus. But the Biden team is, in fact, now at least moving toward the beginning of the process by thinking up a shorter-than-usual “long list” for the candidate to consider, earlier than they usually might. (Two of Biden’s top advisers, Anita Dunn and Bob Bauer, helped write a 2016 report recommending that candidates allot eight weeks for the process; the convention isn’t scheduled for another 16.)

Biden has hardly built a reputation as the world’s most flexible pol, especially in times of crisis, but this longish version of the list could include some unexpected names. After Biden answered the donor’s question on Sunday, the caller pointedly said she was thankful that Yates, the former acting attorney general fired by Trump in 2017, was also on the line. (“She’s really incredible,” Biden responded.) Fellow Georgians Abrams and Bottoms might also make this initial cut, as could senators including New Hampshire’s Jeanne Shaheen and Maggie Hassan, Wisconsin’s Tammy Baldwin, Illinois’s Tammy Duckworth, and governors like New Mexico’s Michelle Lujan Grisham.

But that would still be a relatively loooong version of the list. (Biden said on The View on Tuesday that in his mind it consisted of between 12 and 15 names.) Even some of the officials on that roster believe the real group under consideration would probably end up much smaller, according to Democrats close to several of them who said they were flattered, but eye-rolled at the speculation. A wide array of strategists, elected officials, and donors in frequent contact with Biden and his top advisers indeed told me without exception, and independently, that individual members of the former VP’s brain trust appeared to be more focused — informally — on Harris, Warren, and Klobuchar, with Whitmer, Demings, and Cortez Masto also likely to be in the mix.

And the behind-the-scenes jockeying has already started. Biden advisers have heard from a handful of top fundraisers arguing that Klobuchar could ensure him victory by helping him carry midwestern states like hers — an argument that has also surfaced on Whitmer’s behalf — but skeptics have pointed out that Biden’s wide Michigan win over Sanders this month demonstrated the breadth of his base there, so he likely doesn’t need that specific help. Harris detractors have offered a parallel critique of her profile, in addition to highlighting the disappointing, dysfunctional ending of her campaign: Does Biden really need the help with black voters, given his wide margins of victory with them in the primary? Still, Biden and Harris — who was friends with his late son, Beau — have remained friendly in recent months, even after Harris’s attack on the former vice-president at June’s debate. While Jill Biden expressed displeasure with the senator in private after that, many close to Biden believe her reaction has been overblown by overdramatic chatterers in the months since then. Still, some lawmakers and fundraisers who agree with Clyburn that Biden should choose an African-American woman but who are critical of Harris have been tuning in with interest to Demings’s recent television appearances (a classic tool for capturing donor attention).

Then there’s Warren, the candidate with whom Biden has had the most complicated relationship, dating back nearly two decades to Capitol Hill clashes. If any leading contender has obvious differences with Biden’s vision, it’s the Massachusetts progressive, but he told her in 2015 that if he ran the next year he would make her his running mate then. Since she exited the 2020 race, he has moved toward her on policy, and they have spoken twice on the phone, according to Democrats close to both. Perhaps the biggest question looming over Warren’s chances is how much work Biden thinks needs to be done to win over Sanders’s voters, and how useful Warren would be to achieving that goal.

That question is one reason Biden has been careful not to talk too much about this process in public, especially since Sanders could decide to remain in the race into the summer, as more primaries are delayed to June due to the virus. “We don’t want to piss off Bernie, and rushing to talk about this could end up pissing off his supporters, too,” said the congressman. “Don’t discount this concern.” Still, that concern aside, Biden is probably a few weeks away from fully addressing these worries anyway, even if he has to do so from his dining room table in Wilmington.

In a world dominated by social-distancing measures, it’s not clear to them how Biden is supposed to get to know his potential running mates, which is usually an important part of the process, and one on which Biden is likely to put an extra emphasis given his tight relationship with Obama, say those close to him. In 2016, Hillary Clinton carved out time from her busy campaign schedule to spend days on the trail with options like Warren, John Hickenlooper, Sherrod Brown, Cory Booker, and Tim Kaine (her eventual pick) even before submitting them for formal vetting or meeting the finalists for interviews at her home. Biden was only able to hold one rally with Klobuchar and one joint event with Harris and Whitmer before the campaign trail shut down earlier this month.

So for now, as he considers whittling down his list, he’s still trying to figure out how to get attention amid the crisis. On Monday, he tried using his rec-room studio for the first time. The livestream got off to an awkward start, with Biden looking off-screen and an aide audibly telling him he was live on camera. On Tuesday, he tried beaming into The View. Even then, though, the pandemic came first. His interview was delayed, preempted by Cuomo’s daily briefing.