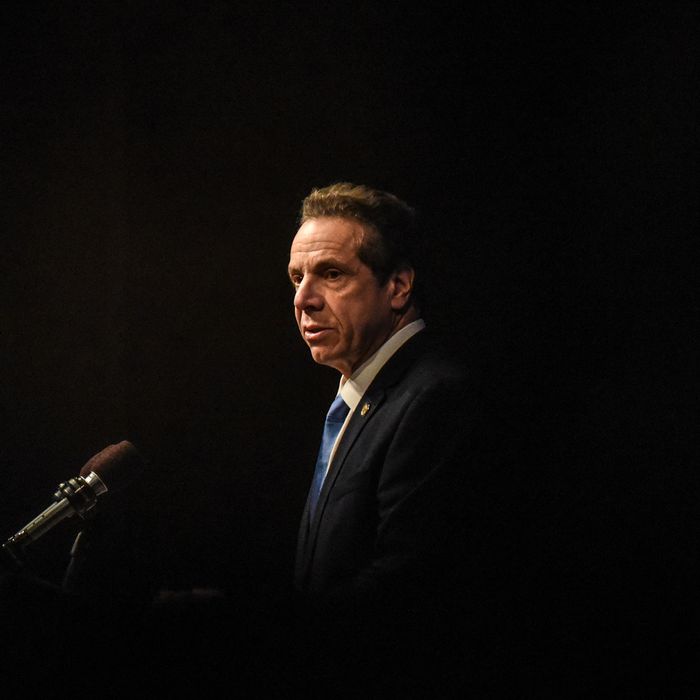

The possible unraveling of Andrew Cuomo’s tenure as governor has always been a story about power. What is his dominance built on? How is it performed, how is it abused, and can it ever be brought down? On Tuesday, New York State Attorney General Letitia James released a report that is both a spotlight on the source of Cuomo’s power and a test of its endurance: an astonishingly damning document detailing the stories of 11 women, nine of them state employees, who have accused Cuomo of, variously, making inappropriate comments about their dress and appearance, kissing and touching them without invitation, inculcating a professional culture predicated on fear and intimidation, and, in one case, groping one of their breasts.

The fallout was immediate and intense. President Joe Biden called on Cuomo to resign. Multiple federal and state lawmakers from his own party — including Jay Jacobs, head of the New York Democratic Party, who had defended Cuomo throughout this embattled year — said the same. The New York State Legislature will pursue an impeachment inquiry against Cuomo, and his reign as governor could end in its hands. Or sooner — several people close to Cuomo told The City that his resignation was “no longer a matter of if he will resign, but when.”

For now, how and if Cuomo actually goes down remains an open and intriguing question for reasons that were on display in his swift and aggressively dishonest response. The governor conveyed that he had no intention of stepping aside via a vile prerecorded video statement in which he spun deeply intoned denials of the accounts presented in James’s report. His lawyers then released a printed rebuttal to the investigation, a document that was short on text and long on bizarrely inapt photographs of politicians hugging hurricane victims and of Cuomo hugging and kissing his father, mother, and daughter — as if that had anything to do with accusations that he kissed his employees. His reflexive refusal to cede even a millimeter of his authority echoed the unwavering stance he has taken in response to the wave of investigative reporting that has broken since this spring: about his alleged harassment of employees and his administration’s cover-up of nursing-home deaths from the pandemic. And while he may not be long for the governor’s mansion, he has made it this far.

James’s report is breathtaking in its scope and precision. It contains 168 pages of testimony and more than 1,000 footnotes of corroboration and reference, rooted in interviews with 179 people and a review of 74,000 documents. In contrast, Cuomo’s denial is all shambolic denial and posturing, a chaotic attempt to make his own reality, without regard to the strength or number of contradictory stories being told about him. It is a mirror of Cuomo’s conception of power, which until now has had no limit and has not been bound by reason or honesty, fact or merit.

Much of what is detailed in James’s report reflects the apparent pleasure the governor took in leaving women he encountered in professional contexts confused, discombobulated, and ultimately powerless to object. Multiple people also testified about how Cuomo and his senior staffers fostered a workplace environment where regular cruelty and threats of retaliation held employees in a state of terrified paralysis and where young women were openly appraised based on their looks and not their professional worth.

The document includes the previously unreported story of a state trooper whom Cuomo met at an event in November 2017 at the RFK Bridge. He hired her for the Protective Services Unit despite the fact that she did not have the required three years of experience. This trooper told investigators that the governor went on to make unwelcome remarks about her attire, personal life, prospective marriage, and sex drive and that he kissed her and touched her, including on her stomach, in ways that made her feel profoundly uncomfortable. Her experience corresponds closely to that of other women in the report, some of whom I reported on back in March, including Kaitlin, who told of how, after meeting Cuomo briefly at a party, she was recruited to work for him directly. She was then subject to unwelcome personal attention, including an instance in which he had her bend over his computer at an awkward angle while he watched her look for car parts on eBay.

The report includes the claim of Lindsey Boylan, a former Cuomo employee, that he once suggested to her, as his dog was pawing her, that “if I was the dog, I’d mount you too”; an energy-company employee’s story of how, at a public event, Cuomo traced the letters of the company logo on her T-shirt by pressing his fingers into her breasts; and an executive assistant saying that Cuomo once grabbed her breast under her shirt and on another occasion touched her butt “in a way that was not clear whether he had intended to do so.” One staffer described how he would come by her desk and hold her hand for uncomfortably long periods of time, until she became flustered and blushed, noting that she felt her reaction was “part of the point” of Cuomo’s behavior, which she understood was designed to make her feel “small” and “uncomfortable.”

These are all dynamics created by Cuomo to perform and thus maintain control over situations and people, to reinforce the relative impotence of those on whom he had professional or political influence — which, as governor of New York State, was pretty much everyone.

James’s report also finds extensive evidence of Cuomo’s office’s attempts to retaliate against those who defied that influence by coming forward with complaints about the treatment they experienced, especially against Boylan, whose public accounts of Cuomo’s harassment were among the earliest. Cuomo is revealed to have first drafted himself, and then brought on a team of senior advisers to help him write and edit, a letter (never published) that was meant to impugn Boylan’s credibility, while his staffers attempted to leak her confidential personnel file to the press to the same end.

The report is unequivocal. Cuomo, though, in his response, not only sounded undaunted by the seriousness of its findings but also replicated much of the performance of dominance it chronicled. He simply rewrote the narrative, mischaracterizing the allegations against him in a plaintively voiced pantomime that bore little relationship to reality or what he is actually alleged to have done.

“Women occupy the most senior posts in his administration, and he has more senior women in his administration than any previous governor of this state,” his lawyers’ statement reads in part, despite the fact that the number of women on his team was never questioned and that some of the most senior of them are named as having participated in the retaliatory cover-up and ill treatment of complainants.

“He is informal with his staff and banters with all employees … regardless of gender, in an effort to bring collegiality and levity to their high pressure and demanding positions,” the report went on. “He is interested in their lives. His close staff members have become his family, which is not uncommon when working in politics. President Barack Obama’s White House staffers went ‘everywhere in cliques’ and lived together in Washington, D.C. … Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer similarly describes his staff as a ‘family.’”

This is non sequitur nonsense. No one has complained about Barack Obama or Chuck Schumer groping their employees’ breasts or asking them inappropriate questions about their dating life or commenting on their sex drive. Nor has anyone suggested that Andrew Cuomo fostered a professional environment that had anything to do with familial closeness or unbridled levity and warmth; rather that he has built a workplace on backbiting toxicity, cruel power hierarchies, and abject mistreatment.

“It would be a pure act of insanity for the Governor — who is 63 years old and lives his life under a microscope — to grab an employee’s breast in the middle of the workday at his Mansion Office,” reads Cuomo’s defense. But Cuomo and his team also worked to actively cover up the number of people who died of COVID in nursing homes in New York while winning an Emmy and making a multimillion-dollar deal for a book about his management of COVID. It would be insanity to believe that that happened, too, but it did. And it’s not actually insanity; it’s power and how it covers for itself in ways that bear no relationship to truth or even plausibility.

“There are generational or cultural perspectives that I hadn’t fully appreciated,” Cuomo said, explaining why he might not have known it wasn’t okay to kiss or touch or make inappropriate comments to female employees. But Cuomo was in his 20s, and just four years out of law school, in 1986, when the Supreme Court decided unanimously that sexual harassment at the workplace was illegal under Title 7 of the Civil Rights Act. Just five years later, Cuomo would have been 33 when Anita Hill testified during Clarence Thomas’s confirmation hearings for the Supreme Court that Thomas had harassed her when they worked together, cementing a broader popular understanding of sexual harassment. And of course Cuomo was just about to turn 60, and was governor of New York, in October 2017, when reporting on movie producer Harvey Weinstein’s serial sexual predation and workplace sexual harassment precipitated a global reckoning about sexualized power abuses. That was the very month Cuomo allegedly asked Lindsey Boylan, on a flight, whether she wanted to play strip poker. And it was after the Me Too reckoning that another seven of the 11 women cited in James’s report claim he behaved inappropriately toward them.

Cuomo isn’t generationally confused; he is lying, and James’s report catches him out over and over again. He told investigators that he didn’t refer to his top female staffers as “Mean Girls” even when they told the same investigators that he did. He said in his prerecorded statement that he asked Charlotte Bennett, a survivor of sexual assault who alleges that Cuomo sexually harassed her, “questions I don’t normally ask people … to see if she had positive, supportive dating relationships.” But according to the testimony of many, he asked lots of his female employees about their dating relationships. Cuomo told investigators that he didn’t sing the song “Do You Love Me?,” by the Contours, to Bennett (“I don’t even know that song,” he said in his testimony), but they have a recording of him singing it … to Charlotte Bennett.

Cuomo lies because that is part of how he construes his authority: that having power means getting to control the story and how it is told. He gets to name the characters, using nicknames for female employees like “Bun” and “Sponge” and “Sweetheart” and “Mingle Mamas.” He gets to characterize them as “fragile” and “delicate” (what he said about Bennett) and “jealous” (how he wanted Executive Assistant No. 1 to make her friend and colleague Alyssa McGrath feel). If he gets to control the story, it enables him to fend off or shut down other versions of the story that are inconvenient to him, that might chip away at or threaten his authority.

As the attorney general’s report put it, “The Governor’s blanket denials and lack of recollection as to specific incidents stood in stark contrast to the strength, specificity, and corroboration of the complainants’ recollections.” In other words, his version of events is built on air: made of spit and chicken wire and disdain for those who dare to question him.

That Cuomo’s accounts are fictional, his power based on theatrics over substance, press conferences over policy, doesn’t make them less real. After all, all kinds of actual, lived inequities — political, professional, economic, racial, and gender — are built around invented hierarchies and caste systems with zero basis in merit or science or fact. Yet even though they, too, are made of chickenwire and spit, they become thick and unbreakable, have measurable impacts when it comes to housing, health, education, safety, security, and public estimations of basic human worth.

Donald Trump lied about his businesses and taxes and Barack Obama’s birth certificate and powered a successful presidential campaign on those fabrications. He responded to multiple allegations of harassment and assault by stalking Hillary Clinton around a debate stage, and he beat her. These baseless performances of dominance have nonfictional, measurable, tragic consequences.

In his knee-jerk move to defend himself, Cuomo is counting on the fact that in this country you can, to some extent, retain control by denying facts and observable, quantifiable realities. You can, for example, claim that a vacant Supreme Court seat can’t be filled in the last year of one president’s term, then claim that another vacant Supreme Court seat can be filled in the last months of another president’s term. These can be claims made of air and fevered partisan malevolence, but they can also result in a very real 6-3 Court that will have a very real ability to alter the lives of very real people. You can make up fictions about stolen elections and uncounted ballots and voter fraud, and if you are in a position of political or legislative authority, you can transform those fictions into real laws that will successfully suppress a franchise in order to keep you in your position of political or legislative authority.

When you have power, even if it is predicated in part on empty performance and dishonesty, you have power. And you can wield it to make it easier for you to retain it, and to protect you from any incursion on it.

It has already worked for Cuomo, who simply plowed through the spring storm by spewing lies and vitriol and demanding official inquiries, the results of which he is now rejecting, denying, and impugning. And as long as he bullishly maintained his power and position, he could continue to use it to intimidate those who might be in a position to curtail it. Letitia James’s report includes the story of how, in the weeks after the harassment allegations came to light, Melissa DeRosa, one of the governor’s top aides, had Larry Schwartz, the state’s “vaccine czar,” call county executives to ask them if they still supported the governor, reporting their responses back to DeRosa. The county executives, the report found, “reasonably felt that Mr. Schwartz had significant authority and influence over supplemental vaccine requests and other issues like the location of vaccine sites, at a time when County officials urgently wanted to get vaccines to their constituents.”

The authority that Cuomo and his top staff had preserved in the spring by refusing to concede anything in the face of carefully reported, corroborated accounts of abusive behavior and harassment, as well as votes of no confidence from their own party, enabled them to just … keep their authority. And thus to maintain their ability to continue to pressure people who might have dared to weaken that authority.

The performative insistence on maintaining a stranglehold on power can work. It worked for Donald Trump, who was impeached but remained the president. It worked for Cuomo’s Democratic brethren Ralph Northam and Justin Fairfax, governor and lieutenant governor of Virginia, both of whom were asked to step down by multiple members of their party after Northam was found to have done blackface in medical school and Fairfax was accused by two women of sexual assault. Both men simply preferred not to; they just kept going, kept their jobs, kept their power.

It has thus far worked for Cuomo, despite his party asking him to step down five months ago. But there is reason to imagine a world in which this stops working, in which it might even backfire. Because in the attorney general’s report, which in its breadth and detail could be powerful enough to lead to Cuomo’s forcible removal from office, there are instances in which Cuomo’s reflexive lying worked not to protect him but to produce more testimony against him.

Executive Assistant No. 1, the woman who claims that the governor asked her about her divorce and groped her breast and grazed her butt, had sworn, she told investigators, that she would take her recollection of these events “to the grave.” But when she watched Cuomo’s March 3 press conference, at which he asserted that he had never “touched anyone inappropriately,” the baldness of the lie was too much for her. She became upset; colleagues noticed; she confided in some of them who then reported her story to senior staff.

Similarly, the energy-company employee who said that Cuomo pressed his fingers into her chest, tracing a T-shirt logo, told investigators, “My coming forward is a direct result of the Governor’s March 3 press conference at which he said, ‘I never touched anyone inappropriately. He is lying again. He touched me inappropriately.’”

This is the question in front of Andrew Cuomo and New York: Will the old paths to maintaining power — dishonesty, threat, performed dominance — continue to serve the powerful? Or are we able to imagine an end to their utility?

What reliance on those old tactics does not account for are subordinates, employees, colleagues, journalists, and attorneys general who, for whatever reason, have ceased to be convinced that the persistence of top-down, suffocating power is inevitable — who understand that, increasingly, they have power of their own.

More on Andrew Cuomo

- The Heavy Hitters Who Could Run to Succeed Eric Adams

- Eric Adams’s Strategy to Hang On

- Andrew Cuomo Wants the Kind of Redemption That Comes From Winning an Election