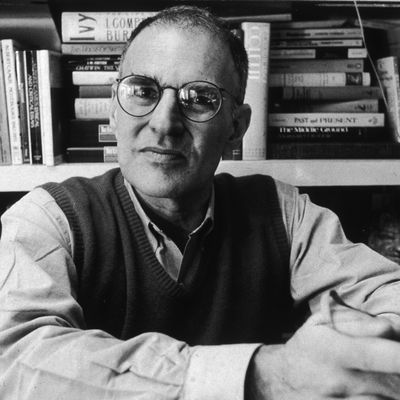

The last word you might associate with Larry Kramer is sweet. But he often was. We first met decades ago in a leather bar on the old West Side Highway, where he berated me for reasons I can’t quite remember now. We also talked at length on the record 25 years ago, when I interviewed him in his apartment in New York City for Poz magazine, while the plague still raged.

I remember he treated me like a wayward child who needed to be loved, goaded, and guided. We shared contempt for Washington, D.C.’s gay Establishment, and for the way so many gay men — out of shame or fear or cowardice — refused to exercise the power they actually had. We differed in our views of how to win over the public. He favored aggressive provocations; I preferred reasoned dialogue, both because I’m an old-school liberal who believes in reason, and because I believed we had the better arguments. Both approaches, of course, were necessary — but Larry was never going to do the latter. And disrupting Masses by desecrating hosts in Saint Patrick’s Cathedral was not, as one might say, my bag. Larry was proudly hostile to, but also intrigued by, religion, and, like Christopher Hitchens, constantly razzed me for it.

But always affectionately. For every unexpected harangue, there was an unexpected Valentine. “Happy new year etc, old mate, babe, kid, fellow toiler in the vineyards, whatever. Xxxxx,” he once emailed me out of the blue. And another: “We have been through so much together, you and I, separated though we may be by cities and other things. I always think of you as a comrade in arms. And I remember when we first met in the Spike or some NYC gay bar and I thought you were so very very cute, handsome really, and lusted after you! Onward, both of us!” As I said: privately sweet, publicly ferocious. Too few saw the sweetness, or the pain that lay behind it, the wounds in his family, the loneliness of his past.

I admired him because he refused to let gay men off the hook. He didn’t pander. He made no excuses. He didn’t preach to the choir, as so many victimologists do; he screamed at it, partly because he knew how to do that and partly out of frustrated love. So many he came of age with were still riven with self-hatred; they were, in Larry’s view, having too much meaningless sex, because they had internalized a lack of self-worth; they were too quick to please those in power; they were “faggots” as his first novel brazenly declared — lacking the nerve or integrity to become fully realized human beings. “I hope I want for them what they want for themselves, which is to be equal,” Larry told me simply all those years ago. “We don’t have the rights we deserve and we have to look first to ourselves to see why, rather than blame an obviously culpable system.” Yes, he believed the system was rigged against us, but he also saw the unique potential of taking direct and personal responsibility to “unleash power” and change the world.

He was never going to join a pity party about homophobia: “I was a really miserable child. I tried to kill myself when I was very young and I’ve had a zillion years of therapy and I was very shy and withdrawn and I wanted to write and I couldn’t write and it seems to me that I’ve been able to pull myself together and climb a lot of mountains that I’ve wanted to climb. And I guess I figure that if I can do it, a lot more people can do it.” So he berated them, outed them, harangued them, and also inspired them to get their asses off the couch and do something, especially when our very lives were on the line.

Although his message was uncomplicated, he wasn’t. “I don’t know whether I’m radical or traditional or conservative. It depends on the day, it depends on who’s looking at me.” I’d say he was a radical conservative. He wanted gay men and women to have the same opportunities and self-respect as straight men and women. And he couldn’t understand why others didn’t share the urgency of this simple vision. He simply refused to be condescended to. Immune to ideology while addicted to absurd hyperbole, he was obsessively focused on getting things done, even as, it must be said, he sometimes made that more difficult rather than less, by his obstinance or anger or refusal to let a grudge go. And he was absurdly crude in some of his judgments.

He publicly insisted that men like Anthony Fauci were genocidal murderers and viewed every single president as homophobic. I just saw this in my email archive, where “Ned Weeks” would routinely pop up, with some new provocation: “President after President have treated us so badly. Ronald Reagan. George Bush the first. Bill Clinton. George Bush the second. Barack Obama. They have all treated us like … shit. Like little pieces of shit that they can step on with their heels and grind into the ground. Obama is treating us just like that.” Okay, Larry. I get your point. But … this isn’t entirely true and isn’t entirely helpful. But nuance was not Larry’s métier. I remember vainly trying to get him to concede that there was a difference between murdering someone, and being somebody nearby who didn’t stop it from happening. But it was a hopeless task. For Larry, they were always equally to blame.

He was, literally as well as figuratively, a drama queen, but the title of his polemical play, The Normal Heart, revealed something deeper. He saw the homosexual experience as essentially one of love, rather than sex. He thought of it as normal, as something that should be fully integrated into the family and institutions. The only other person with this moral clarity that I had come across at the time was the historian John Boswell, and both helped me see the full worth of the homosexual contribution to our world.

I think Larry was too hard on sex, and failed to see how gay men had managed to turn what some call promiscuity into a form of intimacy and adventure that need not exclude love or eventual commitment. But I think he also saw some of the desperation in that constant search for the next nut, and was saddened by it. Like Randy Shilts, he believed that AIDS in any respect changed everything, as of course it did, and raised the alarm. They were both right, much earlier than anyone else, and both were viciously vilified and smeared by other gay men for it.

When I asked him why he had made so many enemies among gay men, he quipped: “Well, the same could be said about you.” “Well, I don’t think people know what to do with me,” I answered. “That’s like me,” he replied. “They think we only have one schtick.” And, yes, Larry didn’t just have anger; he also had compassion, and grace, and a vision of homosexuality that was noble, honorable, esteemed, erudite, respectable. Like me, he was convinced, for example, that Abraham Lincoln was gay, and that Lincoln needed to be revered in gay history alongside Whitman and Newman and Wilde and Auden. Another email came in the wake of some comments I made on the subject: “Thanks for the gay Abe Lincoln plug. But he did not sleep with Captain David V. Derickson, of Company K, 150th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteers, Second Regiment, Bucktail Brigade in the White House when Mary was there. Only when she was away!” (If you’ve never considered Lincoln’s quite obvious homosexuality, check out this book.) He was more into Whitman than Drag Race, more concerned with Turing than the gym, more interested in Keynes than a circuit queen. In fact, there were so many trivial and silly aspects of gay culture he despised.

And he never lost the psychic energy, or the drive for respect. “I had a sneaking feeling we’d get along,” I said to him all those years ago. “I never had any doubt or I wouldn’t have done this interview,” he replied. “They just say terrible things about us. I guess it’s one way of knowing you’ve done something right. Joe Papp [of New York City’s Public Theater] used to often say that people don’t remember anything except that your name was in print. In the end, it does not make a bit of difference. You’ve got to keep it going. We have the energy; that’s what we have. We’re not lethargic. The secret, Andrew, is sugar.” May the God he didn’t believe in bless him and embrace him and love him as deeply as he deserves.

California’s SAT Mistake

Last week, the University of California system’s Board of Regents unanimously ruled that the most prominent higher education system in the country will continue its suspension of SAT testing for admission. (It first suspended them this year because of COVID-19.) This follows an 18-month process in which a thorough study was conducted by UC itself into whether the SAT was being unfair to what they call “under-represented minority students,” a term that includes black and Latino students but excludes Asian-Americans, a group once brutally discriminated against in California in particular. The study found that scrapping the test could actually worsen the chances of smart black and Latino kids from poor backgrounds getting into UC.

Yes, you read that right. You can read the study here, as I did. It’s an exhaustively thorough review of the evidence, conducted by serious academics concerned that UC’s student body doesn’t mirror the racial demographics of the state as a whole. UC president, Janet Napolitano, claims that UC will come up with some kind of alternative admissions policy that “more closely aligns with what we expect incoming students to know to demonstrate their preparedness for UC.” I don’t know what that means, but it suggests that students will have to provide evidence of knowledge rather than intelligence to be admitted — which seems like it would favor those from better schools in better neighborhoods. A smart kid ill-served by a bad school? She might be less likely to get in.

In this, the UC study felt no need to relitigate the no-win arguments over the source of these resilient differentials in SAT scores, the nature of intelligence, or the power of social structures to sustain group differences. They set all those explosive matters aside — rightly — to focus on a paradox that even many liberals have come to accept: that the SAT, for all its faults, may be the most effective way — or least ineffective way — of actually ensuring racial diversity, without lowering standards. Scrapping it could make things worse for gifted and poor black and Latino kids, who are often deprived of good schooling, but who use the SAT as their primary way of counteracting their socioeconomic or cultural disadvantages and proving their potential. It appears to be the most effective way of finding these kids. More to the point, the UC study found that a full 47 percent of the students who were admitted because of their SAT scores “were low-income or first generation students. These students would not have been guaranteed admission on the basis of their grades alone.”

The SAT isn’t perfect, of course. But it has been finessed over the years to be more and more predictive of ultimate success in college and beyond. The UC system may try and find a better metric to use, but its own report found that at UC, “test scores are currently better predictors of first-year GPA than high school grade point average (HSGPA), and about as good at predicting first-year retention, UGPA, and graduation. For students within any given (HSGPA) band, higher standardized test scores correlate with a higher freshman UGPA, a higher graduation UGPA, and higher likelihood of graduating within either four years (for transfers) or seven years (for freshmen).” High-school grades — subjective, varying greatly across schools, and often diluted by runaway grade inflation — are far more unreliable.

Here’s the kicker: “Test scores are predictive for all demographic groups and disciplines, even after controlling for high school grades. In fact, test scores are better predictors of success for students who are Underrepresented Minority students, who are first-generation, or whose families are low-income.” My italics. Think about that for a moment. The SAT — according to UC itself — finds poor kids from unrepresented minorities who really will succeed in college, and who won’t drop out, better than any other measure. Why is that a problem rather than a success?

You could argue that selecting students most likely to succeed in college is not the only job of a university; and you’d be right. But the alternative — selecting students who you know are more likely to fail — is unfair to everyone. For every student who will benefit from scrapping the SAT, there is another one who will be denied the opportunity — and the impact will be hardest, the study shows, on low-income and first-generation students. UC, moreover, takes great care to supplement the SAT with much more context for each applicant, what they call a “comprehensive review,” checking for family background and the quality of schooling to account for any obvious extra hurdles. The UC study found that “UC admissions practices compensated well for the observed differences in average test scores among demographic groups.”

They’ve been working on this for years, and obviously care a huge amount about minority representation. But even if you do all this, most black and Latino students still fail to do as well as whites and Asian-Americans. The study’s authors believe that this is largely due to what they call “systemic racial and class inequalities that precede admission: lower high school graduation rates for URMs, lower rates of completion of the A-G courses required by UC and CSU, and lower application rates. The most significant contributor was lack of eligibility as a result of failure to complete all required A-G courses with a C or better.”

Napolitano appears to believe that students who couldn’t maintain C grades in high school, in an era of gross grade inflation, and have low SAT scores, might thrive once they get to college. Her own report refutes her: “For any given high school GPA, a student admitted with a low SAT score is between two and five times more likely to drop out after one year, and up to three times less likely to complete their degree compared to a student with a high score.” Does she want her university’s dropout rates to soar? If UC develops some other kind of test, it will only avoid this if that test closely matches the SAT. Which kind of defeats the purpose, don’t you think?

There’s a note in the study that says, “It is ironic that the SAT was developed during the early part of the last century for the purpose of identifying intellectually talented male students without ties to the nation’s elite families, or who resided outside the closed circle of prep schools in the Northeast.” But it isn’t ironic. The SAT was once a progressive idea and it worked to extend opportunities far beyond what was possible at the time. It opened up education for millions and still does — as the extraordinary success of new Asian-American immigrants attests, and as the domination of women in college today proves.

In Britain, it was the socialist government of 1945 that initiated a version of this for high schools to find bright kids from poor backgrounds who could supplement and replace the old elite. But the left was grounded then in a different idea of social justice: an attempt to ensure that class and race would not be obstacles to individuals who wanted to fulfill their potential. Today’s left — consumed with the idea of group equity — has a different view.

The Honeymoon Is Over for Boris Johnson

Dominic Cummings is a man almost designed to be despised. The key thinker behind Boris Johnson’s Brexit strategy, stonking Commons majority, and new Red Tory agenda is indifferent to abuse, and in many ways, appears to enjoy it. He loves to tweak the Establishment and joust with the press, has an element of Steve Bannon–style nihilism to him, shuns the limelight, hates the bureaucracy in Britain, and summons up all kinds of hysteria on the British left. And now, he has enraged a large swathe of the right as well.

An architect of Britain’s punitive lockdown, he was caught breaking it, and the battered Brits, with the highest excess death rates per capita in the world, unleashed all their pent-up frustration and fury at him. You can get lost in the weeds of his transgression, and the details matter, but the story is basically this: He and his by-then sick wife both assumed they had caught COVID-19 and they have a 4-year-old, whom they worried about. What if they both got too sick at once to care for him? So they took the boy on a 250-mile journey to Cummings’s parents’ estate, stayed in a separate house on the property, and had the kid looked after by family members, while the Cummings couple recuperated. And the rules of the U.K. lockdown forbid this. They should have stayed in place, and sought local help. There were exceptions built in, specifically with respect to caring for young children, but, as a member of the government, Cummings should probably have set an example. Or at least asked the prime minister for permission.

I’d be reluctant to throw a stone at someone in that situation — a vulnerable kid and a horrible infection — and he might have been forgiven for that alone. But he also took another previous trip of around 30 miles to a beautiful landmark with his wife on her birthday. He justified this as a way for him to test his eyesight — COVID-19 can skew the vision — before he took his kid on the long journey. This argument, frankly, seems more than a stretch. And so it seems clear that he broke the lockdown in letter and spirit. When you are the most powerful figure in government, that’s a no-no. Polls show that 59 percent of Brits think he should resign or be fired.

But, at this time of writing, he’s still in place, and Johnson’s defense of this rule-breaking has taken its toll. The Tory lead over Labour has gone from 16 percent to 9 percent in one week; Boris himself had a plus-25 percent rating very recently, and now is 2 percent underwater. General public outrage has been greeted with a frenzy in the mainstream media, right and left, which have long been spurned by the extremely elusive Cummings, and are merrily exacting revenge.

And Cummings has refused to say sorry. In a long press conference, he came across as far more modest and unassuming than his public caricature would suggest, but cited technicalities in his own defense, which is not something an anti-elite populist can credibly do. And, in defending himself, he has ruined the key argument that the Tories have recently had: that they are more in touch with normal people, including working-class people, than Labour. Suddenly Johnson and Cummings have become symbols of the opposite: elitists who make rules for everyone else that they personally have no intention of obeying.

But for all this damage, Boris has stuck by his man. And that, perhaps, is the most revealing tell of this entire episode. It makes plain that without Cummings, Boris doesn’t really know what to do. An opportunist, he was smart to attach himself to Cummings’s populist cunning, but it’s unclear whether Boris fully believed in the agenda his guru set — a shift left on economics, a shift right on culture and nationalism — or whether he was, as usual, winging it, and without his Dom, he has no clue. And Boris now has, for the first time, a serious opposition leader, Keir Starmer, able and willing to skewer the prime minister over his failure to shut down soon enough, his scattershot approach to reopening the British economy, and the appalling toll the virus has taken, particularly in care homes. Boris’s luck has finally run out.

And, to be honest, I think that’s a good thing. We need good opposition, especially when a government has bungled a public-health crisis. The Tories’ huge lead has led to a certain complacency which needed to be punctured. Cummings is still in place to keep Boris on the same populist track, but the Johnson honeymoon is over. This is not the moment his government collapses, as some have hyperventilated this week. He has, after all, just been elected, and has almost five more years until the next election to recover. But it’s a sign that the elite Boris’s anti-elite shtick is, shall we say, fragile.

See you next Friday.