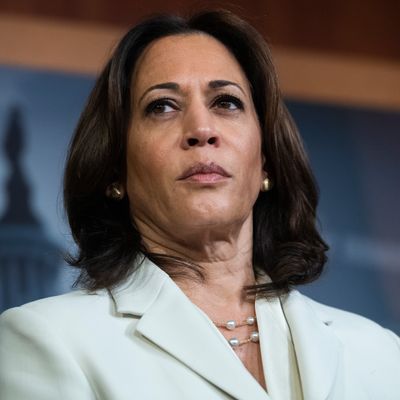

Kamala Harris’ name has never been far from the top of the informal rankings that influential Democrats, plugged-in elected officials, and powerful donors have quietly been keeping of Joe Biden’s likely running-mate prospects. But over the last few weeks, as she’s become a leading voice on police reform, the California senator’s position as a favorite has solidified.

Harris has been working with other Democrats on reform legislation that they hope can meet the moment. And just as calls for Biden to choose a Black vice-presidential candidate have multiplied in the wake of the murder of George Floyd and the subsequent protests, his campaign has entered an advanced phase of its selection process. In addition to Harris, the short list appears to include two officials whose prominence has increased in the eyes of many close to Biden as they, too, have responded to the national outcry: Congresswoman Val Demings, a former Orlando police chief calling for reform, and Atlanta mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms. But it’s Harris’ fellow senator Elizabeth Warren who many consider to be closest behind her, thanks in part to her credibility as a messenger on economic issues and her increasingly close relationship with Biden. Meanwhile, Amy Klobuchar — once a favorite — saw her standing tumble amid concerns about her history as district attorney in Minneapolis’ Hennepin County, and she removed herself from consideration this week, telling Biden she thought he should choose a woman of color. Other contenders are still thought to be under consideration, like former Obama administration national security advisor Susan Rice, Michigan governor Gretchen Whitmer, New Mexico governor Michelle Lujan Grisham, Illinois senator Tammy Duckworth, and Wisconsin senator Tammy Baldwin.

Biden has long said he’s looking for someone whom he considers ideologically “simpatico” and ready to assume the presidency, but as the political landscape has dramatically shifted, his process has, in some ways, simplified. He’s been leaning further than ever into direct contrasts with Trump, and some influential Democrats close to his team have been urging him to pick someone he trusts to attack Trump directly. Biden has been careful not to send public signals, but people close to him think he came close when he alluded to “this partnership going forward” on a fundraising call with Harris in April. She has recently been rallying her political network to support him, including financially: A fundraiser she hosted for him in early June brought in $3.5 million.

Still, just a few days later, Warren raised $6 million for him, and some in Biden’s campaign operation remain concerned about how Harris’s presidential campaign fell apart publicly and painfully last year. (She’s since trimmed her staff, and Biden recently hired one of her top advisers.) Others, too, often bring up progressive objections to her record as California’s attorney general and San Francisco’s district attorney. But she has been working to assuage those concerns by engaging with activists behind the scenes, to the point where some have changed their tune entirely. “She’s the front-runner,” a New York Democrat close to Biden’s campaign said to me recently. “There’s a lot of people that don’t want her to be it. But what’s the reason not to choose her?” Harris, for her part, doesn’t engage when asked about the VP role, usually demurring to say she just wants Biden to win.

As the spotlight has narrowed, Harris has been elevating her work with a small group of lawmakers like Cory Booker to offer a wide range of law-enforcement reforms. Their Justice in Policing Act proposes a ban on police choke holds, limits on the transfer of military weapons to departments, the establishment of a national registry of police misconduct, and restrictions on qualified immunity for law enforcement. “The status quo’s not working,” Harris tells New York. “Every time we talk about consequence and accountability it seems to be directed at the person who’s been arrested, and not the system.”

Let’s start with the police-reform legislation you’ve been working on. Are there any cities or departments that you currently see as a model for reform?

Hmm. There are some really good ones. I don’t have any current data on them, though. But over the years, different departments have done different things. Like Pastor [Michael] McBride, who I just did an event with, was helpful with the Oakland Police Department in doing some deescalation. I believe OPD was one of the first to ban chasing a suspect into a backyard. There are others that have done some really good work that was a basis for a lot of our recommendations around deescalation, including requiring waiting until a supervisor comes to the scene. Because waiting “X” number of minutes will have an exponential impact on whether that ends up being a lethal situation or not. There’s a lot of good data that has been compiled over the years that has been implemented by different departments on a variety of these issues. We had a notorious case in Sacramento involving a chase into a backyard. This has long been a practice of police officers, and it needs to stop, because it never ends well.

In Minneapolis, the city council’s members promised to disband and replace their police department. What was your reaction to that announcement?

Well, I think we have to reimagine how we are achieving public safety. We have to understand that if the goal is safety, one of the most effective ways to achieve that goal is to have healthy communities. Healthy communities are safe communities. So how do you achieve healthy communities? That should be the question. Well, you have access to health care and mental-health care. You have access to capital for small businesses. You invest in the public education system. You invest in affordable housing and increase home ownership, job skills development and jobs. When you see those things, you will see healthy communities. It’s status quo thinking, and it’s misinformed, to think that putting more cops on the street creates more safety. What creates more safety is when you invest in the health and well-being of a community.

Go to upper-class suburbs and what you’ll see is very little police presence, if any. But you will see well-funded schools. You will see higher rates of home ownership. You will see families that can afford to get through to the end of the month without worrying about putting food on the table. You will see thriving small businesses. So we need to have the budget reflect those priorities. I would talk about this during the campaign — it was my first policy rollout: teacher pay. Part of what I talked about throughout the whole year of campaigning was that two-thirds of public school teachers take from their own back pocket to help pay for school supplies, which is a statement about, one, what we’re paying teachers, but also that we’re underfunding public schools.

Look at it in terms of the fact that in many cities, one-third of the municipal budget goes to policing. With all of the responsibilities that a municipality has — that a city has — that one-third of that pie would be policing has to force us to really have an honest conversation about whether this makes sense, and whether that’s smart, in terms of the goal, the collective goal.

So in Minneapolis disbanding the police department and rebuilding something new appears to be the first step on a path like that. Do you see that as an applicable model for other cities?

To be honest with you, I haven’t seen enough of what they’re doing to really comment on what they’re doing. I’m not really clear yet on what they’re doing. Are you?

They haven’t laid out all the specifics of what will replace the current department —

I don’t really know what their plan is, so I don’t know how to assess it. But I will say this: We need police. I am not in favor of getting rid of the police. I personally prosecuted, for a long time, and specialized in, child sexual-assault cases. I want to know that those cases are going to be investigated, and that the people who commit those crimes are going to be arrested. I personally prosecuted homicide cases, rape cases. But that doesn’t mean that we don’t need to reimagine how we achieve public safety.

This gets to the ongoing debate about the “defund the police” movement, and its phrasing and goals.

I think I know what we need. I’m not going to get caught up in defining my perspective based on a hashtag. We need to reimagine how we achieve public safety, we need to critically examine whether our distribution of resources reflects our priorities, based on what we know is the smart way to achieve public safety and healthy communities. When we have spent decades defunding public schools and public education in this country, I know we need to critically assess this. When we have wholesale neglected the significance of treating mental health. The way I would talk about it in the campaign, I’d say, “In health care we think the body starts from the neck down. Well, what about the neck up?” We need mental-health services, which we’ve not been funding. So we have to do a better job of investing in communities in a way that it’s about their economic strength, it’s about their strength in terms of their educational opportunities, housing and affordable housing opportunities.

What role do you see for police unions moving forward?

We need them to be onboard with the idea that the status quo’s not working, and also that a bad cop is bad for good cops. We need to have a system that requires accountability for police officers that break the rules and break the law. Because here’s part of the problem — and I say this as a former prosecutor: Every time we talk about consequence and accountability, it seems to be directed at the person who’s been arrested, and not at the system. Are we holding the system accountable, and are we creating consequences when it’s not? That’s where we have to be, which is to say, the system also has to be held accountable, there have to be consequences when the rules are broken, when the laws are broken. That’s really the focus of our bill, the Justice in Policing Act. It’s very narrowly tailored to address the accountability and consequence piece on the issue of policing.

This weekend Senator Tim Scott said that limiting qualified immunity is off the table for Republicans. Did that surprise you? And how can you move forward if that’s true?

Well, I think that’s not a good place to start when you’ve not even had a discussion yet — to say something’s off the table. But this is something that we need to address. We need to address this issue of qualified immunity. Because, again, it’s been a barrier to accountability. People are marching in the streets because they rightly believe there are two systems of justice in America.

Passing this legislation, at least in the short run, would obviously require a lot of work with your Republican colleagues. There’s what Senator Scott said about his colleagues and qualified immunity, but then you also had Senator Rand Paul recently standing against your anti-lynching legislation. What’s your view of the Republican Party’s broader position on working together here?

You know, you’ve also got Senator Mitt Romney who’s out there speaking the words “Black Lives Matter.” So there’s clearly some diversity within the party, or within the elected representatives. I do hope that they will rise to meet this moment. I do hope that they see what I see in the streets, which is people who seemingly have nothing in common are marching together in step, knowing they have everything in common on this issue. Which is truly and fundamentally an issue about whether we’re going to get close to that ideal: equal justice under the law.

And then, at the same time, you have President Trump scheduling a rally in Tulsa for Juneteenth —

Well, he’s just being his typical self. No surprise there.

Speaking of the protests, I want to ask about spinning that energy forward. There’s been a decent amount of coverage about how some activists have expressed significant skepticism about the power of voting — arguing, basically, that it hasn’t gotten them much in the past. In some cases, it’s also skepticism about Vice-President Biden, in particular because of his work on the crime bill in 1994. How do you respond when you hear these concerns?

I understand it. I understand it. That it is not enough to say to people, “If you vote, your demands will be met,” when people have been voting, and their demands haven’t been entirely met, or, in many cases, haven’t even come close. I understand that, or I recognize it to be a valid perspective. But I would also caution that if you don’t vote, you can be sure your voice won’t be heard or reflected.

Let’s just back up for a second. In this election in November, if that’s what we’re talking about, instead of just having an existential conversation about voting, there is a clear choice. There’s the guy who says that there are equal people on each side, the guy who started the birther movement, the guy who has been full-time selling hate and division in our country, who has been using racist language to stoke fears and to appeal to a dark history that should be in the past, but he is resuscitating it as much as he can. There’s a choice between that and the guy who’s saying “Black Lives Matter”; who is saying, “I’m committed to reform”; who’s saying, “Racism is real, and I recognize it.” That is a reality. On the one hand you have someone who pulled out federal law enforcement to teargas peaceful protesters for a photo op. There is such a stark contrast. So we have the ability to at least end that pain. It’s not going to be enough in terms of where we need to go, but it will be a huge step forward.

Is there anything you would counsel Vice-President Biden to do now, though, to speak to this concern?

I think he’s doing it. He’s meeting with folks. He’s listening to folks. He’s rolling out policies and policy priorities. I think he’s speaking to the pain, he’s meeting with families. I think he’s doing it.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.