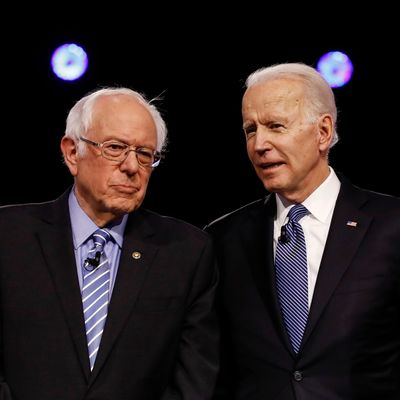

Barack Obama has been busy with phone calls since Joe Biden became Democrats’ all-but-certain presidential nominee last month. A few times, at Biden’s request, the former president and vice-president connected to talk through what comes next — how to pivot to the general election, how to campaign through the coronavirus crisis, and how to consider a running mate, people familiar with the series of calls tell New York. The former president also spoke with Elizabeth Warren about her campaign and her powerful position in the party moving forward. And he talked with Bernie Sanders more than once in the lead-up to the Vermont senator’s Wednesday exit from the race. The pair has never quite seen eye-to-eye politically, but Obama has grown to respect Sanders’s movement, and, in private, the senator has said that he takes Obama’s word very seriously. Together they chatted about what Sanders had accomplished since he first started running five years ago, and Obama made clear — as he had to Biden — that he believes it’s important that Sanders play a prominent public role in the quest to topple Donald Trump in November.

In theory, the Avengers notion of politics sounds great: a team of former rivals emerging this summer and fall to unite Democrats and save the world. But to really bring the party back together after the primary, Biden has to win over Sanders’s supporters himself, and he needs to do it against the backdrop of a horrifying pandemic, economic devastation, and a president set on stoking intraparty division. “This ended just like the Democrats & the DNC wanted, same as the Crooked Hillary fiasco. The Bernie people should come to the Republican Party,” Trump tweeted after Sanders formally ended his campaign on Wednesday.

All of which means that Biden — who has relentlessly stuck to the exact center of the Democratic party since he joined the Senate, and soon after started thinking about running for president, nearly half a century ago — has work to do. “To get as many of our supporters as possible to support and work for Joe Biden requires partnering on issues and on [party] rules,” longtime labor leader Larry Cohen, a Sanders friend and adviser who now chairs the board of the Bernie-founded political group Our Revolution, told me the morning after Sanders’s exit. “To be frank, as my great-grandmother said, ‘I’ll watch your feet, not your mouth.’ For our hardcore people, including myself, it’s not so much what Biden says. It’s what he does.”

So what’s a mainstream candidate, deeply unpopular with Sanders’s loudest loyalists, to do just six weeks after some members of Sanders’s inner circle were so optimistic about their own chances that they were informally musing about his presidential cabinet? To start, Biden is considering Warren to be his running mate, and the pair have spoken on the phone multiple times since the Massachusetts senator left the race last month. In mid-March, Biden adopted Warren’s take on a bankruptcy policy they’d previously disagreed on, then moved toward Sanders’s free-public-college position — the same one that got Bernie to endorse Hillary Clinton last time. On Thursday, about 24 hours after Sanders dropped out, Biden also announced plans to lower the Medicare eligibility to 60 and to forgive student debt for low- and middle-income attendees of public institutions and historically black colleges. Biden aides now also expect him to hire veterans of Sanders’s and Warren’s campaigns, multiple staffers tell me.

Meanwhile, behind the scenes, Biden aides have been in frequent touch with Sanders’s and Warren’s teams as well as advisers to Washington Governor Jay Inslee, who ran a climate-focused campaign last year, to talk about policy. And a trio of top Biden aides — policy director Stef Feldman and senior advisers Symone Sanders and Cristóbal Alex — spent March in conversation with progressive groups backing Sanders to hear about their priorities. On a private Zoom fundraising call on Wednesday night, a donor asked Biden how he’d engage young voters focused on climate change, and the ex-VP said he planned to more fully explain his current plans but that he’d also “directed my team to develop additional policies to add to my existing proposal. I’m committed to seeing that these good ideas, wherever I can find them on every issue, are brought into the campaign.”

You wouldn’t know it from reading Twitter, but Biden and those around him are confident about their chances with most of Sanders’s voters. For one, Sanders and Biden genuinely like each other, since Sanders believes Biden took him seriously in his early days in the Senate when few other party leaders would, and the primary never descended to the same level of bitterness as 2016’s, which also dragged on much longer, making reconciliation difficult. (In his final weeks of campaigning, Sanders regularly shushed his crowds when they started booing Biden.) And Sanders’s base of support is smaller and more reliably progressive — not simply anti-Clinton — than last time, too, while Biden’s lead over Trump in head-to-head polling has been much more consistent throughout the primary than Clinton’s was. Plus, the COVID-19 fiasco has made the stakes of Trump’s reelection clearer than ever.

The most important task in the eyes of Biden’s inner circle is to win over as many of the young voters, liberals, and Latinos who flocked to Sanders as possible, but they are also wary of angering the more prominent Bernie-backing online voices, who could hamper that progress. (What are they worried about? “I won’t vote for anyone but Bernie in the general,” tweeted one of the hosts of the Chapo Traphouse podcast in February. “Can’t say what the hundreds of thousands of people who listen to my show will do, but I’m only speaking for myself. Just something to consider.”) So Biden’s team is trying to tread carefully in public. American Bridge, one of the super-PACs backing Biden, on Wednesday started running a new digital ad featuring Biden thanking Sanders and Sanders praising Biden. After Sanders’s announcement, Biden himself issued a nearly 800-word statement that lauded his work and addressed his supporters directly: “I see you, I hear you, and I understand the urgency of what it is we have to get done in this country. I hope you will join us. You are more than welcome. You’re needed.”

Telling Sanders supporters they’re needed also reinforces their leverage. It took only a few hours after Sanders’s exit for a collective of eight groups representing young progressives and focusing on issues like climate and gun control to send Biden a stern warning shot. “Messaging around a ‘return to normalcy’ does not and has not earned the support and trust of voters from our generation. For so many young people, going back to the way things were ‘before Trump’ isn’t a motivating enough reason to cast a ballot in November,” they wrote, urging Biden to embrace a wide range of left-wing priorities, like the Green New Deal framework, Medicare for All, eliminating the Senate filibuster, and expanding the Supreme Court. “The organizations below will spend more than $100 million communicating with more than 10 million young members, supporters, and potential voters this election cycle. We are uniquely suited to help mobilize our communities, but we need help ensuring our efforts will be backed-up by a campaign that speaks to our generation.”

No one close to Biden expects him to move quite this far. But “he can’t win without the enthusiastic support of young people. If you’re a Democrat, it’s a key component of your winning coalition,” Ben Wessel, the executive director of NextGen America, one of the signatory groups, told me. And “the Biden camp knows that.” Less than a day later, it rolled out its latest health-care and education-funding proposals, both clear nods, at least, toward the left’s wishes.

For the time being, concessions like these may be the most powerful tool Biden has for wooing Sanders’s faithful. There’s never been much suspense about whether Sanders himself will support his former rival — both pledged repeatedly to back the other if they won the nomination — but Biden could use his active presence on the campaign trail, too. Sanders, after all, feeds off the energy of his massive rallies and is at his political best — and most persuasive — when he can look out at an arena full of supporters.

The problem is that no one has much of an idea right now of what that’s supposed to look like this summer, with the entire country cooped up inside. Clinton famously endorsed Obama in front of an outdoor crowd in Unity, New Hampshire, in 2008. Eight years later, Sanders backed Clinton in a packed high school gym 100 miles east, in Portsmouth, before campaigning for her around the country. This time, a livestream split between a rec room in Wilmington and a living room in Burlington might have to do.