Five months ago, America’s unemployment rate was at a half-century low, wages were rising, consumer confidence was high — and Donald Trump’s approval stood at about 43 percent.

Since then, more than 30 million Americans have lost their jobs, the U.S. economy has descended into its worst crisis since the Great Depression, a (still-uncontained) pandemic has killed 80,000 Americans, the president has advised voters that they may be able to cure themselves of the coronavirus by injecting bleach — and his approval rating now stands at about 44 percent.

This seems unsustainable. For weeks, my working assumption has been that COVID-19 would enfeeble the Trump campaign eventually. Throughout Trump’s presidency, voters have evinced higher approval for his economic management than his overall job performance. And in 2016, Trump’s personal unpopularity caused him to perform worse than a generic Republican would have been expected to, given the “fundamentals.” So there’s long been reason to think that a (relatively) strong economy was keeping Trump’s poll numbers afloat: If a pathological narcissist with no message discipline was running a tad behind Joe Biden when unemployment was historically low, surely he would fall out of contention once America entered a pandemic-induced depression.

That still sounds right to me. Given the administration’s refusal to avert state-level fiscal crises and its failure to mount any real plan for preventing a second wave of coronavirus infections, life in America is poised to get worse before it gets better. Trump did see a polling boost in the immediate aftermath of the coronavirus outbreak, but so did every other leader of a stricken state or nation. Electorates tend to rally around their leaders in times of crisis. But this deference to authority is usually temporary and contingent on good performance. And even at its peak, Trump’s boost was much smaller than those of the average foreign head of state or U.S. governor. Eventually, reality asserts itself.

And yet: We’re more than one month into America’s worst economic crisis in 80 years and Trump’s approval rating is still considerably higher than it has been for most of his presidency.

Meanwhile, in some surveys, voters still give Trump’s handling of the coronavirus higher marks than his overall job performance. And a Reuters/Ipsos poll released last week found Trump in a statistical tie with Biden on the question of which candidate would be better at leading America’s coronavirus response, while voters deemed the president “better suited to create jobs” by a margin of 45 to 32 percent. To be sure, approval of Trump’s handling of the pandemic is trending down in most surveys. But it isn’t acting as an anchor around his overall popularity yet.

Biden’s lead in national polls remains formidable. There’s scant chance that Trump will receive more votes than his Democratic rival this fall. But, of course, he won’t need to: Due to the overrepresentation of heavily Republican, white, non-college-educated voters in battleground states, Biden will likely need to win the popular vote by roughly three points to secure an Electoral College majority. Further, as the New York Times’s Nate Cohn notes, most national polls are of registered voters, not likely ones. And since the GOP’s older voting base still turns out more reliably than the Democrats’ younger one, “a reasonable estimate is that Mr. Biden is performing four or five points worse among likely voters in the critical states than he is among registered voters nationwide.”

Biden’s lead among registered voters nationally declined slightly over the past week and now sits at 4.4 points in RealClearPolitics’s polling average.

For Democrats, none of this is that concerning so long as one posits that Trump’s crisis halo is in the process of wearing off and the well-established correlation between economic conditions and incumbent approval will soon resurface. But what if that correlation is an artifact of a less polarized time in American politics?

Over the past two decades, U.S. voters have become ever-more-tightly ensconced in one party or the other. Ticket-splitting — the practice of voting for one party at the presidential level but another down-ballot — has plummeted since Barack Obama’s election. This has reduced the importance of many nonpartisan variables in electoral outcomes; a decade ago, the advantage of incumbency in Senate elections was more than twice as large as it is now. There’s reason to think that these developments aren’t aberrations produced by the odd circumstances of a few election cycles but rather reflections of structural changes in the American media landscape. Political scientists have found that when a given region first secures broadband internet access, its residents increase their consumption of reporting from partisan news outlets. Today, Americans are getting more of their information about politics from national, ideologically oriented outlets — and less from local, putatively neutral ones — than ever before. In this context, it would make sense for variations in the quality of down-ballot candidates, or the strength of local economies, to exert much less influence on voter behavior than they have heretofore.

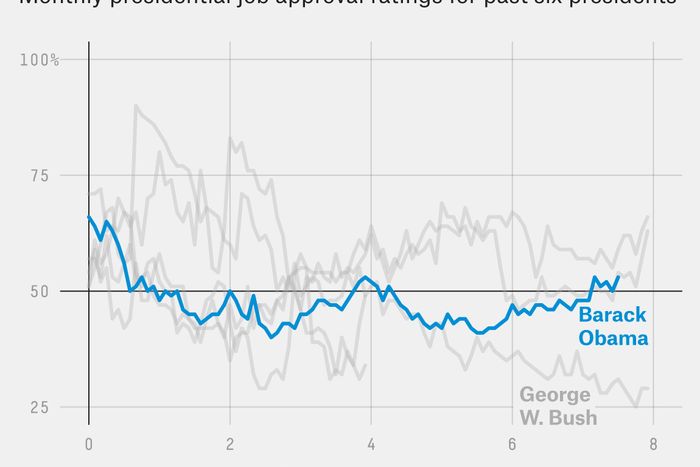

And, as a matter of fact, there was no tight correlation between Barack Obama’s approval rating and the performance of the U.S. economy during his time in office:

Which is to say: Unprecedented conditions were already rendering the laws of political physics unreliable before the worst pandemic in a century hit our shores. The cause-and-effect relationship between economic performance and incumbent popularity was already falling a bit off-kilter. This does not mean that we should reject a premise as intuitive and historically validated as “if America descends into a depression, voters will punish the party in power.” But it does mean that we can’t take it as a given; or at least, we can’t assume that the penalty Trump will pay for the worsening economy will outstrip his structural advantages. In a world with fewer swing voters, a recession is likely to hurt Trump less than it would past incumbents. And Biden can win 3 percent more ballots this November and still lose the presidency.

Counting on the universe to give Donald Trump what he deserves may not be the safest bet.