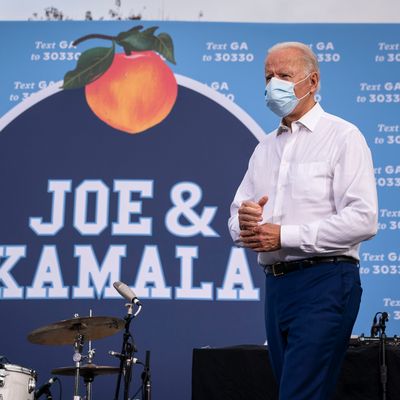

Favorable polling seems to have prompted Joe Biden’s last-minute campaign stop in Georgia on Tuesday, his first visit since he became the Democratic nominee and a final effort to nudge the state’s 16 electoral votes into his column by November 3. Trump won here by five points in 2016; Biden leads by a hair, 0.3 points, in the most recent poll by the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. If the vice-president wins, it will be the first time a Democrat has carried the state since 1992, and provide evidence that regional segregation patterns — which I wrote about at greater length in the current print issue of New York — didn’t pan out the way Trump hoped they would.

Biden made two stops, one of them mainly symbolic. Warm Springs, a town of about 400 residents just over 30 miles from the Alabama border, is unlikely to be a wellspring of determinative votes, but is where the country’s most vaunted Democratic president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, owned a private retreat and died in 1945. “This place, Warm Springs, is a reminder that, though broken, each of us can be healed,” Biden said, according to AJC, a reference to the region’s therapeutic waters. “That as a people and a country, we can overcome this devastating virus. That we can heal a suffering world. And yes, we can restore our soul and save our country.”

Biden’s other stop, Atlanta, was more practical. The capital city’s metropolitan area is ground zero for Democrats’ shifting fortunes in the state, as evidenced by their performance in recent elections. In 2018, Stacey Abrams, a Black former state lawmaker and voting-rights advocate, pushed then-secretary of State Brian Kemp, a Republican, to the state’s closest gubernatorial race since 1966. That same year, a Democrat won Newt Gingrich’s old congressional seat — Georgia’s 6th district — for the first time in more than four decades. Democratic Senate candidate Jon Ossoff is polling ahead of incumbent Republican David Perdue by a slightly larger margin than Biden is Trump. “There aren’t a lot of pundits who would have guessed four years ago that the Democratic candidate for president in 2020 would be campaigning in Georgia on the final week of the election,” Biden said. “Or that we would have such competitive Senate races here in Georgia. But we do.”

All three developments speak, in part, to dramatic population shifts. The Atlanta metro area added 730,000 new residents between 2010 and 2019, making it the fourth fastest growing metro area in the nation. Included in this influx was a New Great Migration — a decades-long reversal of the exodus that took 6 million Black southerners to new homes in the north and Midwest between 1916 and 1970. Many are returning: The region’s Black population grew by 17 percent from 2010 to 2019 — faster than whites or Hispanics (but not Asians, whose ranks swelled by 31 percent) — and most of its Black residents live not in Atlanta proper, but in its suburbs, which have experienced the majority of the region’s population and economic boom since the 1960s.

This has complicated Trump’s reelection pitch — if not necessarily forestalled it. As his national polling numbers have faltered, the president has pivoted to an outwardly segregationist bid, premised on stoking fear that a Biden win will bring more Black and brown people from big cities into white suburbs. His demagoguery has focused on an explicitly integrationist fair-housing rule implemented under President Obama — Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing, or AFFH. “Sleepy Joe Biden has pledged to ABOLISH Suburban Communites [sic] as they currently exist by reinstating Obama’s radical AFFH Regulation,” Trump tweeted on September 8. This strategy is especially relevant to Atlanta. Trump sees fallow ground here because, historically speaking, it has been. The piecemeal desegregation efforts that marked the civil-rights era and made Atlanta praiseworthy to outside observers was rooted in the idea that too much racial strife would be bad for business and cause everyone to suffer, as Kevin M. Kruse details in his mid-20th-century history of the region, White Flight. But while the city looked fairly harmonious compared to others like Little Rock and Birmingham, it housed a degree of conflict that was untenable. As greater numbers of Black residents moved into white neighborhoods, whites fled the city in droves, many of them joining white migrants from elsewhere in the surrounding suburbs, which exploded economically. Atlanta lost roughly 45,000 white residents between 1960 and 1970, and more than 175,000 more between 1970 and 1990. The political implications have been stark. The city hasn’t elected a white mayor since 1973. Many of the metro area’s suburban counties became reliable conservative strongholds in subsequent years, personified by dog-whistling officials like Gingrich, who contrasted the freeloading ethic of Black Atlanta with the supposedly harder workers of its white suburban counties, according to Kruse.

Trump’s appeals have these suburbs clearly in mind. But many of them don’t exist anymore, replaced instead by Black-majority municipalities. This hasn’t precluded an enduring audience for Trump’s messaging, though, and polling provides further evidence. According to a New York Times/Siena poll from late September, Atlanta’s inner suburbs appear to be in the bag for Biden, but Trump leads by a similar margin in its outer suburbs, 57 to 33.

Georgia is still a purple state only in theory. Trump is the favorite there until proven otherwise, and Atlanta’s suburbs are changing more quickly than the state as a whole, which is still more than half white, and whose white residents are overwhelmingly conservative. A visit on Tuesday seems less likely to tilt the election decisively in the vice-president’s favor than fall into the “can’t hurt” category — especially if it boosts Ossoff and other Democratic contenders. Nor should too much be read into a possible Trump loss. The president’s choice to demagogue integration won’t change the material reality of segregation in Atlanta either way. Biden winning would simply mean it wasn’t enough to deliver him reelection. It would put national conservatives on the defensive in Georgia using an issue they’ve feasted on for decades.