Last week, the first 17-year cicadas began to emerge from a band of earth draped like a sash across the middle of the country, including D.C., Tennessee, and Ohio. Since the last time we saw these bugs, in 2004, about a third of all of the carbon emissions ever produced in the history of humanity have been pumped into the atmosphere — which means the climate crisis is about one third bigger, and one third more urgent, than it was the last time we were reflecting on the surreality of glimpsing planetary history in 17-year intervals, separated by 16 years of darkness. The next time we see cicadas, in 2038, the next act of the climate crisis will have been largely written — sealing not just the fate of the Paris agreement’s optimistic 1.5-degree goal but possibly its 2-degree target as well. Whether we avoid those levels of warming — the two-degree threshold has been called “catastrophic” by scientists, “genocide” by island nations, and “death to our continent” by African climate diplomats — will be determined by the pace of global decarbonization undertaken during the life cycle of a single generation of insects. Climate change can really fuck with your sense of time. It’s why climate advocates and activists like to say, these days, that short-term commitments are much more important than long-term pledges: When it comes to avoiding once-terrifying levels of warming, there can be no more delay; if you take these temperature goals seriously, there is simply no more slack in the timeline.

For decades, the two trajectories have drifted steadily apart, with necessary emissions curves always bending immediately downward and actual emissions paths continuing ever upward. Even over the course of the pandemic, when unprecedented and exhilarating “net zero” commitments were made by Japan, South Korea, the E.U., China, and then-presidential candidate Joe Biden, clear-headed climate advocates could legitimately wonder just how different these commitments were than the ones that had been made, over and over again, in decades past. They could ask why so many of the timelines of decarbonization were so long, why so few included concrete investments to be made over the next few years, and they could demand a more honest presentation of what “net zero” really meant, since the term — especially when it came to the recent flood of corporate commitments — was often deployed as a kind of cover for the continued use of fossil fuels, assuming that emissions would be undone in the future by some as-yet unbuilt carbon-removal technology or program. The rapid decline in the price of renewable energy and the growing social pressure to take action on climate gave the new commitments a sheen of new promise. But how real was it? How much was a mirage conjured by desperate hope? It has always been easy enough to draw a line on a graph that gets you to zero emissions, though it was even easier a few decades ago, when necessary emissions cuts measured just a few percent per year. It’s a lot harder to actually build that line in the real world, with all the necessary wind and solar power, the transportation and industry infrastructure, the agriculture and land-use policy, the transportation systems and consumption changes. Hardest still, probably, is retiring fossil fuel infrastructure fast enough to make those other rollouts really matter.

But lately something does appear to have changed. Perhaps for the first time in the history of climate action, it seems that dreams of decarbonization are being actually instantiated and made concrete — and not just at prototype scale. New renewable energy capacity grew by 45 percent last year, more than half of it in the year’s last quarter — suggesting that the astonishing pace may be accelerating. In Australia, solar energy now powers more than 20 percent of homes, up from 0.2 percent in 2007, a rate of growth faster, the Guardian reported, than the one long considered a “step change” path. Vietnam has grown its solar capacity a hundredfold in just two years, making it the world’s seventh-largest solar power generator, leading Bloomberg to declare that “even countries with weak climate goals are getting swept up in the global clean energy transition.” Honda and Volkswagen have said they’ll stop manufacturing gas-powered cars by 2040. GM and Audi have targeted 2035, Volvo 2030, and Jaguar 2025. This week, Ford unveiled its all-electric F-150. It’s not even that expensive — at $41,669 the base model is only $800 more expensive than the gas version, and that’s not counting any state or federal credits. The Biden administration is debating a clean electricity standard and promising to cut the country’s emissions in half in a decade. That is very soon.

Earlier this week, the International Energy Agency added to the optimism, with the release of a report outlining a path to global net-zero emissions by 2050 — a path the notoriously conservative organization, founded to serve the oil needs of first-world economies, says is consistent with the goal of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. The report has been widely greeted by applause like that which greeted Princeton’s “Net-Zero America” study in December — both by climate activists on the left, thrilled to see an agency like the IEA acknowledge the urgency of the climate crisis and call for an end to new fossil-fuel exploration, and by energy centrists gratified to grasp what looks like a real global plan in their hands. And it is worth applauding — a road map so rapid, its vision of the future lies somewhere between the inspiring and the incredible. “Environmental anxieties haven’t toppled neoliberalism,” I wrote a few months ago, in a long essay reflecting on our new climate politics. “Instead, to an unprecedented degree, they infiltrated it.” The IEA channeling climate anxiety and paying at least lip service to climate justice in advocating for a rapid retirement of fossil fuels — this is what I meant. It’s one thing to see Sunrise calling for an end to fossil-fuel investment or the scientists of the IPCC drawing a path to net zero; it’s another to get them both from the IEA.

There are three caveats, though. First, the IEA plan addresses itself only to global energy use, which represents the lion’s share of the world’s carbon emissions problem, but not all of it.

Second, there is the report’s claim to offer a path to 1.5 degrees, when, in fact, even the optimistic scenario sketched in the report would give the world only about a 50 percent chance of limiting warming to that level. We are already at 1.2 or 1.3 degrees, which gives a sense of just how ambitious the 1.5-degree path would have to be; one estimate without any negative emissions suggests that, to hit 1.5 degrees, we’d have to zero out on emissions not by 2050, as the IEA suggests, but by 2035.

Third, there’s the work being done by “net” in “net zero.” In the IEA scenario, in 2050, the energy sector is still producing almost 8 gigatons of carbon annually, almost a quarter the amount it produces today, to supply about a fifth of global energy needs, even in 2050. This means that the IEA scenario, without relying too heavily on negative-emissions technologies, makes significant use of carbon capture, at the scale of 1.6 gigatons of CO2 in 2030 and 7.6 gigatons by 2050. Today, the total amount of carbon captured globally amounts to 0.04 gigatons — one-40th of what the IEA says is necessary by 2030, and about one-200th what it calls for by 2050. Today, there are about 15 carbon-capture projects capable of storing 1 megaton of carbon operational anywhere in the world; the IEA scenario requires building five of them every week between now and 2050.

Other challenges may prove even steeper. The IEA calls for an end to new fossil exploration or investment and no new coal plants to be built without carbon-capture capability is, perhaps, the report’s headline event — and it sets that deadline immediately, with admirable clarity, in 2021. The world is turning, as a whole, against fossil-fuel investment, but this kind of hard stop would represent a dramatic break from recent trends. Last year, in the midst of pandemic, about $700 billion were invested in oil, gas, and coal. China alone put almost 40 gigawatts of new coal power online, the equivalent of about one new coal plant each week and three times the rest of the world’s total — a pace called “runaway expansion” by an analyst at the Center for Research on Energy and Clean Air. It currently has almost 250 gigawatts of additional new coal power under development. This is just the first sign of the staggering scale and pace of the transition being described. The energy transition looks less like a global World War II–scale mobilization than climate scientists and climate activists who so often invoked the phrase long imagined; the IEA has just offered a slightly more detailed sketch of what that mobilization would actually entail, and it entails much more.

In the IEA scenario, global energy demand in 2050 is 8 percent lower than it is today, despite delivering electricity for the first time to 750 million who today don’t have it, serving the needs of a planet with 2 billion more people on it, and powering an economy it estimates will be twice as big as today’s — which means that the scenario calls not just for a “decoupling” of economic growth from carbon emissions but from energy use itself. (This isn’t quite “degrowth,” but it’s probably about as close as an organization like the IEA is going to get.) The report suggests that to bring the world into range of 1.5 degrees would require the roughly 2 billion people around the world who now cook with wood and other biofuels to transition entirely to cleaner fuels by 2030, which is to say, nine years from now. By that year, the report suggests, we’ll need to be adding over a thousand gigawatts of wind and solar capacity every year, a fourfold increase from 2020’s record pace. By 2035, no more cars with internal combustion engines would be sold anywhere in the world. This is what it takes to keep warming to what the world’s scientists have told us is a relatively workable level.

The future described by the IEA report is alluring, and not just for those of us alarmed by the threat of climate change. The energy transition would create 14 million new jobs, it says, and the work of retrofitting old buildings and infrastructure could create 16 million more. Air pollution, today responsible for roughly 10 million deaths per year, would be rapidly drawn down, with health benefits rapidly growing.

How realistic is all of this? Total capital investment in the energy transition would have to rise to $5 trillion annually. In the U.S., the figure is $800 billion each year, for 30 years — eight times what Joe Biden has proposed spending just over the next eight. That the IEA, of all forecasters, is drawing this map suggests that a transition of this speed is, perhaps, finally possible — and not just “within the laws of physics,” as Greta Thunberg often says, but within the bounds of more human laws, as well. But finally joining the race, and even starting to run, is not the same as winning it — as Bill McKibben famously put it, when it comes to climate, winning slowly is the same as losing. Seeing the path isn’t the same as taking it. And just weeks before the IEA report, a sobering alternative view was offered by another report, published by J.P. Morgan and prepared in part by notorious energy-transition skeptic Vaclav Smil, whose view of the future is shaped by the past, where such transitions have proven terrifically long and slow.

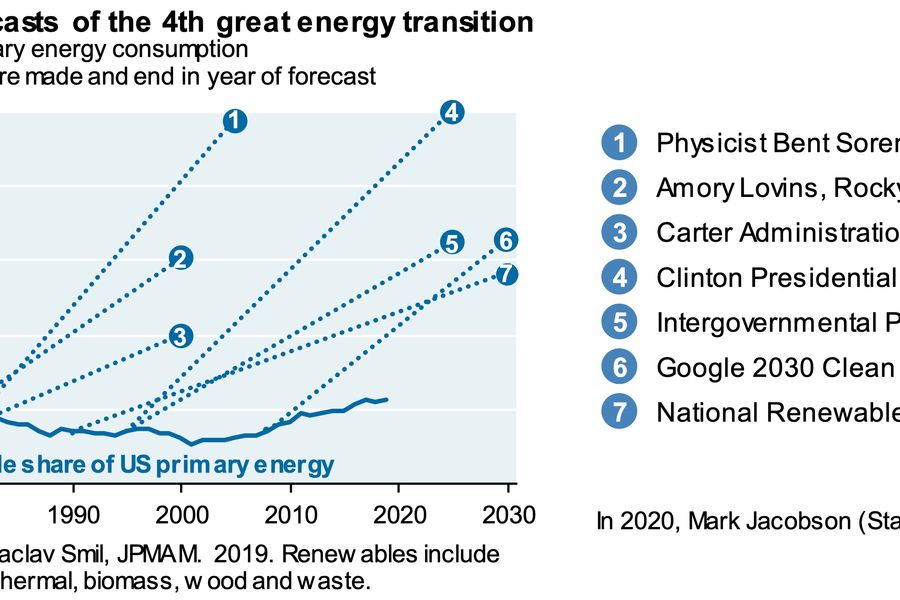

The Morgan report opens with this dispiriting chart:

It continues by mocking Will Ferrell’s Super Bowl ad, acknowledging that while Norway is “eating our lunch on EVs,” their transition is so dependent on government subsidy that a full transition to electric vehicles could make those subsidies the country’s second-largest expenditure, behind only pensions and ahead of the military, health care, and anything else you can think of. It points out that “taken together, the aggregate impact of nuclear, hydroelectric and solar/wind generation reduced global reliance on fossil fuels from ~95 percent of primary energy in 1975 to ~85 percent in 2020,” and that while total energy use has fallen in some parts of the world — Japan, the E.U. — that decline has been dwarfed by sixfold energy growth in the developing world. It expresses mostly skepticism about carbon capture and storage — criticizing this technology is a hobbyhorse of Smil’s — which is currently capable of sequestering only 0.1 percent of the world’s carbon emissions. Sequestering just 15 percent of U.S. emissions, the report suggests, would require new infrastructure larger than the country’s existing oil infrastructure, which took a century to build.

Who’s right? The disorienting truth is that they both are. Rapid decarbonization is simultaneously possible, even visible in the near term, thanks to unprecedented mobilization in recent years, and extremely hard — almost unimaginably disruptive and impossible to achieve in any technocratic, snap-your-fingers-and-the-problem-is-solved kind of a way. The energy transition isn’t a glide path, however smooth the ski slope of decarbonizaton looks on a chart drawn out to the year 2050, based on an assumption in the present that we will get there. But it also can’t be dismissed as just a presumption, or put off any longer, for that matter, while we wait for the work to grow less rugged. It won’t; just the opposite, in fact. And whatever energy and climate future that follows from here will be bounded by both sets of these facts, not just one. Mercifully, we finally have that second, optimistic set, too. The question is what we do with it.