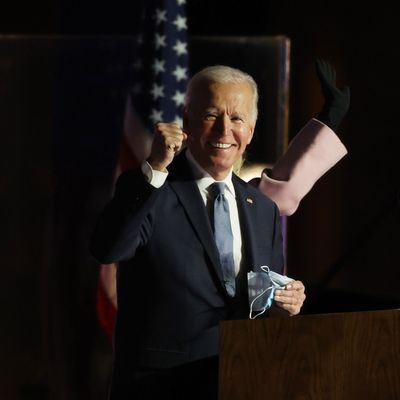

Joe Biden won’t take office for another five days, but he’s already told Congress to start warming up the money printer.

On Thursday night, the president-elect unveiled his $1.9 trillion COVID-19 rescue package. The proposal is historically large, refreshingly progressive, needlessly complicated, lamentably incomplete, and, unless Biden has blackmail material on 10 Republican senators, almost certainly dead on arrival in the Senate if the administration sticks to its current legislative strategy.

If you’re looking for a more detailed summary of the plan’s merits and flaws than that sentence provided, here’s a rundown of what’s good, bad, and odd about the next president’s first agenda item:

The good:

It suggests the Democratic Party is finally recovering from its debilitating deficit-phobia.

The last time a Democratic president came to power, America’s official unemployment rate stood at 8.1 percent. Average household wealth in the U.S. had just plunged. The global financial system had gone shaky at the knees. Meanwhile, America’s national debt was $9 trillion, or roughly 60 percent of GDP. And with Democrats in control of the presidency, a filibuster-proof majority in the Senate, and a large majority in the House, they opted to pass a grand total of $787 billion of stimulus. Within two years, even as unemployment sat near double digits, Barack Obama pivoted to deficit reduction.

Twelve years later, America’s unemployment rate sits at 6.7 percent. Thanks to the CARES Act’s relief checks, the Fed’s interest-rate cuts and support for markets, and this year’s COVID-induced contraction on consumption opportunities, most U.S. households are better off financially now than they were before the pandemic. The global financial system is stable, and stock values are near all-time highs. Meanwhile, America’s national debt is $27 trillion, which is more than 100 percent of GDP. Democrats have only a slim majority in the House and a razor-thin one in the Senate. And Joe Biden — a man who spent the 1990s arguing that America’s (then comparatively minuscule) debt load required cuts to Social Security — is calling on Congress to up its total stimulus spending on this crisis from $2.75 trillion to $4.65 trillion.

And within one month, Biden intends to come back to Congress to call for another multitrillion-dollar spending bill.

As a substantive matter, there’s a strong argument that Biden’s relief package remains too small. According to some estimates, the output gap for the U.S. economy in 2021 — the gap between how much economic value the nation could produce if its labor and capital were fully utilized and how much it is on track to produce given expected levels of demand — remained greater than $3 trillion as of December. And some of the proposals in Biden’s $1.9 trillion plan won’t make their impact felt until 2022.

All this said, Biden’s proposal is large by the austere standards of all past fiscal policy. Combined with what Congress has already enacted, it blows the New Deal’s deficit spending out of the water. One might dismiss the Democrats’ embrace of pump-priming as a one-off response to a world-historic crisis. But the abominably slow post-2008 recovery, and the persistent wrongness of deficit hawks’ warnings of imminent inflation, had already affected a sea change in technocratic opinion on public debt before COVID hit. The pandemic may have been necessary to transform intellectual consensus into the political variety. But unless Biden’s plans trigger dramatic price increases, there’s reason to believe they will mark a durable change in the Democrats’ fiscal orthodoxy.

Which would be good for America and for the party. As Rick Perlstein documents in his superb new book Reaganland, under Jimmy Carter’s leadership, the Democrats abandoned their identity as the party of full employment, and embraced the mantle of shared sacrifice. A little over a decade later, Bill Clinton’s surrender to the “bond vigilantes” — and the tech boom that coincidentally followed his deficit cuts — solidified the party’s commitment to fiscal “responsibility.” This faith in austerity allowed Republican presidents to play Santa Claus while Democrats paid tax collector. It also created the intellectual and political environment that led Barack Obama to egregiously underspend during the 2009 recession, a decision that had grievous economic consequences for the country, and likely, political ones for the Democratic Party.

Biden’s big bill suggests the Democrats have finally learned to stop worrying and love printing the world’s reserve currency to promote full employment and social welfare.

It includes landmark wage reforms.

While most of the provisions in Biden’s plan are geared toward temporary relief (more on that point in a minute), it also includes a permanent increase in the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour. What’s more, that minimum would apply to tipped workers, who currently rely on their customers’ generosity in order to secure a living wage.

If enacted, the impact of this policy would be massive. Progressives and moderates have spent the past few weeks squabbling over the size of onetime relief checks. But the $15 minimum wage would provide full-time workers at the current federal wage floor (or below) with a permanent, annual pay increase of roughly $16,000. According to the CBO’s 2019 estimate, such a policy would raise the wages of 17 million Americans.

It’s full of vitally necessary relief and public-health measures.

The proposal would:

• Provide most Americans with a $1,400 relief payment, bringing the total value of the second round of relief payments to $2,000. Notably, children and adult dependents are eligible for these payments too. So a single mother who cares for a child and a disabled sibling would receive a $4,200 check.

• Increase weekly federal unemployment benefits to $400 a week and extend them through September. (Freelance and gig workers who received federal benefits through the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program would be covered by this provision.) At present, that benefit is only $300 a week and set to expire in mid-March.

• Provide $20 billion to scale up the nation’s vaccination capacities, $50 billion for testing, $30 billion for the Disaster Relief Fund, and $10 billion for domestic pandemic-supplies manufacturing.

• Create 100,000 new jobs in public health to aid testing and vaccination efforts, and reduce unemployment.

• Invest $130 billion into helping schools reopen safely (through the implementation of social-distancing protocols, improvements in ventilation, and other steps).

• Expand paid-leave coverage to 106 million Americans.

• Increase federal rental assistance by $30 billion, provide $5 billion in emergency housing assistance to the homeless, and extend the eviction moratorium through September.

• Deliver $350 billion in fiscal aid to states and cities.

• Invest $40 billion in child care.

• Provide hard-hit small businesses with $15 billion in grants.

• Increase the child tax credit to $3,000 per child between the ages of 6 and 17, and $3,600 for those under 6.

• Increase the Earned Income Tax Credit from about $530 to $1,500, while expanding eligibility.

It’s just the beginning.

As mentioned above, Biden has made clear that this package is only step one. After “relief” is passed, he intends to introduce a larger “recovery” package consisting of investments in the nation’s climate and caregiving infrastructure.

The bad:

The plan erects a “pop-up welfare state” instead of a permanent one.

Many of the bill’s provisions make sense as temporary, emergency measures (we don’t necessarily want to spend tens of billions a year on small-business grants in non-pandemic conditions). But other policies fill holes in America’s threadbare safety net, only to let them reopen this October.

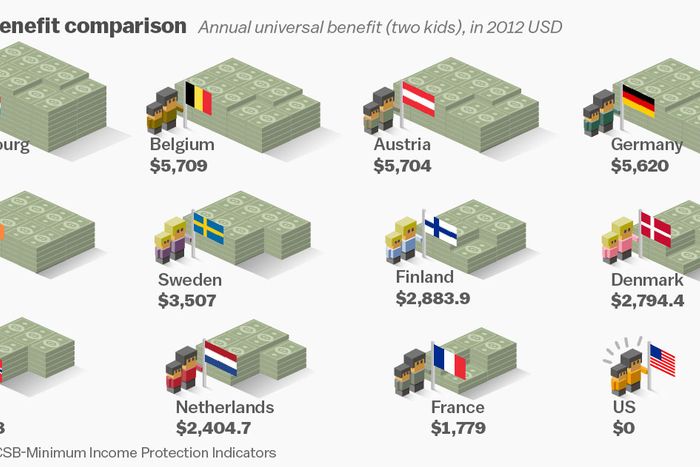

Canada, Australia, and just about every country in the European Union provides parents with a direct cash benefit to help defray the costs of raising children. The United States, meanwhile, merely has a child tax credit that leaves low-income families with only $1,400 in aid (and then, only if they know how to claim their credit). Increasing aid to children is good during a pandemic, but using our nation’s unparalleled wealth to prevent kids from living in poverty is a good thing no matter what public-health conditions are like. And the same can be said of the bill’s paid-leave provision, which also expires by Halloween.

It’s true that temporary social programs often become permanent; once Americans get a taste of that sweet, sweet social democracy, they usually don’t want to give it up. But there’s no reason to engineer a fiscal cliff here. By this time next week, Democrats will control both houses of Congress and the White House. They can and should make permanent social reforms now. If a single Democratic senator from a state with a GOP governor becomes incapacitated, Mitch McConnell will become Majority Leader again. Democrats must act while they have the chance.

In addition to being temporary, some welfare provisions are poorly designed.

Through its increases to the CTC and EITC, the Biden plan aims to provide income support to parents and working-class households. And these provisions would indeed be a significant improvement on the status quo. But dispensing aid through these kinds of tax credits, rather than through the provision of direct cash benefits, is both substantively and politically flawed.

On substance, means-tested tax credits require eligible households to identify themselves. This shifts a logistical burden from the government to citizens, and those most in need of help often fail to shoulder that burden. As People’s Policy Project co-founder Matt Bruenig notes:

According to the IRS, only 78 percent of eligible tax units receive the EITC benefits that they are entitled to. And, according to the Census, nonparticipation in the EITC is skewed towards lower-income families with children. Indeed, if you look at who actually gets the EITC based on IRS administrative data, rather than simply assuming everyone who is eligible gets it, you discover that conventional estimates of how much money the EITC provides to poor families are vastly overstated. For example, in 2014, the tax models tell us that the EITC lifted 4.8 million people over the federal poverty line while the actual IRS data tells us the real number was just 3.2 million people. This means that most estimates of the EITC’s impact—including the estimates used in the graphs above and the figures published frequently by the Census and other think tanks—overstate the EITC’s antipoverty impact by 50 percent.

As a political matter, meanwhile, traditional tax credits are much less visible to their beneficiaries than direct cash aid. The COVID relief checks were technically advance tax credits. But they were not administered through tiny reductions in tax withholding on paychecks. Rather, they appeared as a noticeably large payout, courtesy of Uncle Sam. There’s no reason Democrats couldn’t apply this model to other forms of social welfare. For example, they could do as Bruenig proposes, and have the Social Security Administration directly send monthly cash payments to every child in the country, or, failing that, all those below the existing income thresholds. Even if one kept the fiscal value of Biden’s child-aid proposal constant, dispensing aid through this mechanism would make benefits easier to access and harder to miss.

The Democratic Party’s attachment to providing aid through low-visibility tax credits may have made some sense in the political economy of the 1980s and 1990s: It was a fundamentally defensive strategy, aimed at reconciling the goal of social welfare with a reactionary political consensus that Democrats both responded to and perpetuated. But in 2021, government checks are popular. And many conservative wonks support aid to children specifically. Democrats should meet the moment, and ditch arcane tax credits for more visible and inclusive forms of social aid.

The expiration of temporary relief measures is triggered by an arbitrary date rather than objective economic conditions.

Finally, even if one posits that a $400 weekly federal unemployment benefit should be understood as a recession prevention (and/or mitigation) measure, rather than a permanent social benefit, it wouldn’t make sense to have the policy end on October 1. Rather, if we view enhanced UI as a tool for averting downturns by propping up consumer purchasing power in times of high unemployment, then the policy should only phase out once certain objective macroeconomic conditions are met — say, once the unemployment rate dips below 4 percent. Such triggers have been a longtime cause of progressive policy wonks and legislators like Senator Ron Wyden. Biden has expressed sympathy for the proposal, but for whatever reason, they aren’t included in his plan.

The odd:

Uncle Joe is turning the money printer up to 11 — if 10 Senate Republicans let him.

The deficiencies outlined above might reflect the oddest aspect of Biden’s plan: its legislative strategy.

Senate Democrats could vote to abolish the legislative filibuster, and then pass Biden’s plan on a party-line basis. But West Virginia senator Joe Manchin has vowed to keep the filibuster in place. In effect, this means that all regular legislation will need 60 votes to clear the Senate. The only exception to this rule are bills passed through the budget-reconciliation process, which enables legislation pertaining to the federal budget to pass the upper chamber with a simple majority.

Biden’s official position is that he would like to pass his relief bill through the regular legislative process, and save reconciliation for his giant “recovery” package. Which means that he apparently believes he can get 10 Republican senators to vote for this proposal. This desire to win bipartisan backing may explain why the plan structures expansions of social welfare as temporary relief measures: Republicans have shown that they are willing to abide certain forms of social spending in a pandemic, but not in other contexts.

But it’s hard to see how Biden could really believe there are 10 GOP votes for a $15 minimum wage, or $350 billion in fiscal aid to states, or, frankly, most of the items in his proposal. It’s possible then that this gesture toward bipartisanship is intended to fail: Perhaps, the idea is to make the GOP an offer it can’t accept — but which the voting public overwhelmingly supports — and then say, “Well, we tried for unity but those Republicans wouldn’t even support the $15 minimum wage that red state voters are clamoring for, so we’re just going to roll everything into one giant, partisan reconciliation bill.” Alternatively Biden may simply be making an opening offer full of provisions he’s ready to concede for the sake of a bipartisan compromise. Regardless, the proposal strikes a weird balance between maximalism and pragmatism. It withholds a permanent expansion in the child tax credit (an objective some congressional Republicans support), but includes a giant minimum-wage hike (an objective that virtually all congressional Republicans oppose).

Hopefully, Biden & Co. know what they’re doing. All in all, the president-elect’s economic plans look good on paper. But the only thing that matters is how they’ll look when (and if) they reach the president’s desk.