A bitter hypocrisy of progressive New York is that we boast endlessly about our history as an immigrant-friendly, forward-looking gateway to the American Dream — but in reality, many of the city’s newcomers are treated with a shocking level of contempt and indifference that can, at times, prove deadly.

In recent years, news outlets have chronicled the gruesome toll suffered by our city’s immigrant workers. Every year, some fall to their deaths off scaffolds and down elevator shafts at construction sites. Others get killed while delivering food or working in massage parlors. Nail salons are rife with exploitation and subminimum wages. Conditions in some domestic settings are so cruel that advocates compare them to modern slavery.

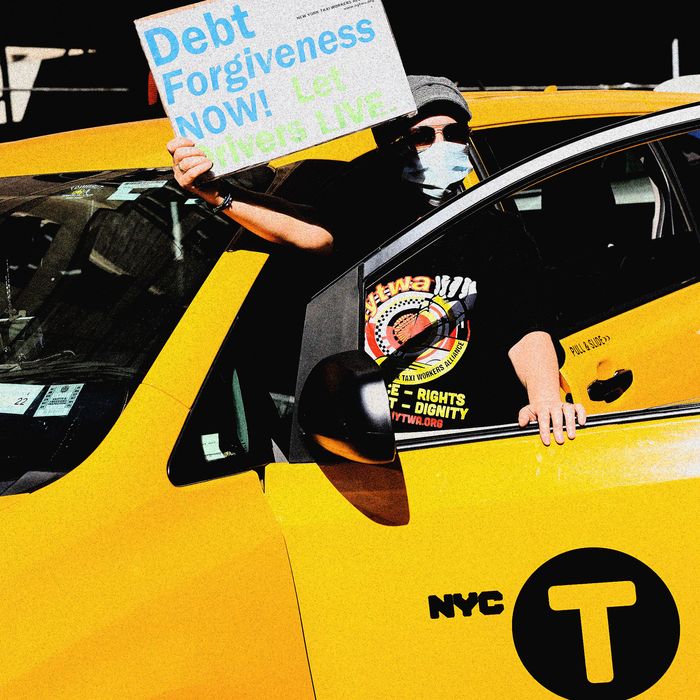

“Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,” reads the noble verse at the base of the Statue of Liberty. It so happens that a tired, poor mass of taxi drivers is currently huddled at the corner of Broadway and Murray Street, a few steps from the west entrance to City Hall. They have set up a 24-hour picket line, and this week raised the stakes by announcing a hunger strike.

It is a desperate cry for help from city policies that have left thousands of drivers facing financial ruin, including bankruptcy, foreclosure, eviction, and homelessness.

“I have been down to the protest six, seven, eight times standing with these drivers, 94 percent of whom are immigrants,” Assemblyman Zohran Mamdani of Queens told me. “In New York City, politicians love to talk about how they love immigrants, how they love the fabric of our city, how they love taxis, they sell taxis as the symbol of this great city. And yet, when it comes to the drivers themselves, they’re being cast aside and told, ‘We hope you can float under these hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt.’”

The roots of the taxi-medallion crisis date back more than 80 years, long before ride-hailing apps like Lyft and Uber. In the 1930s, the city faced a glut of taxi drivers whose huge numbers made it impossible for anybody to make a decent living. New York’s solution was to create an exclusive city license to legally pick up passengers on the street, with license holders given a metal medallion affixed to the hood of their taxi.

For decades, the city carefully limited the number of medallions in circulation, freezing the total at around 13,000 — the same number in effect in the 1940s — which steadily drove up the value of those scarce licenses. A financial bubble began to grow after the year 2000, fueled by unscrupulous lenders who convinced thousands of drivers to borrow ever-larger sums and bid up the price of medallions at city-run auctions, on terms that would spell disaster if medallion prices ever cooled off.

Immigrant drivers took on huge debts and often doubled down by refinancing on even worse terms. All the while, the city’s Taxi and Limousine Commission happily watched — and encouraged — the soaring medallion bubble. Between 2001 and 2013, the price of a medallion increased by 500 percent, according to the report of a City Council task force, peaking at more than $1 million per medallion in auctions that raised hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue for the city.

Ride-hailing app companies launched in New York in 2011 and began ramping up in huge numbers a few years later — but the city failed to contain or control the sudden arrival of more than 100,000 cars. The surge in new drivers undercut the market for metered taxis as riders flocked to e-hail services, and the value of yellow-taxi medallions crashed. It’s hard to be sure what a medallion is worth now — auctions were discontinued in 2014 — but estimates of $100,000 are common, down from about $965,000 in 2014.

It was a slow-motion crisis. Taxi drivers had sounded the alarm early on, to no avail.

“The city has, through the Taxi and Limousine Commission, a responsibility to uphold the economic stability of all the licensees. They failed in that responsibility,” a medallion owner named Carolyn Protz told me back in 2017 at a roundtable of taxi drivers. “There just isn’t enough business to justify that number of cars. The city’s responsible for this. They have no answer.”

Satwinder Singh, a medallion owner and driver, said the same thing. “How do you compete? It’s like 13,000 [medallions] compared to 60,000 [app-hail] cars. When we purchased our medallion, there was a right that when anybody has his hand up [to hail a cab], that’s my ride — I paid for it,” he said. “Our rights are being betrayed or sold, given to others without paying anything.”

Bhairavi Desai, executive director of the New York Taxi Workers Alliance, says thousands of drivers are now on the brink of ruin. “The average debt is around $550,000, and there are about 6,000 individuals who own the medallion. And half of them are actually owner-drivers,” she told me. “Along with carrying forward this average $550,000 debt, they’ve also been incurring on average like $25,000 in credit-card debt and having to pay for rent and groceries using credit cards because every other dollar from the income is going towards the medallion’s debts.”

The strain of owing half a million dollars while being lucky to clear $200 a day after expenses has taken a grim toll. In 2018, eight drivers committed suicide, with many of them citing crushing, unpayable debts.

One of those who died that year was Kenny Chow, a driver swamped with debt who left his car near Mayor Bill de Blasio’s Gracie Mansion residence and threw himself into the nearby East River, where he drowned. His brother, Richard Chow, is also a heavily indebted driver who is among the protesters outside City Hall.

“When he committed suicide he owed $580,000 to the bank,” Chow said of his brother. “So he lost everything. He lost retirement, he lost investment. He lost everything. He took his own life in the East River and I’m very frustrated, I’m heartbroken. So that’s why we are not only fighting for my debt. We are fighting for 6,000 medallion owners and their families. So we can make a livable income and we can survive.”

The de Blasio administration has set up a $65 million relief fund that drivers call inadequate. The city plan offers $20,000 grants for drivers to use as a down payment on renegotiated loans that would shave up to $200,000 off a driver’s existing medallion debt.

Desai and the drivers say that’s not nearly enough.

“TLC has said it’s going to be on average $200,000 relief. Which doesn’t mean much when you’re left with $300,000 to pay off,” she said. “What the city has now, it’s just the wrong approach. It does not solve this crisis, it’s a bridge to bankruptcy and utter financial ruin…for an entire workforce whose crisis the city itself is responsible for. They have a moral obligation to fix it.”

Mamdani lays the blame at City Hall’s feet.

“Our city government actively marketed these medallions to this driving population as, quote, ‘better than the stock market,’” he said. “The City Council itself found that $500 million would be an appropriate amount of money to provide relief to drivers. And instead, the city is putting forward $65 million. We are willing — and I say this as a legislator and in concert with other legislators — to take whatever actions necessary, because accountability is going to come from Mayor de Blasio, because it is his decision on whether or not to provide these drivers what they deserve.”

De Blasio shows no sign of reconsidering his relief plan.

“I’ve been asked many times before, could we do a full bailout? We cannot. We’ve been really clear about that,” he said at a press briefing this week. “That’s hundreds of millions of dollars and has a lot of other ramifications for other folks who have gone through tough situations and could ask for a bailout. We are really trying to be as helpful as we can in a smart way.”

In other words: Tough luck, immigrants. The drivers are heading into their second month of street protests, hoping not to join the long list of newcomers who have gotten a raw deal from a city that loves to boast about its hardworking immigrants.