The economic power of multinational corporations has become a threat to the political freedom of American citizens. There is no hard border between private and public authority; how CEOs choose to govern their firms influences how voters choose to govern themselves. When Americans lack the material power to assert their liberties, the Bill of Rights becomes a bill of goods; there can be no true “right to free speech” when every megaphone is owned by unaccountable elites. Therefore, to strengthen our democracy, the federal government must curb the prerogatives of private property.

Or so conservatives have taken to arguing lately.

Disaffection with capitalism has been growing on the right for years now. But Twitter’s decision to ban the insurrectionist-in-chief — and subsequent moves by Google, Amazon, and Apple to effectively shutdown Parler, a far-right-friendly Twitter competitor — has swelled the ranks of “conservatives against free enterprise.” Now, it is only the right’s self-styled populists who are decrying the tyranny of woke capital. Even self-described libertarian Ben Shapiro suggested Sunday that Big Tech needs to be regulated since “the technological instruments necessary for speech are located in essentially three companies, all of which are moving toward like-minded censorship.” Other Republican lawmakers and commentators have argued that — unless the U.S. government stops private companies from running their businesses as they see fit — America will become indistinguishable from communist China.

The right’s anti-Twitter tantrum is hysterical, hypocritical, and partly cynical: As one Republican strategist told Politico, decrying Big Tech’s censorship helps to shift “the narrative of the moment” away from Trumpist terrorists’ ongoing efforts to disrupt the peaceful transfer of power and toward “a larger, more existential threat for the future of the country.” Meanwhile, it is hard to square Shapiro’s claim that three companies own “the technological instruments necessary for speech” with his dogmatic denunciations of positive liberty in other contexts; apparently, the podcast host believes that citizens are silenced when private tech firms deny them micro-blog accounts for being fascists — but not when private hospitals deny them life-saving medical treatments for being poor. And, of course, had a sitting Democratic president just sicced a terroristic mob on Congress to block the certification of a Republican’s election victory, there’s no doubt that conservatives would deem the suppression of an insurgency more pressing than the restoration of antifa-aligned Twitter accounts.

The right’s fears of creeping corporate liberalism aren’t baseless.

All this said, the right’s concerns about the power of major tech platforms have some merit. Twitter’s ban of Donald Trump was more than defensible, but its capricious de-platforming of countless other accounts is troubling. Given the website’s influence on elite discourse, the fact that unaccountable corporate managers can bar individuals from participating in debates on it — without explanation or opportunity for appeal — stands in tension with democratic ideals. Amazon’s decision to revoke its web services from Parler is a beneficent development in the near term, but may prove a hazardous precedent in the long run. A single social-media site dictating user standards is one thing; the private companies that own the infrastructure of the internet requiring all social-media sites to adopt those opaque standards is another. In the present context, Parler’s facilitation of far-right organizing is likely a greater threat to democracy than Big Tech’s control over the websites it hosts. But empowering Jeff Bezos & Co. to set the boundaries of acceptable political opinion is less than ideal for small-d democrats — and genuinely threatening to Trumpian conservatives.

The right’s claims of persecution are often hallucinatory and almost always exaggerated. And their complaints about Big Tech aren’t much of an exception. Even as Ben Shapiro cries that conservatives have lost “the technological instruments necessary for speech,” the right still lays claim to America’s most-watched cable-news network, highest-rated political talk-radio shows, and most-read Facebook articles. The algorithmic programming of Facebook and Twitter — which directs readers away from dry reporting on local corruption and toward lurid conspiracy theories — has been a boon to the right in this country and many others.

Yet, it is also the case that every major tech company relies on a workforce that is hostile to conservatism. In 2021, American politics is polarized along lines of education, regional density, religiosity, and comfort with diversity — and Silicon Valley is powered (largely) by college-educated, city-dwelling, secular, cosmopolitan laborers. Which is to say: The elite professionals whom tech firms compete to recruit and retain are almost uniformly left of center — especially, on the cultural issues that animate the GOP’s mass base. And this reality does give liberal cosmopolitans some influence over how social-media platforms curate public discourse. As a liberal cosmopolitan, I think this is mostly to the good: A world where tech companies face hard limits on how much they can monetize fascist organizing — or censor progressive advocacy — before undermining their own labor needs is preferable to many alternatives. But the overrepresentation of liberals among the professional elite does threaten the right’s media influence — and, perhaps more importantly, its ideological coherence.

Why conservatives are losing their investment in the “free-enterprise system.”

The modern conservative movement was born to protect the prerogatives of private power from the whims of the public sector. This foundational commitment was the glue that bound together anti–New Deal industrialists, anti-civil-rights segregationists, and anti-feminist Christians: The first wished to prevent federal labor laws from weakening the power of bosses in their factories; the second, to keep federal civil-rights legislation from eviscerating the power of whites to exclude Blacks from patronizing their businesses; and the last, to keep federal anti-discrimination statutes and welfare programs from undermining the dependence of women on their husbands. Thus, the protection of private realms from public intrusion was a principle that could unite disparate conservative constituencies.

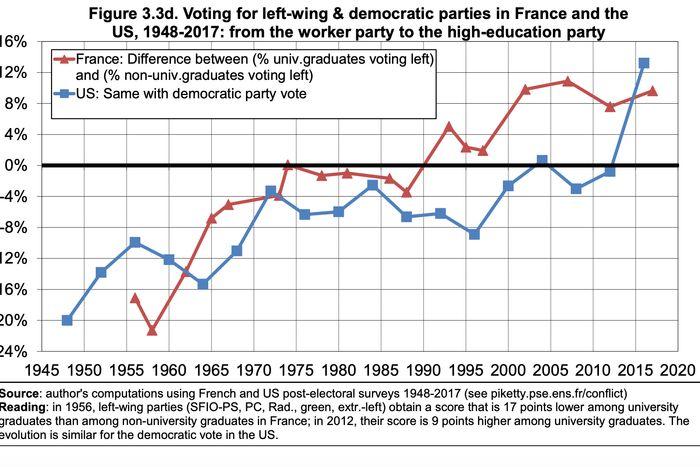

Yet this principle was forged in a specific sociopolitical context. In the New Deal era, the federal government was a bastion of liberal strength, while conservatives were wildly overrepresented among the nation’s corporate and professional elite. When Franklin Roosevelt returned to Harvard for his alma mater’s 300th anniversary in 1936, his visit provoked protests and boycotts from a well-born student body that reviled him as a class traitor. Not all college students of the mid-20th century were reactionaries, of course. But between the New Deal’s dawn and Richard Nixon’s election, college-educated Americans voted far to the right of those without diplomas; it wasn’t until 2004 that a Democratic presidential candidate performed better with the highly educated than with the public writ large (and even then, only barely). And while it is true that a large segment of big business aligned itself with the New Deal Democratic Party, by the time the conservative movement came to power, the bulk of corporate America had rallied behind Reagan’s Republicans.

As already indicated, today’s political economy looks quite different. U.S. college graduates are now far more Democratic than the public as a whole. And the urban-dwelling, professional elites who staff America’s tech and finance industries are even more liberal than the average university grad: According to Democratic pollster David Shor, less than 5 percent of Harvard’s student body voted for Donald Trump in 2016, while college Democrats outnumber college Republicans on the Stanford Law School campus by a ratio of (roughly) 20-to-one. For these reasons, among others, the most economically prosperous and productive regions of the U.S. are now also among its most Democratic: Joe Biden won only 509 of America’s 3,056 counties, but those 509 encompass 71 percent of all U.S. economic activity.

What’s more, Democrats aren’t just overrepresented among corporate America’s elite workers; they also predominate among its most-coveted patrons. Consumer-facing companies have long focused on courting the young, since they are 1) more likely to try new brands and products than the old and 2) less likely to die soon, making their brand loyalty more valuable. At a time of historic generational polarization, which has rendered supermajorities of millennials and Gen-Zers hostile to conservatism, America’s marquee brands have taken to performing their allegiance to the “woke” side of America’s culture wars.

The movement for “small government” may learn to stop worrying and love authoritarian state-capitalism.

By itself, cultural liberalism’s conquest of corporate America would be sufficient to weaken the right’s commitment to protecting private power from public intrusion. But this commitment is also being eroded by a second consequence of education polarization: Even as conservatives have lost influence at the commanding heights of the private economy, they’ve secured wildly disproportionate influence over public policy.

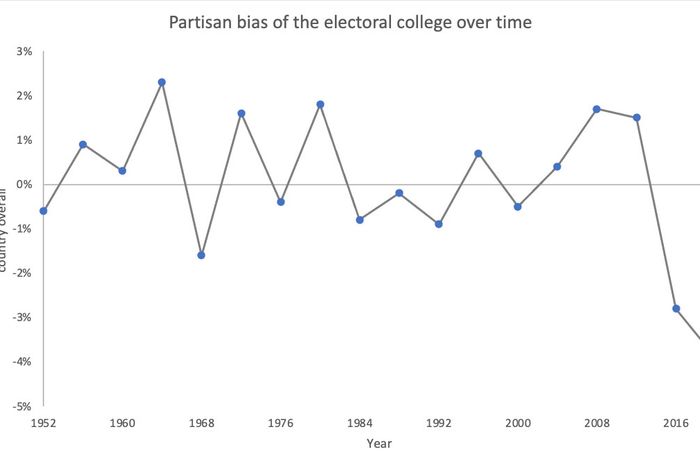

Under Donald Trump’s leadership, the GOP has swelled its margins among rural, non-college-educated voters — who are overrepresented in state legislatures, the House, the Senate, and the Electoral College. The median U.S. state is now roughly 6.6 percent more Republican than the nation as a whole, which gives the GOP a massive advantage in the battle for Senate control. Meanwhile, the “tipping point” state in the Electoral College was four points more Republican than America writ large in 2020; which is to say, had Joe Biden won the popular vote by “only” 3.9 percent last November, Donald Trump would have likely won reelection. Finally, conservatives now dominate the federal judiciary, atop which a 6-3 conservative majority reigns supreme.

For nearly a century, the conservative movement’s animating ambition has been to transfer power away from the federal state and toward the private sector. This aim remains consistent with the interests of the movement’s libertarian plutocrats, and to a lesser extent, its upper middle-class nativists and anti-Black whites: Conservatives may punch above their weight in American politics, and corporations may now evangelize for social liberalism, but no “woke” Wall Street bank will ever impose inclusionary zoning on an affluent white suburb that wishes to remain so, nor will any progressive tech startup ever systematically redistribute income from (predominately white, native-born) upper middle-class households to (diverse, disproportionately foreign-born) working-class ones – only the government can do that.

But for conservatives who are more invested in winning the culture war than protecting material privilege, the gospel of Reagan makes less sense today than it ever has – because in 2021, transferring power away from “big government” and toward Corporate America means shifting authority away from institutions that overrepresent social conservatives and toward ones that underrepresent them.

Some on the right resolve this contradiction through cognitive dissonance. Others, like Ben Shapiro, generate facile arguments for why regulating conspicuously anti-Trump corporate sectors is consistent with free-market conservatism, even as virtually all other forms of regulation are not. A few on the “populist” wing of the movement, however, are imploring their co-partisans to grapple with their betrayal by “woke capital.” As Rachel Bovard of the Conservative Partnership Institute recently wrote for American Greatness:

Amazon recently banned books contradicting the popular narrative about COVID-19 and a documentary from Shelby Steele, an African American writer, on the death of Michael Brown, before reversing themselves after popular outcry. The platform will not let many mainstream conservative organizations use its philanthropic arm, Amazon Smile, to raise money, but does happily turn over its services to Planned Parenthood.

Bank of America will no longer lend money to certain gun manufacturers. Citibank will not process some gun sales by their own customers. Wells Fargo, JP Morgan Chase, and U.S. Bank will no longer provide services to the private prison industry in protest of President Trump’s immigration policies. These same federally insured banks and a handful of others now refuse to provide depository services to federal contractors who do work for Immigrations and Customs Enforcement. Payment and funding sites like Paypal, GoFundMe, and Patreon recently banned users they deemed “alt-right,” even when those users did not self-identify as such.

…Republicans should remain faithful both to capitalism and the free market that has made this country an enviable powerhouse. But we should shed the theology of market worship that blinds us to concentrated and collusive power being used in ways that are antithetical to both a free society and to the individual liberty upon which that society is built.

Bovard never specifies how, precisely, this circle should be squared. How does one remain “faithful” to the “free market,” while preventing online retailers from refusing to sell Alex Berenson’s book, or banks from refusing to lend to gun manufacturers? Isn’t giving private firms and individuals discretion over investment and commerce the very definition of remaining faithful to capitalism?

To this point, the incendiary character of the populist right’s rhetoric is absent from their policy proposals. Josh Hawley’s proposed revisions to Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act — the law that immunizes social-media platforms against liability lawsuits based on the written speech of their users — may be worthwhile. Regardless, they are modest, incremental measures that would not address the cultural right’s core concern: Its declining hegemony in the halls of private power.

The disparity between the catastrophic tenor of Hawley’s description of creeping corporate Marxism — and the modesty of his prescriptions for combating it — reflects two challenges facing the enemies of “woke capital”: 1) forcefully contravening the interests of corporate America as whole would jeopardize the Republican Party’s remaining business support, while 2) proposing the selective deployment of state power against firms that antagonize conservative constituencies would mean explicitly embracing authoritarianism.

Thus, for now, the fact that the movement for “small government” enjoys more influence over the state than it does over the corporate sector is having little influence on its policy agenda. But if the right continues in the direction it has long been trending — away from corporate conservatism and toward white Christian revanchism — the contradiction between the movement’s outsize power over the state and its learned opposition to state power will only grow more conspicuous.

Conservatives can’t secure the cultural dominance they long for within the confines of 21st-century capitalist democracy. If they can find the will to replace that system with one more statist and authoritarian, however, their overrepresentation at every level of government may offer them a way.