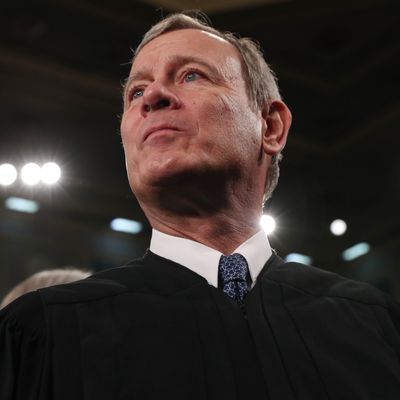

A day after he dismayed cultural conservatives by writing an opinion for a 5-4 majority that struck down a restrictive abortion law in Louisiana, Chief Justice John Roberts rejoined the Supreme Court’s right wing in a major church-state case. Writing for a conservative 5-4 majority in Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue, Roberts overruled a Montana Supreme Court decision that killed a state aid program for children in private schools on grounds that it violated a state constitutional prohibition on public aid for religious activities. That prohibition, wrote Roberts, violates the First Amendment’s Free Exercise of religion clause insofar as aid was denied students strictly because they attend religious schools. “A state need not subsidize private education,” Chief Justice Roberts wrote. “But once a state decides to do so, it cannot disqualify some private schools solely because they are religious.”

Roberts’s opinion sought to chart a path between the Free Exercise and Establishment clauses of the First Amendment, expanding the narrow argument he made in 2017 in a case involving a Missouri program for playground improvements that collided with a state constitutional provision similar to Montana’s. There, too, aid was made available to all schools, public or private, other than religious schools. But Roberts took care to distinguish both situations from a Washington State decision to disqualify a student pursuing theological training from a scholarship program, which the Court upheld in 2004.

At least three of Roberts’s fellow-conservatives weren’t that enamored of the distinction he drew between discrimination based on religious status (impermissible) rather than religious acts (permissible). Justice Clarence Thomas doesn’t believe the Establishment Clause applies to the states at all. Justice Neil Gorsuch supports broader protections for religious activities. And Justice Samuel Alito penned a long concurrence making the point that state constitutional “no-aid” provisions like Montana’s (and Missouri’s) are a legacy of 19th century anti-Catholic bigotry.

The four liberal dissenters weren’t entirely in accord, either. Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Sonia Sotomayor argued that by shutting down the entire private school scholarship program Montana eliminated any grounds for a religious discrimination claim. Justice Breyer took issue with Roberts’s claim that the schools in question were being excluded from the scholarship program because of religious status rather than activity:

If, for 250 years, we have drawn a line at forcing taxpayers to pay the salaries of those who teach their faith from the pulpit, I do not see how we can today require Montana to adopt a different view respecting those who teach it in the classroom.

All in all, the decision represents a limited if significant erosion of church-state separation, and indicates that several conservative justices are champing at the big to go further. The impact of Espinoza is also likely to be limited if significant, as Matt Barnum explains:

It’s unclear whether the decision will have far-reaching implications in the short term, as the decision explicitly says that states without voucher programs will not have to open the funding floodgates to private schools.

But small voucher programs in Maine and Vermont that do bar religious schools are likely to have to change their rules. Laws that prohibit churches from operating secular charter schools might also be under threat.

Politically, this decision may mitigate some of the unhappiness being expressed by religious conservatives toward Roberts and the Court’s conservatives generally over their handling of LGBTQ rights and abortion laws. Espinoza does not constitute a full-blown judicial counter-revolution, but does hint at where a future Court might go if Donald Trump is reelected and SCOTUS’s right wing is strengthened.