From the time of the Constitution’s ratification until Joe Biden’s junior year of college, the United States was governed by a de-jure racial caste system that denied most Black Americans political power and economic opportunity. For this reason, America’s working class is much less white than its rich. Which means that any economic policy that takes resources away from America’s economic elite — and gives them to its laboring masses — will also, on net, transfer resources from white Americans to Black ones.

Historically, Republicans have taken pains to emphasize this fact, while Democrats have attempted to downplay it. The logic of these tactics was straightforward: The U.S. electorate is both overwhelmingly white and overwhelmingly non-rich. If non-rich white voters believe that redistributive policies take money from white people like them and give it racial others, then it will be easier for the anti-redistribution party to prevail in elections; if such voters believe that redistributive policies take money from the rich and give it to working people like them, then the pro-redistribution party will have the upper hand. Thus, in 2009, Glenn Beck derided the Affordable Care Act as “the beginning of reparations,” while Barack Obama insisted it was a means of providing health care to “middle-class Americans.”

In recent years, however, some Democrats have come to emphasize — and, occasionally, even exaggerate — the racial implications of race-neutral, redistributive policies. In the early days of the 2020 primary, multiple Democratic candidates attempted to rebrand their ideas for delivering affordable housing, baby bonds, and middle-class tax cuts as forms of “reparations.” More commonly, Democrats will make a point of spotlighting the racial-justice implications of progressive economic reforms, from universal health care to the minimum wage.

This development interested Yale political scientists Micah English and Joshua Kalla. A large body of poli-sci research had affirmed the wisdom of the major parties’ traditional messaging strategies: emphasizing that universal programs disproportionately benefit racial minorities decreases support for those programs. But perhaps times had changed. After all, the Black Lives Matter movement had mounted the most prominent challenge to racial inequality in the U.S. in a generation, and the racial attitudes of white Democrats had liberalized in response.

To test this possibility, English and Kalla took a set of race-neutral economic policies — a $15 minimum wage, student-debt forgiveness, zoning reform, the Green New Deal, and Medicare for All — and then presented them to voters using three different arguments: one that emphasized the policies’ class implications, one that emphasized their impact on racial justice, and one that emphasized both. To enhance the validity of their experiment, they used Democratic politicians’ actual rhetoric for each of these arguments.

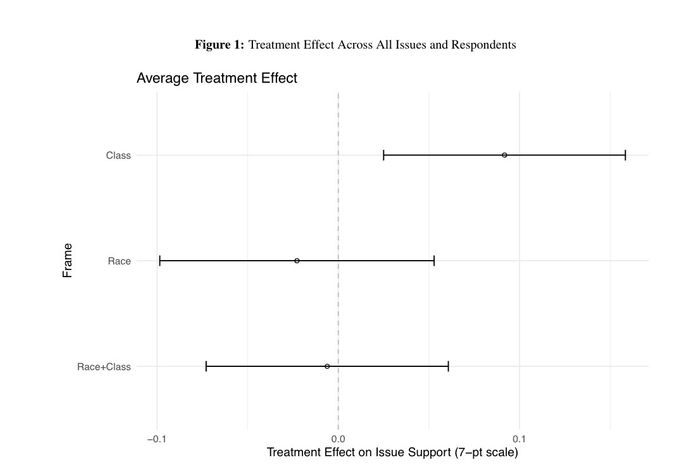

Their findings confirmed conventional wisdom: The class message tended to modestly increase support for progressive policies, while arguments involving race slightly reduced support for them, though not by a statistically significant margin.

Notably, while Black voters were responsive to both race and class-inflected messages, they too found the class-only message most persuasive.

The paper’s findings shouldn’t be overinterpreted. A single survey experiment demonstrating persuasion effects this modest can’t settle any debates by itself. And it’s hard to know how well such a study approximates the impact of political messaging in the real world. Still, the fact that it comports with the bulk of existing research on this subject, and with the tactics of political practitioners in both parties until very recently, lends some credence to its results. In my view, the paper was a worthwhile — though not dispositive — contribution to our collective knowledge of one narrow question of public opinion.

But some saw it differently.

Don’t shoot the message-tester.

Ian Haney López, a professor of public law at Berkeley and chairman of the AFL–CIO’s Advisory Council on Racial and Economic Justice, took exception to the study and the media’s coverage of it.

López argues that the paper reaches strong conclusions on the basis of weak evidence: Given that the class message only “weakly” outperformed the racial one, he contends that the authors went too far in concluding that “linking public policies to race is detrimental for support of those policies.” His chief substantive complaint, though, concerns the paper’s neglect of the Race-Class Narrative (RCN) — a messaging strategy that he co-pioneered. The RCN framework counsels Democrats to weave forthright acknowledgments of racism into a message of cross-racial class solidarity; to tell voters, in López’s words, “racial division is the main weapon in the class war the rich are winning.”

The RCN strategy has attracted significant interest and investment in progressive circles. And so López had some cause for fearing that Kalla and English’s test of a “race and class” message — which merely adds a racial message to a class one, rather than specifically framing racism as a weapon in the one percent’s class war — would be mistaken for a test of his own favored framework.

But López did not confine himself to narrow quibbles with the paper’s methodology or requests for further research. Rather, he suggested that the paper should be understood as a brief for one side in the Democratic Party’s “civil war” over racial issues — namely, the side that opposes “working for racial justice for communities of color.” As López wrote in a series of tweets:

The paper is garnering attention not because its evidence is especially strong. Even the authors conclude that their actual results are statistically weak. (“Overall, we find that the class frame weakly dominates both the race and race-class frames,” page 6). Rather, it’s garnering attention as ammunition in a civil war that’s been raging among Democrats since Republican dog whistling began in the 1960s. Some Dems urge directly challenging political racism, and more broadly working for racial justice for communities of color.

Others say calls for racial justice alienate white voters. They urge a race-silent approach, typically one that focuses on class. This is NOT a debate between racial justice and economic populism. It’s a debate about whether to address — or instead ignore — racial justice. By testing “class” or instead “race” frames that Democrats use to promote various policies, Kalla and English stake a place in this debate. Unfortunately, they did so with a paper that is flawed, weak, and likely to engender confusion.

Here, López posits a binary: On one side are Democrats who want to directly challenge political racism by foregrounding the racial implications of race-neutral policies and work “for racial justice for communities of color”; on the other side are people who oppose both of those things.

This is unfair. “Should Democrats work to redress racial oppression and inequality?” is a question of values. “If Democrats emphasize that progressive economic policies redress racial inequality, will that make it easier or harder for them to win elections and then pass those policies?” is a question of fact. If one posits that a “race-silent” message will enable the Democratic Party to secure power and increase funding for affordable housing, Medicaid, and K-12 education in disadvantaged districts — while foregrounding race will enable Republicans to win power and defund those public goods — then advocating for a “race-silent” message is, in practice, “working for racial justice for communities of color.”

In other words: A person’s ideological commitments cannot be derived from their position on empirical questions of tactical efficacy. The disagreement between López and progressives who found the Kalla-English paper useful is not about whether Democrats should pursue racial justice, but about how they should go about doing so.

López should be sensitive to this distinction between tactical judgments and ideological commitments. After all, his own preferred messaging strategy involves downplaying racial difference. In the RCN, racism is invoked and condemned. But it’s also framed primarily as an impediment to preventing the rich from exploiting “white, Black, or brown” workers alike, not as an obstacle to rectifying the historical injustices inflicted on nonwhite Americans specifically. It’s a bit “all lives matter,” in other words.

Can we infer from this that López wants Democrats to prioritize issues that concern all workers to the exclusion of those that concern Black and undocumented ones? Of course not. He is putting forward a theory about optimal messaging, not a declaration of his deepest ideological commitments. In their paper, Kalla and English are doing the same thing.

Democrats’ political timidity is an obstacle to racial justice. But their struggle with unenlightened white voters is a bigger one.

All this said, the concern that research like Kalla and English’s might lead Democrats to forsake the interests of the marginalized is reasonable. If merely touting the anti-racist implications of child-care benefits is politically hazardous, Democrats might reason, then taking action on racial issues that a majority of Americans don’t have a direct stake in — such as citizenship for the undocumented or housing discrimination — must be even riskier. I don’t think this necessarily follows; how messaging impacts public opinion, and how legislative action does, are two separate questions. But Democrats have subordinated minority-group interests to political expediency in the past, often in ways that were more substantively harmful than electorally beneficial. And President Biden’s recent flirtation with retaining Donald Trump’s refugee cap indicates that the impulse to placate reactionaries — at the expense of the vulnerable — is still alive within the party.

Yet this impulse is also less potent today than it’s ever been. López’s characterization of the Democrats’ internal tensions is largely anachronistic. No significant faction within the party is pushing for a rightward lurch on racial issues (though some are trying to slow its leftward drift). In 2021, the primary obstacle to legislative progress toward racial justice is not the Democratic leadership’s reluctance to tackle that subject. Joe Biden has decried racial inequality in every major speech he’s given as president. House Democrats have already passed bills on the highly racialized issues of police reform, immigration, and voting rights. These measures are inadequate in various ways. But they all would constitute advances — if there were enough Democratic votes in the Senate to pass them.

Alas, by all appearance, there aren’t.

Congress’s upper chamber underrepresents Black voters and wildly overrepresents rural white voters (who, in the aggregate, have less than progressive views on racial issues). The erosion in rural white support for Democrats over the past two decades has left the party with a massive structural disadvantage in the race for Senate control. As a result, despite winning the national popular vote by a large margin in two consecutive federal elections, Democrats boast only a bare, 50-vote Senate majority. If Joe Manchin means what he says, this will not be a large enough majority to pass any major legislation on voting rights, immigration, policing, housing discrimination, or any other non-budgetary racial-justice issue.

This is the fundamental challenge facing the progressive movement. Unless Manchin & Co. have an epiphany — and decide to abolish the filibuster, ban gerrymandering, and grant statehood to D.C., Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands — the existing Democratic coalition’s structural disadvantages will get worse before they get better. As is, Republicans are overwhelmingly likely to retake the House in 2023 on the strength of partisan redistricting alone. Meanwhile, if Democrats do not add new states, their odds of retaining the Senate past 2024 will be slim. Many of the party’s most vulnerable, red-state incumbents only survived 2018 because it was a wave election in which the nation as a whole favored Democrats by eight points. The only way these senators can survive 2024’s general-election environment is if they — and their party — gain ground with white Trump voters. (Increasing turnout among nonwhite voters probably is not a viable alternative due to their underrepresentation in the Senate, and in any case, nonvoters aren’t much more reliably progressive than the existing electorate.)

Progressives should do everything they can to persuade moderate Senate Democrats to make Congress more representative of the national electorate. But the default assumption must be that no democratizing reforms will be passed. In that scenario, there will be no path to passing progressive federal legislation unless Democrats increase their support in places that voted for Donald Trump.

Thus, few questions are more pertinent to the project of racial justice in 2021 than, “How can Democrats advance policies that aid nonwhite people without triggering white backlash?” If our goal is to fend off reactionary rule and make life easier for disadvantaged communities, then we must not stigmatize open inquiry into that question.

Messaging strategies should be judged by their efficacy, not their ideological convenience.

López, and others who favor race-conscious messaging, have a coherent theory for why their approach is optimal: In the real world, major policies that disproportionately advantage nonwhite people will be racialized no matter how Democrats talk about them. The right will make sure of that. Given this reality, getting ahead of such racial demagoguery — by recasting racism as a tool of elite domination, or else, directly challenging white identity itself — will be more effective than pretending there is no racist elephant in the room. Moreover, even if tiptoeing around the prejudices of white swing voters were expedient in the short-term, such a strategy would leave the barriers to thoroughgoing reform in place. White supremacy has always been the chief obstacle to social democracy in the United States. And its legacy does not disappear when Democrats close their mouths about it.

But there is a coherent, alternative view. David Shor, and other so-called “popularist” progressives, have a theory that goes (roughly) like this: Democratic politicians have little ability to change the views of voters who are not already strong Democratic partisans. The median voter in the race for Senate control is a 55-year-old, non-college-educated homeowner who pays only a little attention to politics, and voted for Trump at least once. Joe Biden is not going to change this person’s fundamental beliefs about race or the nature of American society. Rhetoric about how the rich use racism to divide working people is too abstract and ideological to register with them; they just don’t think about politics in those terms. To the extent that Democrats can win them over, it’s by telling them, in simple language, how the party’s policies will make their lives easier. If this voter is thinking about Medicare and stimulus checks when they head to the ballot box, Democrats have a chance; if they’re thinking about race or immigration, all is lost. Therefore, Democrats must exercise message discipline and work to heighten the salience of their most popular economic ideas — because, for the most vulnerable in our society, the costs of allowing Republicans to retake power are immense. And we are at a point in history when progressives have no choice but to play some defense. Eventually, demographic churn will erode the GOP’s structural advantages and the grip of white supremacy on American society. But until the boomers’ share of the electorate falls to a safe level, we face a real risk of right-wing authoritarianism. The left’s avant-garde should pursue long-term public-opinion change by writing op-eds and propagandistic TV shows; Democrats should tailor their rhetoric to the tastes of unenlightened white people.

Both these views seem facially plausible to me, and I think there may be ways to reconcile some of their respective insights. To the extent that Democrats must choose between them, however, that choice should be dictated by evidence. The Race-Class Narrative is an intriguing strategy. But the publicly available evidence for its potency appears to consist of studies conducted by the concept’s proponents, using outdated methodologies.

Some progressives reject the enterprise of polling and message-testing on epistemological grounds; they contend that political reality is too complex — and Democratic messaging choices, too irrelevant to political outcomes — for such research to be of much use. I think this view is quite reasonable, if suspect in its ideological convenience (if message-testing is dead, everything is permitted).

But those who believe that there are more and less effective ways for Democrats to communicate with the public — and that polling can tell us useful things about which is which — must favor methodologically rigorous studies over ideologically pleasing ones. To do otherwise is to put one’s own comfort above the well-being of the marginalized groups who have the most to lose from reactionary rule.