America’s small-business sector is burning. Congress sent a fire crew to rush in and bring its occupants to safety. But to ensure that Uncle Sam didn’t send more help than was needed, lawmakers put a tight cap on the number of engines authorities could dispatch to counter the blaze. This week, that limit was exceeded. And although everyone in Congress opposes letting small businesses burn alive — and believes the cap on firetrucks should be raised — they can’t agree on the precise terms of new mom-and-pop rescue legislation. Specifically, Democrats would like to take this opportunity to also dispatch more lifeboats to America’s shipwrecked states and cities, while Republicans would prefer to let them flail about in the water a bit longer. And for the moment, the GOP has decided to prioritize letting municipalities drown over saving small businesses.

Or, in more precise (and less figurative) terms: The Paycheck Protection Program — which provides small businesses that have been adversely impacted by the coronavirus crisis (i.e., just about all of them) with forgivable loans that they can use to cover payroll, rent, utilities, and other expenses — exhausted its $350 billion reserve this week, less than 14 days after the program took effect. Republicans want to raise the cap on the program by $250 billion. Democrats would like to do that too. But they also want to send another $150 billion in relief funds to states and cities, increase food stamp benefits, and send $100 billion in aid to hospitals and community health centers. And they don’t trust their Republican colleagues to approve such funding unless doing so is the price of getting businesses what they need.

New funding for state and local governments is especially critical. Since the U.S. federal government can print the world’s reserve currency, and borrow at near-zero interest rates, it can painlessly sustain government services — and stimulate consumer demand — through deficit spending. But states and cities can’t do any of those things. And yet, they are responsible for financing and implementing the bulk of public education, policing, pandemic response, and countless other core public-sector functions in the U.S. Right now, their costs are skyrocketing as need for health-care and state-based aid programs rises, while their sales and income tax revenues are cratering as commerce grinds to a halt. If the federal government does not use its money-printing power to sustain state governments’ budgets, then they will be forced to lay off public workers and make draconian cuts to service provision — measures that will deepen the present recession and delay future recovery.

Which would be terrible for Donald Trump.

Although the president saw an uptick in approval at the onset of the crisis, so did virtually every other state and national leader presiding over the pandemic. And Trump’s boost in support was much smaller than the ones that racked up by the U.K.’s Boris Johnson, Italy’s Giuseppe Conte, France’s Emmanuel Macron, or most U.S. state governors. Now, as the economic situation deteriorates, Trump’s favorability is falling; the most recent Gallup poll puts his approval lower than it’s been in five months. These developments are all consistent with the thesis that Trump’s recent uptick in support was a product of a rally-round-the-flag effect, a common — and typically ephemeral — tendency in mass publics to grow more supportive of existing leadership at the onset of a major crisis.

Recent polling from Navigator Research buttresses this interpretation. Not only does the pollster find the public souring on Trump’s pandemic response, it also reveals that some 10 percent of voters who say they approve of the president do so more because “it is important to be supportive of President Trump during this time of national crisis” than because “Trump has shown strong leadership and taken decisive action throughout the crisis.”

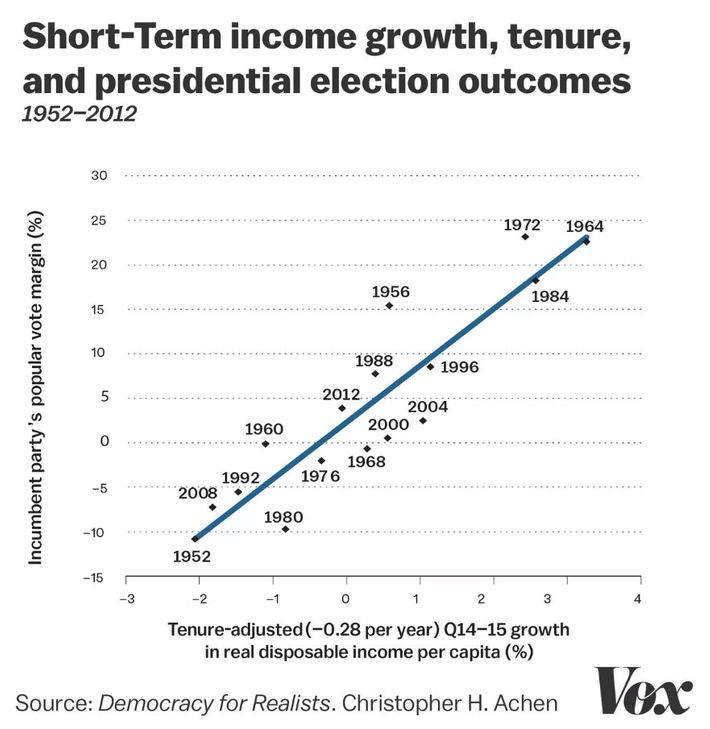

All this suggests that the long-term political impact of the COVID-19 pandemic won’t be as counterintuitive as its initial one was. Historically, swing voters turn against incumbent presidents when economic growth is weak in the second and third quarters of an election year. And there’s reason to think that Trump may be more vulnerable to worsening economic conditions than most presidents: Throughout his time in office, voters have given Trump’s handling of the economy higher marks than the man himself.

Viewed in this context, the stalled negotiations on Capitol Hill look politically surreal. Democrats want to pass legislation that will increase the odds of an economic recovery during the second half of this year and thus, Trump’s odds of reelection — and Republicans are so opposed to this idea, they are willing to risk unnecessary small business failures to avoid voting for policies that would hurt Joe Biden.

The ostensible motivation for the GOP’s behavior isn’t hard to discern. The Republican Party is the electoral vehicle of an ideological movement. When the goals of maximizing electoral success and advancing the conservative ideological project come into conflict, the GOP often prioritizes the latter over the former. This is why the party does not run figures like Charlie Baker and Larry Hogan for president despite the ostensible popularity of their brand of center-right governance. And it’s why Paul Ryan forced Donald Trump to spend his presidential honeymoon advocating for a bill that would have thrown millions of Americans off of Medicaid while eviscerating protections for people with preexisting conditions (measures so politically toxic, Ryan’s health-care bill became the most unpopular major legislation in modern history), instead of passing a bipartisan infrastructure bill that would have earned the presidential rapturous headlines and fractured the Democrats’ congressional caucus.

In other words, there has always been a tension between Donald Trump’s political interests and the Republican Party’s ideological ones. Fortunately for conservative ideologues, Trump tends to prioritize his petty resentments over his political interests (which he struggles to discern anyway), and those resentments often put him into alignment with the conservative movement.

Right-wingers would like to stand pat as pandemic-induced fiscal crises force blue states and cities to scale back the role of government. In recent years, California, New York, and other Democratic bastions made progress towards state-level social democracy, creating new universal benefits and social welfare programs. So long as Uncle Sam sits on his hands, COVID-19 could starve such “beasts” out of existence. For his part, Donald Trump has no ideological investment in seeing New York City’s universal prekindergarten program collapse. But he is personally invested in seeing Democratic governors and mayors who criticize his administration suffer. Thus, he’s had few complaints about Republicans obstructing aid to hard-hit blue states (or hard-hit red ones, for that matter).

Trump’s deep-seated instinct to punish his critics may have its political uses in some contexts. But the context of an election year pandemic-induced recession is not one of them. Republican strategists have voiced fears that the COVID-19 catastrophe could hurt the president in key swing states with significant outbreaks, like Wisconsin and Florida. But when economic disaster strikes in New York, it does not stay in New York: In 2018, the Big Apple was responsible for nearly 5 percent of all economic growth in the United States. And the deep-blue urban centers of New York, California, and Massachusetts collectively produce a wildly disproportionate share of U.S. GDP. You cannot let these places all simultaneously fall into fiscal crisis and have your midsummer economic recovery too.

Congressional Republicans can stop sabotaging Trump’s reelection campaign without totally capitulating to Democrats. For example, Mitch McConnell could offer the “concession” of funding for states and cities, hospitals, the Postal Service, and hazard pay for frontline workers (all measures that would strengthen the economy) — but also insist on heaping a couple more tax cuts for rich people on top. Instead, the GOP has chosen to prioritize devastating America’s economic centers in a manner that will help Joe Biden win the White House.

And Donald Trump is letting McConnell do this — because America’s greatest con man is also, apparently, its biggest mark.