Obviously, I’m anxious about why I’m being profiled,” Matt Taibbi said at the end of our phone call this summer, which had already lasted an hour and a half. He was on vacation with his family. The day before, they went on a whale watch. “One thing that’s a little irksome, again, in my actual personal life, I could not be more the opposite of that …”

That could be, if you’ve read Taibbi over the last quarter-century, loaded with possibility: the acidic brilliance or the antic humor or, more recently, the savage scorn he has shown for “cancel culture.” There is a public Taibbi and a private Taibbi, and the more you speak with him and others who know him, the more you begin to understand the difference. The public self is not a lie or a performance — it’s just, in private, Taibbi is not going to punch you in the face, like his prose might suggest he would.

Not that Taibbi is apologizing for his combative posture. “I’m certainly not going to feel guilty for having success at Substack for saying things I believe are true. I’ve been very consistent over the years in saying the same things,” Taibbi said. “I feel pretty strongly that the only thing that’s changed is that the New York media world once agreed with the things I was saying, and now they don’t.”

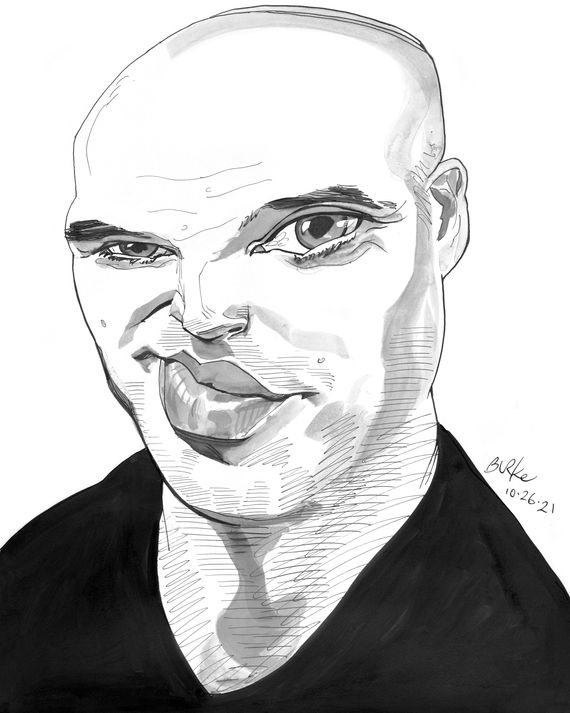

If you follow the media and the internecine warfare that’s liable to consume any given afternoon on Twitter, you probably have an opinion about Matt Taibbi. Few journalists, in polarized 2021, divide the New York-D.C. nexus more. Taibbi is viewed in more liberal quarters with increasing suspicion bordering on outright disdain, a remarkable development for a magazine star once considered Rolling Stone’s successor to Hunter S. Thompson.

Taibbi is — or was, depending on your view — one of the most celebrated investigative journalists of his generation. In the 2000s, during the height of the financial crisis, he was lauded for his incisive, bilious takedowns of Wall Street — particularly Goldman Sachs as the infamous “vampire squid.” He won a National Magazine award and regularly appeared on cable television, grinning like an impish schoolboy even as his hair receded. In college journalism classes throughout the country, Taibbi was a rare hero, Bob Woodward shed of pomposity. He was the ultimate insider-outsider, a chronicler of presidential campaigns and corporate malfeasance who lost none of his edge even as his star burned brighter.

Today, Taibbi is flush. He is no longer affiliated with Rolling Stone, but his Substack newsletter, TK News, is one of the most popular on the site, boasting more than 30,000 paying subscribers. Which means, at $50 a pop, he easily can clear $1 million annually, making him a member of the one percent. In addition, he hosts a popular podcast, Useful Idiots, with the comedian and filmmaker Katie Halper, where the two debate hot-button media issues and interview unconventional leftists like Chris Hedges, Adolph Reed, and Dennis Kucinich.

Raising three children in tony Mountain Lakes, New Jersey, Taibbi is more than content with his current lot. The pandemic has kept him at home — otherwise, he said, he would have traveled extensively throughout 2020 and 2021 — filing his distinctive mix of reportage and punditry. At 51, he should be entering the glorious middle phase of the prestige journalist’s lifecycle: escalating praise, escalating awards, a steady march toward media canonization.

None of that is coming anytime soon.

“I think he’s gone off the rails,” said Doug Henwood, a longtime progressive journalist who once counted himself among Taibbi’s admirers. “Now I just don’t know what the hell he’s going on and on about. He’s obsessed with stupid shit.”

What happened to Matt Taibbi? Everything or nothing, depending on your vantage point. Taibbi is, arguably, as ribald and fearless as ever. It’s just that his targets and topics have begun to shift. He does not write as much on Wall Street or corporate skullduggery anymore, preferring to train his sights on the campus left and the talking heads at MSNBC. Taibbi’s defenders say he hasn’t changed. Rather, it’s the world that has grown more illiberal and hysterical.

“I think, roughly speaking, there are two kinds of journalists — one type wedded to a partisan faction or ideological identity and the second devoted to a more journalistic ethos,” said fellow Substacker Glenn Greenwald. “Oftentimes, the people who are in the first group confuse those in the second group with being part of their group. Matt has always had a journalistic ethos, always questioned orthodoxies and pieties.”

“I think that our business, for being packed with so many radicals and liberals, is inherently conservative,” said Jack Shafer, Politico’s media columnist. “When somebody does something differently, it rankles people.”

Politically, Taibbi describes himself as a “run-of-the-mill, old-school ACLU liberal” who counts Bernie Sanders among the few politicians he actually admires. “The only thing I would say that’s different about my political thinking — and it has nothing to do with policy and politics — suddenly I’m getting along better with people who are Republicans,” he said.

Like Christopher Hitchens, Taibbi has a singular ability to infuriate the left. His most viewed Substack post, published in June 2020, remains “The American Press Is Destroying Itself.” Lately, he has blasted away at NPR and other left-leaning media, the “vaccine aristocrats” who shame the unvaccinated, popular anti-racist authors like Robin DiAngelo, and those who hope Facebook and Twitter will take far more aggressive action against lies and hateful rhetoric spread by the far right. Not long ago, he offered a defense of Tucker Carlson. FiveThirtyEight, the high church of bloodless empiricism, recently lashed Taibbi for promoting the “baseless conspiracy theory” that a drug called Ivermectin can treat COVID-19. (Taibbi successfully won a correction, with the website conceding it “mischaracterized” his stance.)

Taibbi’s critics view him as a reporter turned red-pilled culture warrior chasing subscriptions — or worse, a middle-aged male no longer at the vanguard, aggrieved that younger journalists are now leading the fight for justice. “One of a crew of a dozen white guy contrarians in media,” said the journalist Wesley Lowery.

The liberal-left especially loathes the way Taibbi equates the right- and left-wing media. His second-most recent book, Hate Inc., features Rachel Maddow and Sean Hannity on the cover together, and argues that both sides have played a role in polarizing the country and stoking hate. Taibbi has gone as far as to argue that Fox News, the propaganda arm of the Republican Party that is still the ratings king, “no longer represents real institutional political influence in this country anymore. The financial/educational/political elite with all the power is on the other side and I think they’re the people to be worrying about.”

Taibbi’s reputation these days is inextricably tied to Substack. There is, of course, no single style of Substack writer (I write a Substack newsletter myself), but the platform has attracted numerous media dissidents — including Bari Weiss, Andrew Sullivan, Matt Yglesias, and Greenwald — suggesting a market need that isn’t being met by the traditional press.

Where these writers converge — and where outrage for their cohort simmers among many liberals in media and politics — is in their willingness to excoriate what the essayist Wesley Yang, another prominent Substacker, has termed “successor ideology.” At their core, all of these writers, Taibbi included, share a discomfort with the identity-based politics that has consumed much of media and academia over the last few years, particularly in the wake of George Floyd’s death and the mass protests against police brutality that followed. Some have written critically of two of the best-selling anti-racist authors in America, Ibram X. Kendi and Robin DiAngelo, arguing that they are steering America down a course of unsustainable sectarian warfare, divorced from a humanistic tradition of open debate and respect for free speech. Taibbi has called DiAngelo, the White Fragility author, a purveyor of “tricked-up pseudo-intellectual horseshit.”

Many of them have also argued that the authoritarian threat posed by Donald Trump and his Republican Party is overstated. Many bemoan what they see as an overly woke, censorious culture in media and politics, with younger millennials demanding fresh limits on speech. For Taibbi, tech censorship has become an overriding concern. He runs a regular feature on his Substack called “Meet the Censored,” where he interviews various journalists and thinkers, a sizable number on the left, who have been casualties of Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter’s crackdown on disinformation in the Trump era.

Taibbi is reluctant to categorize himself as a culture warrior. “A lot of criticism has centered on this idea that I’m only writing about cancel culture and that sort of thing, but that’s actually not the case,” Taibbi insisted, pointing to his review of Christopher Lasch’s 1979 tome, The Culture of Narcissism, and an old-fashioned investigation into predatory student loans.

But Taibbi is quite obviously preoccupied with cultural affairs, especially in media. “The culture-war stuff is popular,” he conceded. “I do find it extremely interesting. A lot of these developments came up in the last couple of years — they’re the background for why I came to Substack in the first place — and involve this growing discomfort I had with Rolling Stone that started with Russiagate and then became this thing where I was just increasingly aware of this self-censorship going on. You’re increasingly worried about every little thing you say. Every day, there’s this new taboo in blue-leaning media.

“I was covering the campaign and having discussions with people on the bus. They were saying we have to start doing the job differently,” Taibbi recalled. “You started to see it, the moment where being interested in the news in a voyeuristic way disappeared and you had to take an interest as a participant in what was happening so that a lot of things that attracted me to journalism, that detached sense of humor you get in newsrooms — that vanished overnight. Suddenly people are taking sides and putting their thumb on the scale.”

Taibbi locates the shift in mainstream media to the 2016 presidential campaign. He cites Jim Rutenberg’s column in the Times as something of a starting gun. Rutenberg, then the media columnist, wrote in August of 2016 that if you were a journalist who believed Trump “is a demagogue playing to the nation’s worst racist and nationalistic tendencies, that he cozies up to anti-American dictators,” you had to “throw out the textbook American journalism has been using for the better part of the past half-century, if not longer, and approach it in a way you’ve never approached anything in your career.”

But what if Trump wasn’t a fascist, after all? What if he was just a lousy, unhinged Republican president? When do journalists slam the emergency button? “During that early Trump period, I felt continually that I was put in the difficult position of having to either co-sign an erroneous piece of anti-Trump propaganda or be accused of being a Trump-lover,” Taibbi said. “I certainly lost a lot of audience during those years, and like Glenn was the subject of a lot of criticism from within the business, for not being sufficiently aggressive in my coverage of Trump. However, that had nothing to do with how I felt about him, and everything to do with an increasing unease with the way he was being covered.”

The irony is that Taibbi built his career stomping on the textbook of American journalism. “After the 2008 crash, when the mainstream papers kept telling audiences how complicated the subprime mess was, I attracted a lot of readers just by saying simple things like, ‘Actually, this stuff isn’t that hard, these people are basically just thieves,’” he said.

“I’ve always rejected the objective style personally, preferring just to be open about my biases and thoughts,” Taibbi added, noting that he agrees with younger journalists, like Wesley Lowery, that the traditional neutral voice or “view from nowhere” is outmoded. Taibbi sees his work these days as being inspired less by Hitchens and Thompson than H.L. Mencken, the essayist and cultural critic known for, among many things, his satirical reporting of the Scopes Monkey Trial. “Especially in an atmosphere where people feel constrained and afraid to say certain things, I think there’s a role for someone to try to do what Mencken did, which was basically undress everyone and skewer sacred cows,” he says. “Mencken would have had a tough time in today’s environment.”

The way that the mainstream media has erred, in Taibbi’s view, is by growing too overtly ideological — by becoming, in at least one important respect, too much like Matt Taibbi. “A lot of my readers are people who talk about how they can’t read the Times or listen to NPR or watch MSNBC because they’re so tired of the leaden messaging,” he said.

Taibbi’s tortured relationship with the media, swerving between its golden boy and one of its fiercest antagonists, is his birthright. The only child of Mike Taibbi, a veteran broadcast journalist who worked at NBC and ABC, he grew up outside Boston, often feeling alienated. His parents split up when he was young, his mother largely raising him while going to law school at night. As a teenager, he wanted to be a novelist, falling in love with Russian writers like Nikolai Gogol and Mikhail Bulgakov. “If you need 100 things to be a good fiction writer, I’m probably missing seven of them, the seven really important ones,” he says. “I don’t have a good ear for inventing details.”

Behavioral and academic difficulties landed him in a private school, Concord Academy, where his parents hoped he’d shape up. “I was confused, lonely, had an authority problem, had really lost my way in adolescence, and this was a solution for all of us,” he said. Upon graduating from Bard College in 1992, he headed to Russia, in the wake of the Soviet Union’s collapse, with a plan to string for newspapers while writing his great novel. The novel didn’t arrive and Taibbi, going door-to-door at all the foreign bureaus in Moscow, wasn’t published much elsewhere either. Eventually he was offered a real job at an expat paper, the Moscow Times.

It was in Russia, in the late 1990s, where Taibbi had his first taste of renown and infamy. A fellow American named Mark Ames recruited him to help edit a newspaper called The eXile. Decades later, the newspaper retains it notoriety, making the more fire-breathing alternative weeklies in America look like church newsletters in comparison. Regular columns included Ames’s “Death Porn,” which rehashed stories of horrific murders and suicides from police reports and Russian media. One of the most reviled (and anticipated) Ames features was “Whore-R Stories,” in which he hired prostitutes and wrote about them.

There were the pranks that anticipated Taibbi’s later attitudes toward the respectable press. Furious that the Times’ Michael Wines had endorsed the Kosovo war and conducted a softball interview with Vladimir Putin, Taibbi and Ames conspired to fill a thermos with horse semen, put it into a baked pie, and smash him with it in the face. Taibbi did the honors, writing it all up with a photo of a forlorn Wines, crust and filling stuck to his mug.

Occasionally, the two men tended bar at an infamous local hangout, the Hungry Duck, where only women, on so-called “ladies night,” would be let in from 6:30 to 9. They drank for free. “There were 250 beautiful women in this packed bar and completely drunk and in would charge all the men, paying a massive cover fee to get in,” Taibbi remembered. “After that, it was a complete bacchanal, you had fights, people having sex on the floor.” In a 2010 account of The eXile years in Vanity Fair, the Hungry Duck was described as a “vile flesh pit” where the deputy head of a Moscow police unit, drunk out of his mind, could empty his pistol into the ceiling and make everyone lie on the floor for three hours.

Ames did speed and Taibbi developed a heroin addiction. “I was never an IV user but it was bad,” he said. “I had problems with opioids throughout my life.” He kicked the habit when he came back to the States and found he didn’t have a dealer anymore. “You’ve seen Trainspotting?” he asked. “It was hard.”

But there was journalism, too — enough of it that The eXile, in its relatively short existence, could make its mark. Taibbi wrote on the IMF’s policy in Russia, Moscow prisons, and labor strikes. He spent time among crime bosses, cops, and corrupt politicians, writing an illuminating series in which he lived as an ordinary Russian for weeks at a time. He was a miner and a bricklayer. He attended a Moscow high school. Meanwhile, the international cognoscenti and many of the Americans working at prestige newspapers in Moscow were convinced that American-style free enterprise and democracy were afoot. As decided outsiders, Taibbi and Ames could effectively puncture the narrative that post-Soviet Russia was a Western success story.

“He wrote some insane shit but they basically had it right,” said Ben Smith, the New York Times media columnist. “The Washington consensus was that Russia was becoming a democracy; The eXile portrayed it as going to hell.”

Taibbi and Ames would have a bitter falling out; the two haven’t spoken in almost 20 years. Taibbi left The eXile several years before it folded in 2008, heading back to America to further his journalism career. Ames declined to comment for this story. “This sounds too depressing,” he said. “Good luck with it.”

Other eXile alums weren’t interested in speaking much either. “I’ve said everything I wanted to say about Matt in what I’ve written about him,” said former eXile editor Yasha Levine, who recently criticized Taibbi for belonging to the “new reactionary right.” “Matt and his career trajectory are just too sad and pathetic to waste any more of my time on. American political culture is cursed. What the fuck is the point?”

Taibbi’s work at The eXile would come back to haunt him decades later, with the Me Too movement in full swing. Just as Taibbi was preparing to promote his new book on the police killing of Eric Garner, I Can’t Breathe, passages from a 2000 book co-written by Taibbi and Ames on The eXile years resurfaced. Both men, especially Ames, trafficked in twisted satire. Passages written by Ames described purported sexual harassment at The eXile and portrayed Ames as having sex with a 15-year-old girl, coercing a woman into having an abortion, and raping other Russian women. Both men insisted none of it was true, but accusations of misogyny spread across the internet.

In 2017, as the firestorm built, Kathy Lally of the Washington Post wrote that she and other female journalists who served as correspondents in Moscow were subject to boorish writings and pranks from Taibbi. “The eXile’s distinguishing feature, more than anything else, was its blinding sexism — which often targeted me.” (Lally declined to comment for this story.)

Taibbi offered a lengthy Facebook apology in wake of the controversy while denying he sexually harassed anyone. “As a young man, I wrote and said some very dumb and hurtful things,” he wrote. “But it was never more than that. I know the list of revealed harassers is growing, but I am not on that list, nor should I be. I belong to a much bigger group. I was young once, and a jerk. And I am sorry for that.”

The damage, to some extent, was done. Taibbi’s publisher, Penguin Random House, dropped him. His relationship with Rolling Stone would continue, but not for much longer. Elizabeth Spiers, a longtime media observer and founding editor of Gawker, argues Taibbi’s experience with Me Too precipitated his fierce attacks on the left. “It tapped into some white male grievance things he has,” Spiers said. “If you look at his critiques more recently, they’re knee-jerk, on the other side whatever the left is interested in right now.”

The controversy still rankles Taibbi. “I wrote some absolutely disgustingly offensive stuff, but particularly in my case this was almost 100 percent a pose, as I’m kind of a recluse and wallflower in my private life,” he said. “The drug aspect was real, but a lot of the rest of it was done for effect, to be deliberately offensive, because the conceit of The eXile was that it was the unvarnished tourist guide for the plundering Ugly American — if conquistadors wrote Time Out, for instance.”

Back when Taibbi was interviewed for the Vanity Fair piece on The eXile, he grew so enraged with the journalist, James Verini — Verini called Taibbi and Ames’s eXile book “redundant” and “discursive” — that he cursed Verini out and threw coffee in his face.

An older Taibbi, still not feeling much warmth for Verini, mostly agrees with his assessment of the book. “It was a complete misread of what the average American would care about,” he says. “It’s kind of embarrassing to look back on now.”

Rolling Stone had written a feature on the eXile in 1998 and one their editors at the time, Will Dana, was keeping an eye on Taibbi. Dana believed, ultimately correctly, that Taibbi could be a star there if given the leeway to write and report in his distinctive register. Soon the former enfant terrible was reporting from Katrina-ravaged New Orleans and filing scathing, must-read dispatches from the 2004 presidential campaign.

Taibbi the magazine employee was reserved, reliable, and never blew a deadline, according to Dana, who recalled he brought flowers for the fact-checkers after a piece was headed off to print to thank them for their efforts. “He never played the star diva card,” Dana says. There were moments, certainly, when he could have: By 2011, protesters at Occupy Wall Street were toting around vampire-squid puppets, directly inspired by his reporting.

Dana is one of the old Rolling Stone hands, along with former executive editor Eric Bates, who count themselves among Taibbi’s steadfast admirers. Bates, who now edits Insider, recalled that Taibbi was one of the only journalists he had worked with who had a significant impact on the broader culture. “We had interviewed Obama a number of times and we would get reader questions asking, ‘What’s he like?’ We started to get that with Matt. ‘What’s he like?’ No one does that with a writer. Most people in the world aren’t curious about what a writer is like as a person.”

Taibbi briefly left Rolling Stone in 2014 to run Racket, an investigative magazine published by the billionaire Pierre Omidyar, but clashes with management led to his return to Rolling Stone. Into 2021, his podcast, Useful Idiots, was still affiliated with the magazine. And then, suddenly, it wasn’t. The reasons seem to be bound up with Taibbi’s general disillusionment with the industry.

“One of the moments that solidified in my mind the difficult path I’d have going forward in mainstream media, and that pushed me toward the decision to do Substack full-time, came when I did a campaign piece on Biden for Rolling Stone,” Taibbi said. “I was noticing what everyone else saw, that the man was having trouble remembering things, among other issues. I called back some of the medical sources who were glad to violate the ‘Goldwater rule’ against diagnosing people from afar to talk to me about Trump being crazy, just to ask for their assessment of Biden. None responded, and one literally hung up on me. Even off the record they wouldn’t talk about it. It hit me in that moment that Trump had so fundamentally changed the business that even sources were behaving differently, and I’d have to adapt one way or the other.

“I definitely became embittered toward mainstream colleagues during these years, who piled on and accused me of being a secret Trumper and a Putinite and all of these things, just for not signing off on hot takes like: Trump is a literal Russian spy, Trump is clinically insane, Trump is Hitler, America is literally a fascist state, etc.,” he continued. “In my mind a lot of them were making very cynical decisions just to ride the Resistance train to easy money by pumping up these hot-take crazes.

“I could have done that — with my background, I could easily have come up with some cockamamie Russia angle and probably even scored a big advance writing a book with a backwards ‘R’ in the cover headline and an upside-down St. Basil’s growing out of Trump’s head or whatever — but I didn’t do that, obviously.”

Taibbi isn’t wrong. The “grift” of the Trump years broke both ways, with six-figure book contracts routinely minted for any reporter or pundit who could hustle up gossip on the most deranged White House in anyone’s memory. One lament, though, among those who believe Taibbi has lost his way, is that the game he chases today might not be worth it. Instead of throwing hedge-funders up against a wall, Taibbi is excoriating the media for failing to report on the fact that, despite the FDA and NIH advising against treating COVID patients with Ivermectin, some doctors are prescribing the drug off-label. Taibbi’s argument — that the news media can report health-care authorities are warning against Ivermectin as a treatment while acknowledging the drug is out there and being distributed — isn’t wrong. It’s more a matter of how one of the most talented reporters of his generation should wield his formidable powers in this uncertain age.

Taibbi believes the American media needs another Mencken, but there are enough heterodox thinkers that operate, in the realm of Substack at least, to flay whatever the predominant and misguided groupthink might be. Takedowns of NPR and the Democratic Party are not especially scarce. What is far more of an endangered species is the bold investigative reporter with enough time and money to produce the kinds of stories that terrify politicians and shift the Zeitgeist — the reporter that Taibbi used to be.

It’s a notion Taibbi, prone to more self-reflection than his public persona suggests, considers. “Obviously what I’m doing on Substack is different than what I’ve done in my career. I’ve spent most or all of that time, 30 years, doing the slogging investigative or pseudo-investigative kind of reporting,” he said. “I’ve earned a little time to not do that for a year or two.”