Up until about a year ago, carrying mail for the United States Postal Service was among the most predictable ways to earn a living. My father did it for 20 years, and I worked alongside him for two of them. You show up, throw magazines and loose letters into the labeled slots at your designated mail case, and deliver the route. You come back when the truck is empty, and the next morning, you get to work filling it up again. A Sisyphean means of community service. “Every day!” echoing in a sing-songy voice on the floor by carriers with a strong sense of gallows humor: The mail never stops, and it’ll keep going long after they’re gone.

Until last year, that is, when the pandemic began to crush this American institution under the weight of its sworn duty. As frontline workers, carriers began getting sick: By September last year, roughly 8 percent of postal workers had taken time off as a result of illness or exposure, a percentage that surely increased along with cases. Considering the increase in overall mail volume thanks to the pandemic’s e-commerce boom, this resulted in overworked carriers covering unprecedented levels of empty routes. On-time delivery of presorted first class mail fell from 94 percent at the end of 2019 to 91 percent after the start of the pandemic in 2020.

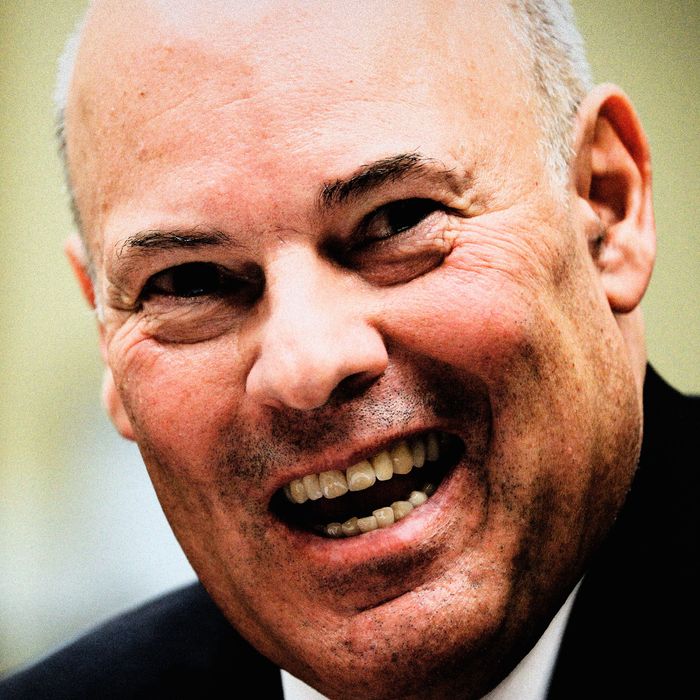

The pandemic would’ve been enough, but in May 2020, former logistics CEO and Trump donor Louis DeJoy was named Postmaster General. The hiring was criticized from the start as a conflict of interest on two different fronts: Not only was DeJoy seen as a Trump loyalist, but he also had millions invested in USPS competitors or contractors, the very companies that would most benefit should the post office become another federal institution stripped and sold for parts to the profiteers. As such, when he began ordering carriers to hit the street at specific times, often leaving mail behind in the process and disassembling mail-sorting machines, it wasn’t clear whether it could be best explained by sheer incompetence, an attempt to undermine an election, or a desire to kill the very service he was meant to advance. By October, DeJoy’s changes caused on-time delivery to fall all the way to 86 percent nationally, with rates below 80 percent in major cities like Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Detroit. To put a finer point on just how ineffective his leadership was, even these dismal numbers represented an improvement over previous months, all because injunctions required the USPS to roll back some of DeJoy’s policies ahead of the election.

Carriers who had longed joked about the mail never stopping started to wonder if they’d spoken too soon. “People are always scared that the post office is gonna die or whatever, or they’re gonna take away Saturday delivery. When the last postmaster left, it was right after DeJoy, and on his way out, he says to me: ‘Young man, get as much money as you can the next few years, because this is going away,’” said a carrier in southeastern Pennsylvania who has worked seven days a week since last March. “This time feels different.” A continued decline for the postal service also means a narrower pathway to the middle class for Black Americans, who are 27 percent of the USPS’s workforce.

Saving the post office became a rallying cry during the summer of 2020, as national media and politicians began to draw attention to the disruptions in service and the possible nefarious purpose of a Trump appointee sabotaging mail-in votes that skewed heavily Democratic. Joe Biden even made it a key part of his campaign: He laid out a comprehensive plan to save the post office in October and accused Donald Trump of deliberately undermining the election.

Once it became clear that DeJoy’s bungling hadn’t prevented Biden from winning the election, the issue mostly fell out of the news. Despite that, working conditions for postal workers and mail carriers have remained largely static for the same reasons they’d deteriorated in the first place. The pandemic rages on, and sorting machines are still decommissioned, causing massive backups in mail volume and sorting that clerks and carriers simply can’t keep up with. The issue created by eliminating sorting machines is one of extreme volatility within individual branches. Some days are impossibly light, others a flood. “My base average usually stays within a couple hundred pieces day to day, but I’m going from like 600 letters one day to 2,800 the next,” says a carrier on the Central Coast of California. While it’s difficult to pinpoint a precise reason, he says, “… it’s certainly was not the norm at any other point in my career.”

“Not the norm” feels like an excellent summary of the transition period between the previous presidential administration and this one. A few postal workers expressed some degree of understanding for the reduced urgency around the problems. “You’ve got the pandemic, you know. You’ve got the vaccine. There’s a lot that kinda pushes it to the back burner,” says Larry King, former president and current treasurer of the National Association of Letter Carriers’s Local 520 in Uniontown, Pennsylvania.

Despite their understanding, however, the urgency among letter carriers remains just as high as it had been before the election. DeJoy continues to stall on the presentation of his ten-year reform plan for the USPS, telling the House Oversight Committee last week that they would likely have it “some time in March,” without committing to a date. When asked to elaborate on what would be included in the plan, DeJoy used the indecipherable jargon trail blazed by other CEOs faced with questions they have no answers for — “unachievable hurdles” and “aligning to the new economy” and “better operational management” and other preemptive justifications for what will inevitably be internal cost cuts, reduced service quality, and increased postage rates. There is no evidence that DeJoy’s mission, which has appeared to be to destroy the USPS entirely, has veered from its course. If Biden plans to save the post office, as he pledged to do on the campaign trail, then there’s little time to waste in taking action.

To his credit, Biden acted immediately after DeJoy delivered his testimony to the House Oversight Committee, naming three nominees to fill all but one of the four open vacancies on the postal board of governors. Assuming confirmation from the Senate, that would create a perfectly balanced board, with four Democrats, four Republicans, and one independent (Amber McReynolds, chief executive of the Vote at Home Institute, a voting-rights group with support from liberal and left-leaning organizations). On the surface, it would appear that Biden has a clear majority with four Democrats and one independent sympathetic to his side. A majority is necessary to remove DeJoy, as the president doesn’t have the authority to fire a postmaster general, only a vote by the board members can do that. But one of the Democrats, Ron Bloom (appointed by Trump) reiterated his support for DeJoy and the ten-year plan this past week.

Even with Democrats in place, that alone won’t stop DeJoy. The board may be able to slow his progress once Biden’s nominees begin their tenure, but without a clear majority, there are significant limitations to what can be done. They can voice displeasure and generally make life more difficult for the postmaster general, but only a majority can remove him or prevent him from implementing the business plan that’s being developed in conjunction with one of the Democrats currently on the board.

The only remaining hope for the postal service is that Biden exercises the nuclear option at his disposal — firing the board of governors with cause and installing an entirely new board that will enable the swift removal of its saboteur. Representative Gerry Connolly, a Democrat from Virginia, has already called for the president to do so, citing the collective failures of this past year to be the only cause needed to justify it. Failing to intervene immediately means more delayed bills and prescription medicines, more 70-hour work weeks for clerks with no days off, and — perhaps worst of all — another year’s worth of eroded public trust that must be repaired. Firing the board is sure to create a legal dispute that the Democrats would need to fight in order to see it through.

In the meantime, while the administration awaits yet another peaceful resolution that is somehow always just out of reach, the workers the president swore to save will toil away. “I mean, I realized last year that the future of my career rests on Joe Biden,” the carrier from Southeastern Pennsylvania said. “That’s not really where you want to be, even if he’s better than the other guy.” Other carriers weren’t quite as cynical, but expressed similar levels of concern for the future of their jobs. “Unless there are some changes made to how things are done, at the very least, I don’t think this is sustainable,” says Joe Roman, a carrier of 26 years and nine-year shop steward for the Bloomfield branch in Pittsburgh. He’s careful to add that he doesn’t tie that directly to DeJoy, but to operations more broadly. However, other carriers Intelligencer interviewed for this story all shared a universal belief that, regardless of what his intentions or motivations are, DeJoy and his changes are the problem and nothing will be fixed until he’s removed.

Turnover for new postal workers is high, with veteran carriers and clerks citing lower pay and increased chaos as a key reason why nobody tends to stick around longer than a couple of months. It makes things harder on a daily basis, but more importantly in the eyes of carriers who have spent decades fulfilling their duty to the community, it devalues the service. “I’ve been delivering my route for a decade,” said one carrier. “I know every person on my route. That makes you take an extra effort to get them their mail. Some guy that’s in and out, and then another takes his place. I mean, that’s obviously going to impact the mission.” The inability to retain new employees exacerbates the absurd workload issues that have made 70 hour weeks the norm for carriers in high volume branches.

Postal workers who thought they were signing on for the last sure thing that exists for the American working class — a clear path towards decades of financial security in exchange for backbreaking community service — are watching in real time as it’s whittled down to another gig. “Morale is as low as it’s ever been,” says King, the union official. “I mean, we were just in a meeting last week, and they’ve got these formulas and charts and it’s just not possible. It had been bad for a little while but it just keeps getting worse for us.”