If the 2020 presidential election becomes another tense, tight contest like the last one, with candidates battling for Electoral College votes across a complex battleground, minor-party voting could again be an important factor in the outcome. Of the many factors that led to Donald Trump’s threading-the-needle win, an unusually high level of votes for Libertarian Party nominee Gary Johnson and Green Party nominee Jill Stein is impossible to dismiss entirely, as the Guardian noted immediately after the election:

[Trump’s 12,000-vote margin was] significantly less than the 242,867 votes that went to third-party candidates in Michigan. It’s a similar story elsewhere: third-party candidates won more total votes than the Trump’s margin of victory in Wisconsin, Arizona, North Carolina and Florida. Without those states, Trump would not have won the presidency.

In part because Johnson and Stein were each running for a second consecutive time, they did very well by the standards of their parties:

Johnson (and running mate William Weld), who was on the ballot in all 50 states, won nearly 4.5 million votes; only once (four years earlier, with Johnson as the nominee) had the Libertarians topped 1 million votes. Stein and Ajamu Baraka, on the ballot in 45 states, didn’t match Nader’s enormous 2000 vote, but with around one percent of the total, they beat the previous three Green presidential tickets combined.

Both the Libertarians and the Greens will have new nominees this year who will have to work for name identification and credibility. But the bigger problem they face is the threshold challenge of ballot access, with the coronavirus pandemic complicating the task immeasurably, as Bill Scher explains for Politico:

In 2016, the Libertarian Party was on the general election ballot in all 50 states; this year, it has secured ballot access in just 35. Similarly, the Green Party—which in 2016 had its best election ever by making the ballot in 44 states, with a further three states granting the party’s candidate official write-in status—has qualified for the November ballot in only 22 states …

At present, neither the Libertarian Party nor the Green Party has qualified for the ballot in Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, New Hampshire, Iowa or Minnesota. Additionally, the Green Party has not secured a place on the ballot in Arizona, Georgia or Nevada, and the Libertarian Party is missing from Maine.

Collecting the petitions necessary for minor-party ballot access is always a chore. Getting it done during a pandemic is extremely difficult. Unsurprisingly, third-party representatives are asking states to waive petition requirements entirely (as Vermont just did, via legislation), or at least delay existing deadlines. But they also plan to go to court with a combination of traditional and pandemic-related arguments that barriers to the ballot infringe upon voting rights. Prospects for success are at best mixed, as Scher reports:

“Those kind of cases are not slam dunks because courts are generally wary of changing election rules,” said Rick Hasen of University of California Irvine School of Law, citing litigation over this month’s primary election in Wisconsin, which culminated in the U.S. Supreme Court deciding that the state could not extend the deadline for mail-in ballots because existing state law implied they needed to be postmarked by Election Day. “The Court majority was not very moved by arguments about Covid-19 being a compelling enough reason to change from the ordinary requirements of an election,” Hasen said.

“I would be shocked if the minor parties do as well in terms of ballot access this year as they did [in 2016],” said Michael S. Kang of Northwestern University’s Pritzker School of Law. He argues because of a lack of binding precedents, judges have a lot of discretion. In turn, he expects a “mixed response” with some states providing relief and others refusing to change the rules.

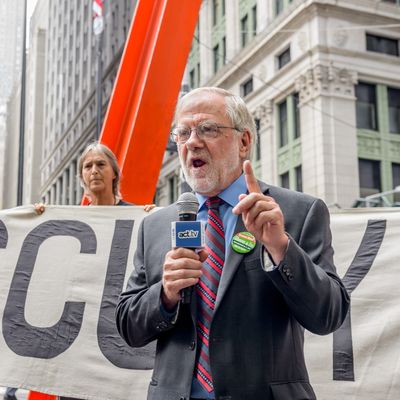

Ballot access aside, the minor parties will simply be struggling for attention during the pandemic, much like other political actors who are not in a position to command media coverage of official actions germane to public health and economic recovery. And it’s unlikely they will attract as much support as Johnson and Stein did. Green front-runner Howie Hawkins is known to some for his claim that he was the originator of the Green New Deal but is not a national figure. And the Libertarians seem to be going through a purist phase, departing from their recent practice of handing their presidential nomination to dissident Republicans like Johnson. The current front-runner, Jacob Hornberger, is committed to the very poorly timed idea of abolishing the Fed and moving to a deflationary hard-money currency.

Yes, independent (and ex-Republican) congressman Justin Amash is flirting with a Libertarian candidacy; a lot may depend on whether the party delays its May convention in Texas. Amash could raise Libertarian prospects significantly, in part because he’s from the key battleground state of Michigan and gained significant national attention by voting for Trump’s impeachment.

Ballot-access appeals by the Greens and the Libertarians could open the door for other minor parties, notably the far-right Constitution Party, which is already on the ballot in 15 states, including battlegrounds Florida, Michigan, Nevada, and Wisconsin. The best-known candidate for that party’s nomination (which will be determined by phone balloting May 1–2) is former West Virginia coal baron Don Blankenship. Most famous for a strange, more-Trumpian-than-Trump Senate Republican primary run in 2018, featuring wild charges that Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell was involved in the drug trade, Blankenship has the wealth to self-finance something of a campaign.

The relevance of any minor-party presidential candidate, of course, will depend on the dynamics of the major-party competition. Arguably a key factor in the abundant 2016 “protest vote” was the widespread belief that Hillary Clinton had the presidency in the bag. It’s extremely unlikely that opinion leaders or voters will be so confident in the outcome this time around. But crazy things can happen in crazy-close elections, so keeping an eye on the Greens, the Libertarians, and even the theocrats of the Constitution Party as the battle for ballot access unfolds would be a good idea.