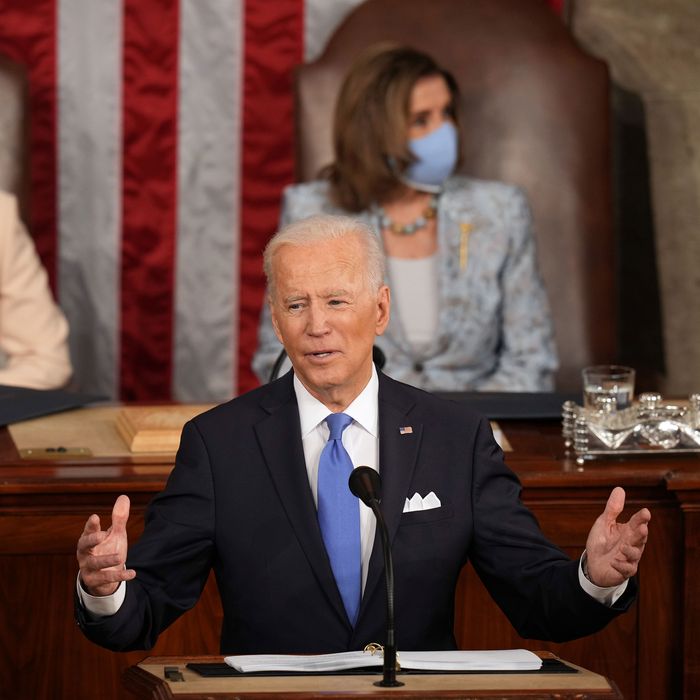

Maybe it was the shrunken, distanced audience or the masks that made Joe Biden’s first address to a joint session of Congress on Wednesday night seem especially intimate. Maybe it was his “C’mon, guys” way of describing gargantuan plans, which made it seem like he was just reminding you of something you already knew. But it was no mistake that, on the 99th evening of his presidency, Biden appeared to be talking to the room, and not always to an audience of 330 million.

Everyone there knew they were listening to a president whose politics — once cautious and compromise-forward — have been changing quickly since the onset of the pandemic, and whose initial proposals are the most potentially transformative in decades. But no one had any question that most of this change would still have to run through Biden’s Capitol Hill audience — starting with some of his own party’s more cautious members — first.

The president, speaking for over an hour and proposing trillions more in spending for infrastructure and care, made it clear that his politics weren’t going back, even with Donald Trump hardly even in the rearview mirror anymore, and even with the pandemic receding. The people are already with me, he seemed to say. Are you? To wit, he directly challenged Republicans and Democrats alike to consider the immigration bill he introduced three months earlier.

It may have been inevitable that, at the conclusion of his first 100 days in office, the Biden-as-FDR meme would go into overdrive, given the milestone’s association with Roosevelt. Witness: Axios likened the speech to a fireside chat on Thursday morning. Biden himself has leaned in to the comparison for a year, first invoking it to underscore the depth of the pandemic and economic crises, and more recently hanging an FDR portrait in the Oval Office then, on Wednesday, making Roosevelt one of just two presidents he mentioned by name in his speech.

Yet, in calling for Congress to move quickly — he urged that it take up a police-reform bill within the next month, for instance — he also appeared to recognize that amid his urgency to pass a huge array of legislative priorities, Washington’s unusually productive political atmosphere might not last long.

To the people closest to Biden, his own political shift has been remarkable to watch but not fundamentally surprising: He has always clung to the center of his party, and it has moved left rapidly, recently embracing a series of pandemic-relief policies that are widely popular with Americans on a scale that was previously unthinkable. It “reflects as much about our party as it does Joe Biden,” said Pennsylvania senator Bob Casey, a Democrat who shares a hometown with the president. Biden led off his administration the same way he led off his speech: with the stuff citizens like. “It would’ve been awfully easy to play Whac-A-Mole, [but] he has been focused, focused, focused on shots in arms and checks in pockets,” said Delaware senator Chris Coons, one of Biden’s closest allies in the chamber. “I am convinced that the politics in my caucus and in the country will sustain this scale of investment, and it will actually lead to a Biden boom,” he continued. “I think you’ll see by the third and fourth quarter of this year the economy accelerating rapidly.”

This rosy scenario likely includes passing much if not all of Biden’s infrastructure plan using budget reconciliation, almost certainly meaning without any Republican cooperation. The question, said Casey, is where senators choose to go from there. He predicted that the Senate might be able to compromise on some immigration measures and that he expected cooperation on legislation to counter China’s economic influence. Yet beyond that, he said, enacting change might require resetting the Senate’s rules, probably around the legislative filibuster that limits Democrats’ ability to pass big bills.

Coons, who maintains good relations with some Republicans and has been more skeptical of altering the filibuster, said plenty was already getting done under the national radar: Shortly before Biden spoke, Senate Democrats got three Republican colleagues to join them in rolling back Trump-era rules that had loosened restrictions on methane emissions. The day before, the Senate voted almost unanimously to take up a water-infrastructure bill. Still, no one in Washington is under the illusion that Biden’s biggest short-term proposals won’t come down to one or two votes. And no one knows what will happen to the rest of his priorities — say, voting rights, gun control, and climate — once he presumably needs 60 votes to pass anything.

At times on Wednesday, it felt like the Senate was intent on making this point for Biden. When the camera in the House chamber panned to Ted Cruz during Biden’s riff about wanting GOP support on immigration reform, the Texas Republican appeared to be dozing off. Whenever it turned to Democrat Joe Manchin, whose leverage in the split chamber is unmatched and who has threatened to slow Biden’s latest infrastructure projects, the West Virginia centrist was taking notes, betraying no emotions.

A few hours before the speech, I spoke with John Anzalone, Biden’s pollster and a longtime Democratic strategist who has recently been urging the president to make a public push for taxing the rich. Some of Biden’s advisers have recently been growing uncomfortable with the FDR comparisons. It’s understandable that Biden should want his busy first 100 days to play a big part in defining his tenure — Roosevelt’s were legacy-shaping. But they weren’t the whole story, and presidents rarely end up being defined by their first three months. If there’s a parallel between Biden and Roosevelt, Anzalone said, it’s that both men filled a void left by an unpopular, overmatched president and immediately passed major legislation to counter the day’s overwhelming disasters. But, he said, it’s important that Americans not underestimate the scale of what’s still left to be done.

We’re now watching in real time as Biden, who’s been thinking about what his presidency might look like for nearly five decades, comes to terms with what it must actually be now, after the initial flurry of action. Biden’s COVID-relief bill passed in March, but it’s unclear when his infrastructure and family plans are likely to get votes.

“Since Joe has lived so much history, and because he’s a student of history, I believe he sees this as a moment [where] he is deciding not to kick the can down the road,” said former California senator Barbara Boxer, who’s long been close with Biden. The 78-year-old president, she believes, has been reflecting on how much time has passed. She likened him not to Roosevelt, but to Lyndon Johnson. “He sees himself in these years: If ever we can do it, it’s now. There’s not going to be a ten years from now. Some younger politicians might say, ‘Well, this’ll get figured out down the road.”” Johnson jammed his changes into just over five years as president; Roosevelt served for 12.

The preliminary result is a presidency that, so far, looks little like the one Biden had envisioned even a few months ago, in ways both mundane and grand. Is he still a schmoozer at heart, making calls to old friends once his daily public schedule is through? Yes, but without the Bill Clinton–style freewheeling that’d been expected of him. Biden’s conversations seldom go too late into the night, and, some of those friends tell me, they’re quicker and more directed than they used to be. He is now the one who hangs up, with better things to do. Biden, too, had for years spoken privately of the presidency as primarily an internationally facing job, ideally consisting of frequent one-on-ones with foreign counterparts and a heavily stamped passport. Instead, he will only go to Europe on Air Force One for the first time in June, after having reminded the country on Wednesday of his conviction that international and domestic policy must work together, and of his directive to his administration to “advance a foreign policy that benefits the middle class.” On Wednesday, the jetsetting inclination peeked through: Twice, he veered off the prepared script to expound on American competition with China, first declaring an inflection point in the relationship and then reminiscing about his many hours spent and miles traveled with Xi Jinping, who he said is “deadly earnest on becoming the most significant, consequential nation in the world.”

To those closest to him, this all looks less like a reinvention of Biden than an acknowledgment of both his potential role in the sweep of modern American history — moving the country past the Trump years and actively confronting the crises he keeps mentioning — and a reaction to his office’s limitations. “Biden filled a leadership void without a doubt, on COVID and economic help, but at the end of the day it’s just the beginning,” said Anzalone. “He’s of the moment.” Increasingly, he sees it as his responsibility to remind Congress of that fact, and thus to let his colleagues down Pennsylvania Avenue know that they need to be, too.

He’s also determined not to let anyone think the moment’s changed him too much. When he stepped off the dais on Wednesday night, Biden descended to the House floor crowd to bump fists and grab elbows for the first time in over a year, his grin obvious even over his black surgical-style mask. He lingered talking to old colleagues, and even stopped to listen to a pair of freshman Republicans who’d voted against counting the Electoral College votes in January pitch him on cooperation. After a while, though, he seemed to realize he’d better get going: it was getting late, and he was due in Georgia on Thursday for a few events. One was a visit with Jimmy Carter, who he used to delight in reminding colleagues he’d been the first non-Georgia elected official to endorse for president in 1976. And then he was expected back north for the most on-brand event imaginable. He’d be capping his 101st day in office with a stop in Philadelphia, where he’d pitch his infrastructure plan at Amtrak’s 50th birthday celebration.