In the Trump era, the U.S. electorate has become less divided by race.

That might read like a typo. Throughout the 2016 campaign, pundits (including myself) posited that Donald Trump’s nomination would deepen the Republican Party’s woes with Black and Hispanic voters while potentially gaining the party some aggrieved white voters who had been deaf to its past nominees’ racial dog whistles — but could hear the billionaire’s foghorn loud and clear. Summarizing the conventional wisdom of four years ago, Peter Beinart wrote in The Atlantic that “by stigmatizing undocumented immigrants, Republicans have catalyzed the Latino cohesion that could be their undoing.” The election returns told a different story.

In 2016 exit polls, Trump boasted slightly higher support among Black and Hispanic voters than Mitt Romney had four years prior. Exit polls are infamously unreliable, and the difference between the Romney and Trump vote shares was tiny. So, the confounding 2016 results were plausibly disputed and then widely ignored. This year, however, the absence of “Latino cohesion” has become unmistakable.

In mid-September, the voting public as a whole was leaning about five points more Democratic than it had been in 2016 — and yet Hispanic voters were leaning nine points more Republican than they had been four years earlier. In a cycle with a more popular Democratic nominee — and a Republican incumbent presiding over an economic and public-health catastrophe that disproportionately harmed Hispanic communities — Trump nevertheless appears to enjoy more support within that community than he did before taking power. His standing among African American voters, meanwhile, appears to be the same or better than it was in 2016 in most national surveys, which is to say Joe Biden’s large improvement on Hillary Clinton’s performance in general-election polls is driven primarily by Democratic gains among whites. And this means that race is a less reliable predictor of voting preference in the Trump era than it was in the Obama one.

Of course, this does not mean that America isn’t riven by identity-based divisions. Our polity might not be as polarized by racial demographics as it was pre-Trump, but it is more polarized by attitudes toward racial inequality and immigration. And although 2016’s conventional wisdom about how Trump’s bigotry would reshape each party’s racial composition has proven false, the common sense about how Trump’s misogyny would reshape each party’s gender composition has been vindicated. In fact, to a large extent, the latter development explains the former.

Trump is for the boys.

Barring a giant polling error, the 2020 election will witness the largest gender gap in partisan preference since women gained the franchise. As CNN’s Harry Enten observed earlier this month, Biden’s average lead among women in recent interview polls is about 25 points; no nominee of either party has ever led by that much among women in a final preelection survey, not even in the landslide years of 1964 and 1984. And yet, in those same surveys, Trump leads among men by three points. In 2016, the gender gap in voting preference was 20 points; if current polls hold steady, it will be 28.

The historic salience of gender in our politics partially explains Trump’s surprisingly resilient standing with nonwhite voters. In a Fox News poll released earlier this month, Trump’s support among nonwhite men was two and a half times higher than his support among nonwhite women (25 and 10 percent, respectively). Last week, Jennifer Medina of the New York Times reported on the centrality of machismo to Trump’s appeal among Mexican American men:

[W]hat has alienated so many older, female and suburban voters is a key part of Mr. Trump’s appeal to these men, interviews with dozens of Mexican-American men supporting Mr. Trump shows: To them, the macho allure of Mr. Trump is undeniable. He is forceful, wealthy and, most important, unapologetic. In a world where at any moment someone might be attacked for saying the wrong thing, he says the wrong thing all the time and does not bother with self-flagellation.

… They said they saw his defiance of widely accepted medical guidance in the face of his own illness not as a sign of poor leadership, but one of a man who does his own research to reach his own conclusion. They see his disdain for masks as an example of his toughness, his incessant interruptions during the debate with Mr. Biden as an effective use of his power.

“We saw him being a boss,” said Edwin Gonzales, 31, who held a large American flag outside the Trump campaign office. “And for him to go down the escalator is basically the same thing — it’s like, ‘Dang, the boss has stepped down and he’s putting himself out there to be the president.’ That’s what’s exciting.”

As these quotes indicate, the fact that Trump’s performance of masculinity resembles a misandrist caricature — with its compulsive braggadocio, bawdy innuendos, and shameless, nigh-simian dominance displays — is a prime cause of 2020’s unprecedented gender polarization.

And yet, it would be a mistake to attribute this year’s gender gap entirely to Trump’s personal attributes. After all, women have been trending left, as men trend right, for decades now. And this development is not unique to the United States — rather, it is present across nearly all advanced democracies. Viewed in this context, Trump looks as much like a product of the gender gap as he does like a cause: It’s quite plausible that Trump would not have won the 2016 GOP nomination if the Republican coalition hadn’t already grown heavily male (in multiple state primaries, Trump performed significantly better among men than women).

America’s ongoing racial diversification has loomed large in popular accounts of our democracy’s future. And for good reason. But our justified fixation on the perils and promise of an increasingly multiethnic America has led some political analysts to give the ongoing transformation of gender roles short shrift. The emergence of a gender gap in voting preferences throughout the postindustrial world suggests that the forces pulling men and women into opposite political camps long predated Trump’s political career — and will be shaping our politics long after he’s gone.

Women used to lean right.

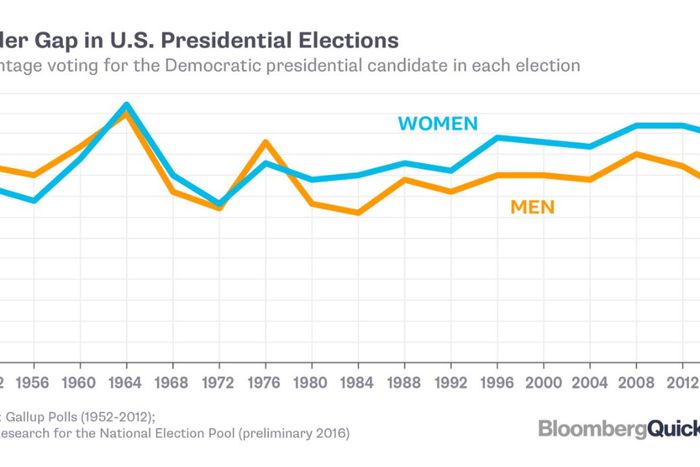

In the U.S., women have been voting to the left of men for four decades now. As a result, many contemporary political observers consider the female population’s relative liberalism to be a law of the political universe: Of course, women would, in the aggregate, favor the party of reproductive autonomy and social welfare, given their inherent interest in the former and their relatively greater propensity for empathy and cooperation.

And yet, a half-century ago, the common sense about women’s political leanings was quite different. Summarizing the conventional wisdom about female voting preferences in 1963, the political scientists Gabriel Almond and Sidney Verba wrote, “Wherever the consequences of women’s suffrage have been studied, it would appear that women differ from men in their political behavior only in being somewhat more frequently apathetic, parochial, [and] conservative.”

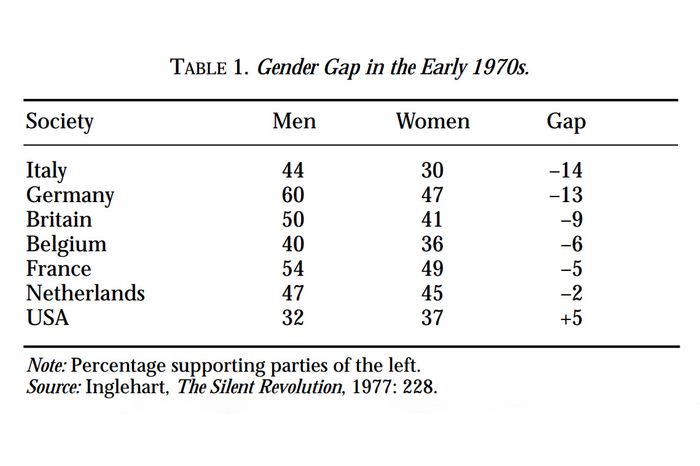

Indeed, throughout the 1950s, women were more likely to vote for Republicans than men were in the United States, while in Western Europe, men were still voting to the left of women in the early 1970s.

The dominant explanations for women’s conservatism in this period concerned their greater likelihood of attending church and abstaining from the labor force, according to the comparative political scientists Ronald Inglehart and Pippa Norris. At a time when trade unions anchored parties of the left, the underrepresentation of women in organized workplaces made them less likely to vote with labor. In many European countries, meanwhile, women’s greater religiosity made them more likely than men to occupy the pews of a church aligned with the center-right Christian Democrats.

In some contemporary polls, women across nations also expressed more conservative ideological views than men (although it is unclear whether this should be seen as a cause or effect of their partisanship). One possible explanation for why women might have leaned conservative in this period — but not in our own — is that the median female voter’s ideology evolved with her economic position: When a larger percentage of women in Western Europe and the U.S. depended on husbands for financial security, they arguably had a material interest in some aspects of social conservatism, such as its emphasis on familial obligation and the stigmatization of (male) infidelity. As remunerative employment became more available to all genders, however, more women came to understand such conservatism less as a safeguard against deprivation than an affront to their autonomy.

Regardless, over the ensuing five decades, gender-based voting patterns gradually flipped. The shift came first to the United States. In 1980, as Ronald Reagan firmly aligned the Republican Party with the “pro-life” movement, American women voted sharply to the left of men for the first time — and have remained to their left ever since.

For a while, comparative political scientists struggled to theorize the exceptional liberalism of U.S. women. But by the end of the 1990s, the American pattern had spread through much of Western Europe, which first witnessed gender de-alignment — as women ceased to be more conservative than men — and then gender realignment, as the contemporary gender gap asserted itself. Today, the “women, left; men, right” pattern is nearly uniform across advanced democracies.

The modern gender gap is (arguably) one of postindustrial capitalism’s signature products.

In a paper published at the turn of this century, Inglehart and Norris put forth a “developmental theory” of the gender gap. Whereas other analysts of the phenomenon often attributed it to factors peculiar to a given nation — such as the heightened salience of issues that tended to polarize men and women during a specific campaign — Inglehart and Norris argued that there was an inherent relationship between the postindustrial stage of economic development and the appearance of the modern gender voting gap.

Their theory goes (roughly) like this: Almost all preindustrial societies strictly circumscribed women’s social role, assigning them responsibility for child-rearing and discouraging their full participation in market economies. These social expectations persisted in weakened form through the first waves of industrialization in the West. But as these societies grew wealthier — and as the imperatives of capital gained ever-more supremacy over those of tradition — women grew less dependent on, and tolerant of, patriarchal convention. Meanwhile, relative prosperity also served to increase the prevalence of “post-material” politics — which is to say, a politics that privileges questions of personal freedom, self-expression, and gender equality over those of physical and material security — as a new, historically economically comfortable generation sought to shimmy up Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

These developments produced mutually reinforcing economic and cultural changes, which together fostered the modern gender gap in political preferences. Women’s mass entrance into the labor force increased their participation in the union movement as well as their aggregate level of concern with the provision of social-welfare services that could render the dual burdens of breadwinning and caretaking more manageable. Women also tended to become less religious. All these developments served to pull women toward the parties of the left. And this change in women’s social role and power further heightened the prominence of “post-material” questions in politics, which tended to polarize male and female opinion more than “the class politics of economic and physical security” ever had. Through an elaborate analysis of World Values Survey data, Inglehart and Norris demonstrated that women’s leftward shift was not wholly reducible to structural factors such as changes in their aggregate religiosity, class position, age, or rate of labor-force participation. All these variables were relevant. But a nation’s level of “post-materialism” was more predictive of how its women voted than any of those structural factors by themselves.

One can pick many bones with this theoretical framework (the millennial generation has an awful lot of material concerns, which seem to be reflected in its voting patterns; the decline of class politics is arguably more attributable to the imposition of anti-labor economic policies than the achievement of mass affluence; it’s hard to see how “gender equality” is not a materialist issue). But it’s difficult to dispute the paper’s basic empirical finding: that postindustrial development tends to produce a gender gap in voting behavior, as generations of women socialized into traditional gender roles are displaced by generations who were not.

In the 1990s, women in developing countries voted to the right of men – no matter their age – just as they had in the U.S. 40 years earlier. But in the advanced industrialized world of the 1990s, generational differences in women’s politics were stark:

Put Trump’s glittering misogyny to one side. Forget the GOP’s theocratic streak. The data above, compiled 20 years ago, would be sufficient to explain a large gender gap in 2020, through generational churn alone.

We’re likely to “mind the gap” for decades to come.

Neither the societal shift away from traditional gender roles nor the downstream cultural consequences of that shift are anywhere near complete. As Rebecca Traister has incisively argued, the growing prevalence of singledom among America’s rising generation of women is one of the most potent forces in contemporary politics. In 2009, for the first time in history, there were more unmarried women in the United States than married ones. And today, young women in the U.S. aren’t just unprecedentedly single; they also appear to be unprecedentedly uninterested in heterosexuality: According to private polling shared with Intelligencer by Democratic data scientist David Shor, roughly 30 percent of American women under 25 identify as LGBT; for women over 60, that figure is less than 5 percent.

It’s possible that this is more of a life-cycle effect than a generational change. But then one could have said that about a chart showing higher support for left-wing parties among young women 20 years ago. The (gradual) liberation of women from patriarchal gender roles is among the most profound changes in social organization that humanity has witnessed since the advent of representative democracy. It would be odd if a change this epochal — and ongoing — had the same cultural and political consequences for the third generation of women raised in its wake as it did for the first.

The future is a different country. There, the Trump presidency is ancient history and the confident predictions of today’s pundits brim with dramatic irony. But surveys of Zoomers bring us tidings from Tomorrowland. And they appear to describe a place where politics is (at least) as fraught with gender conflict as our own.