A few weeks after every presidential election since 1972, leaders of the winning and losing sides have gathered at Harvard to hash out what, exactly, just happened. In 2016, there was a lot to yell about. The retelling of the campaign devolved into a highly tense two-day finger-pointing session capped by one senior Hillary Clinton adviser’s volley, “I would rather lose than win the way you guys did.” “That’s why you lost,” replied Donald Trump’s first campaign manager. “No, you wouldn’t,” added his second. The fireworks obscured the actual competing theories about Trump’s victory, including the one quietly offered by Clinton’s campaign manager. Robby Mook revealed that, by his reckoning, Clinton would have needed to win at least 60 percent of young voters — an outcome that had appeared likely until that fall. But late-stage disengagement and third-party candidates stepped in and pushed her number down into the 50s among this group, he said, and “that’s why we lost.”

Three and a half years later, as American streets fill nightly with young protesters, no one can quite agree on where Joe Biden stands. Is he running ahead of Clinton among the youngest voters owing to their hatred of Trump — and therefore even more securely buckled into the electoral driver’s seat than widely assumed? Or is Biden lagging dangerously behind Clinton’s pace — far enough back that he needs to significantly retool his youth outreach to beat Trump, no matter how unexpectedly strong his position may be among traditionally Republican groups like older voters and suburbanites? And, most urgently, have the recent weeks of unrest simply served to highlight the vast divisions between Biden and Trump — whose unacceptability to younger Americans deepens by the day — or are they instead underscoring a significant disillusionment with all politics, in particular among young black voters, that could spell trouble for the Democrat?

The confusion is understandable: One CNN analysis of national polling in April showed Biden roughly ten points short of where Clinton was among 18-to-34-year-olds after he was routinely destroyed by Bernie Sanders among this group in the primaries. But the well-respected Harvard Institute of Politics’ poll of 18-to-29-year-olds released a few days later placed Biden right around the 60 percent goal Mook had mentioned, and the former vice-president has consistently led national polls of the entire electorate. Plus, while many Democrats are worried that the protests show young voters ready to make a significant break from voting as a tool of politics as usual, others are convinced they are actually energizing this group to become further involved — usually pointing to the voter-mobilization groups boasting blockbuster registration numbers in recent days.

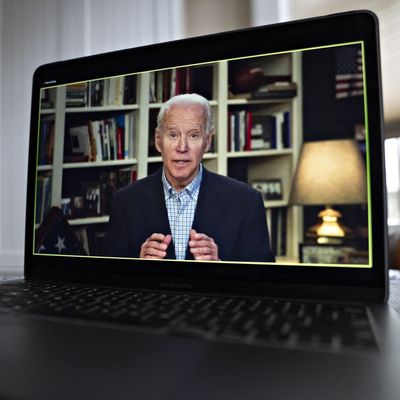

This ambiguity has led Democrats to their strategically safest conclusion: They might as well step things up. So in recent weeks, Biden ramped up his digital-outreach hiring and announced the launch of a new, discrete effort within his campaign to marshal resources specifically around organizing young voters. He’s appeared on new kinds of platforms for him, like Megan Rapinoe’s Instagram Live and with Don Cheadle on The Shade Room, while party groups focused on youth turnout, like the Tom Steyer–funded NextGen America, have formally begun orienting more of their programs toward electing him. And, as the protests over the police killing of George Floyd have grown, those close to Biden have been considering calls for him to directly address his involvement with the 1994 crime bill as a way of engaging young black voters about his own growth, and assuaging their concerns. (One Wilmington youth pastor last week urged Biden to do so directly; Stacey Abrams, a potential Biden running mate, soon after told me, “If that is what young people need, then that is what they should have.”)

If that’s hardly enough for Democrats — who saw their primary as a huge warning sign about youth turnout, and the ongoing protests as a set of ringing alarm bells — people close to the Biden camp insist it’s at least an adequate start, considering the surprisingly encouraging shape of the candidate’s coalition apart from young voters. Trump won voters over 65 years old by seven points in 2016, and Republicans have relied on that hyper-high-turnout group for years. But recent public and even private GOP polling has put Biden ahead by at least ten points with older voters — even before the coronavirus pandemic placed this highest-risk demographic in the spotlight. That alone is enough to significantly change both parties’ November calculus, since these voters are a bigger part of the electorate in the six main battleground states, and especially in Florida and Arizona, than in the country as a whole.

Many strategists close to Biden and his team see in these shifts a continuation of trends revealed to dramatic effect by the 2018 midterms, when Democrats’ gains, particularly in the suburbs, were enough to win back the House. In close statewide races, where young voters were energized but older ones remained more skeptical about the Democrats, Republicans tended to win, these strategists often note — pointing specifically to the Florida gubernatorial race that saw Andrew Gillum fall to Ron DeSantis. However, they add, when middle-of-the-road Democrats were able to activate young voters while competing seriously among their older counterparts, they were successful: Just look at Arizona, where Kyrsten Sinema narrowly won Jeff Flake’s old Senate seat using that playbook.

The members of this crowd acknowledge findings like the ones circulated recently by NextGen and the Democratic Global Strategy Group, showing that young voters still don’t know much about Biden and view him as a typical old-school (and old) politician. But they are convinced this is fairly easy to fix. It’s often as simple as publicly comparing Biden’s record to Trump’s, they believe.

That’s roughly where the optimism hits its limit. Senior Democrats see that the youngest voters clearly prefer Biden to Trump, but they still need to organize them to actually vote for the man who, according to CNN’s analysis, won only 16 percent of Democratic primary voters under 30. “A lot of Biden’s support [among young voters] is soft support, so he has to shore up youth support, but also make sure to target all the people who say they don’t know and might vote third party,” explained Ben Wessel, the executive director of NextGen, which endorsed Biden in May and has pledged to spend $45 million this year. “What’s really clear is that Trump has a ceiling of about 33 percent with these folks — I don’t think there’s any risk they’re going to go to Trump. [Democrats] just have to make sure they’re going to Biden.” Now, especially amid the protests, senior Democrats have identified this task as a top priority for Biden — many believe he needs to work hardest to reach black and Latino Americans who feel disengaged from politics and not just the ones who supported Sanders in the primary.

In late May, the Biden team announced steps it would take toward these ends, forming an effort it calls “League 46” to bring the campaign’s various youth-outreach strands under one umbrella hoisted by senior adviser Symone Sanders. The idea is to have a centralized hub for the campaign’s youth organizing and also to mobilize surrogates, including young lawmakers and activists, to expand Biden’s network with youth voters through events like Zoom happy hours. Already, organizers have held a handful of virtual brunches for young battleground-state voters that are focused on specific topics, like policies to support minority-owned small businesses.

Still, some of the usual tools for organizing students may be of limited use in the coming months if colleges begin the fall semester virtually. Wessel, whose group has a major presence on swing-state campuses, pointed out that most students would still likely be in the states where they go to school, but at home. That makes messaging to large groups of students at once trickier, and Democrats are making plans to be as present as possible on the virtual versions of those quads and dorms: “There are so many campus-based meme pages where you can spread content dedicated to people usually on those campuses,” he said. He cited the University of Wisconsin at Madison as an example: The “UW-Madison Memes for Milk-Chugging Teens” Facebook group has nearly 28,000 members; the school has around 32,000 undergraduates.

Meanwhile, the Biden camp itself has so far been tentative about its digital outreach to young voters, wary of looking like it’s pandering and conscious of the need to target its messaging to relevant media. “Everybody hears ‘digital’ and goes, ‘Young people!,’” Biden’s digital director Rob Flaherty told me in May. “The plurality viewer of our videos on Facebook is a 65-year-old woman. We think about different platforms differently.” Biden himself has stepped only gingerly into such targeted outreach — he and his wife, Jill, joined the soccer star Rapinoe’s Instagram Live in April because her audience includes many young women voters, for example — even as he admitted to Snapchat’s Peter Hamby this spring, “I’m sure we can do better on the internet; I’m positive of that.” Internally, Biden’s senior aides have been vetting possible appearances and content by asking if it will be a chance to focus on the message of decency, empathy, and connection to real people, which they believe are the former VP’s best attributes to communicate online. “The big, big thing is we don’t win voters by doing goofy, stunty shit,” said Flaherty, who, like others in Biden’s orbit, is inundated by constant demands from well-meaning middle-aged supporters that the candidate appear on TikTok. “We win young voters by treating them like voters and taking their issues seriously.”

But the bulk of Biden’s work to win this group over has so far come through traditional campaign channels, which is how he’s tried to appeal to skeptical Sanders backers since the Vermont senator exited the race in April. Members of Biden’s inner circle are convinced he is in better shape with former Sanders voters than Clinton was, in large part because of how quickly the primary ended, but they have nonetheless spent more time trying to bring Sanders backers into the fold than many expected would be necessary.

This has largely involved policy outreach. Shortly after Sanders dropped out, a coalition of eight groups representing young progressives sent Biden a letter arguing that he needed to stop messaging around a return to normalcy and pushing him to make drastic policy changes toward the left on a wide range of issues.

It’s all in keeping with Sanders’s public push for Biden to focus on young voters. In the days leading up to the launch of League 46, Biden campaign officials reached out to a handful of progressive groups like the environmentally focused Sunrise Movement and the gun-safety group March for Our Lives to discuss collaborations. “The core message here is: This election is about working people, it’s about the future of the planet, as opposed to two personalities. And if we look at the race in that context, it becomes a much more exciting time for those young people,” said Jeff Weaver, the longtime Sanders adviser now running a super-PAC dedicated to getting Sanders fans behind Biden.

Biden is hoping to rely on Sanders’s direct help campaigning in the summer and fall, too, and now, said Symone Sanders (no relation to Bernie, though she worked for him in 2016), outreach to the Vermonter’s voters “is a core part of what we’re doing. But we don’t wall it off and say, ‘This is our engagement of former Bernie or former Warren voters.’”

What Democrats are still divided on is how explicit that appeal will need to be this summer and fall, especially while Biden and his operation figure out how to ramp up in-person events while remaining mindful of the pandemic. “One of the problems is many of his surrogates who are much more popular with young people cannot go out and do things they would otherwise do,” said Weaver, who helped organize Sanders’s general-election campaigning for Clinton in 2016. And that means nervous activists, strategists, and backers alike have recently been bombarding everyone in Biden’s circles with suggestions even more than usual. (“If one more donor asks me about TikTok …,” one operative working on youth turnout grumbled to me last week, his voice trailing off in frustration.)

Not that the Biden camp always thinks such advice is wrong.

On the last Thursday in May, after a few days of sniping between Biden and Trump about the wisdom of wearing a mask in public, the Washington Post’s followers on TikTok saw the paper’s latest upload. The 18-second video begins with Dave Jorgenson, the Post’s TikTok host, walking his dog and loading an episode of Biden’s podcast. Instead of the expected programming, though, Jorgenson hears Biden himself through his AirPods: “Dave, what the hell?,” Biden asks. “I told you to wear your mask outside.” The former VP then talks to Jorgenson directly through his phone: “Yeah, Dave, it’s me,” he tells a baffled Jorgenson. “You need to wear your mask outside, I don’t care if you’re just walking your dog.” Jorgenson puts on a mask and Biden sighs: “He’s never gonna learn.”

The appearance came after weeks’ worth of brainstorming. “If you were to have the VP show up and do the Renegade or whatever, that would backfire. We took a lot of time to think, ‘What is the way to do TikTok that is substantive, on brand for him, and allows him to be the version of himself that has, historically, resonated with young people?,’” Flaherty explained. “And we landed with this—the Washington Post, an institution we all know, on TikTok, with viral reach. And a mask PSA with Joe. That’s the sweet spot.”