Bemoaning the Democrats’ own-goals has become blue America’s favorite pastime. The moment the party attained power last November, depressive progressives and anxious centrists began lamenting its impending self-defeat. And not without cause.

The Democrats face massive structural disadvantages becauseof their reliance on wildly underrepresented urban-dwelling constituencies. Unless the party makes significant inroads with white rural voters, it will struggle to compete for Senate control in the latter half of this decade. Yet the Democrats’ messaging and governing choices do not evince much recognition of this challenge. The party could use its tenuous grip on federal control to make Senate representation a bit more democratic (and, likely, Democratic) by giving statehood to Washington, D.C., and any U.S. territory that wants it. And it could have made banning gerrymandering in House elections its first order of business upon taking power.

But it didn’t — because Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema would rather preserve the filibuster than their party’s capacity to pass federal legislation. And the Democratic leadership has few mechanisms for coercing a change in this preference. Thus Republicans may have already secured themselves a House majority come 2023 on the strength of gerrymandering alone.

To give their party a remote chance of competing on this tilted playing field, the Democrats’ disparate factions must subordinate their own interests to the common (partisan) good. The party’s right flank has declined to do so. Instead, it has vetoed the most politically expedient item on Biden’s agenda — empowering Medicare to drive a hard bargain on drug prices — along with a long list of popular tax hikes on the wealthy. Together with moderates’ demands for deficit neutrality, this forced the president to slash the price of his domestic agenda in half.

At that point, it was in the party’s interest to narrow its ambitions. But Democratic lawmakers have disparate pet policy projects. And they were not willing to subordinate their personal causes to the higher good of substantively sound, politically expedient legislating. So now Democrats are on the cusp of enacting many temporary, half-baked policies (one of which will increase child-care costs for middle-class families), instead of creating a few permanent, fully funded programs.

Finally, as “popularists” have emphasized, some progressives have a penchant for speaking in esoteric abstractions better suited to dissertations than stump speeches. And left-wing lawmakers occasionally embrace politically toxic causes that have no prospect of congressional passage, thereby imposing a political cost on their party for no (obvious) substantive benefit. So the Dems are not in full array.

But neither is the GOP.

In blue America’s internecine squabbles, combatants often conjure a ruthlessly disciplined and/or politically ingenious GOP as a foil for their hapless party. Popularists will pressure Democratic activists with anti-majoritarian demands to emulate their GOP counterparts, who (supposedly) do not hound Republican candidates to publicly affirm their commitment to unpopular causes. Progressive skeptics of the median-voter theorem, meanwhile, will point to the GOP’s success at winning elections while associating itself with many profoundly unpopular ideas as proof that ideological discipline is for suckers; “vibes” rule everything around us.

Both these claims are overstated. It’s true that coal-and-gas magnates do not attack GOP candidates for promising to deliver “crystal clean water and air.” Rather, cognizant of the median voter’s distaste for being poisoned, such polluters let Republicans say what they must to secure power, then quietly cash in their political capital once the EPA is in their party’s hands. And yet it is also true that conservative activists have forced every Republican with national ambitions to kiss the ring of the most unpopular president in American history, voice opposition to popular social programs, and perennially champion tax cuts for the wealthy.

The GOP has managed to remain nationally competitive while broadcasting these messages. And it’s possible that the right’s superior gift for associating its adversaries with “bad vibes” is one reason why. Yet it’s also the case that Republicans have abandoned a long list of conservative policy commitments in deference to political blowback, from Social Security privatization to banning gay marriage to Obamacare repeal.

At the same time, the party has paid a substantial political price for its stubborn commitment to upward redistribution and authoritarian demagoguery. After all, the GOP has lost the popular vote in seven of the past eight presidential elections. Republicans do not possess a secret formula for keeping all party-aligned activists on message, nor a surefire means of manipulating mass opinion. It’s just very good at appealing to rural white people. And rural white people boast disproportionate power over U.S.-election outcomes. In other words: The right is playing politics on easy mode.

In truth, the Democrats’ lack of partisan discipline isn’t rooted in their coalition’s peculiar pathologies but rather in the inherent weakness of American political parties. Our nation’s parties have always been weak, relative to those of Europe, since our parties are highly decentralized. But American parties have grown even weaker over the past half-century. The expansion of primary elections eroded party elites’ control over nominating processes, and thus their leverage over members. Campaign-finance reforms shifted power over funding away from formal party leaders to corporate PACs and ideologically motivated big-dollar donors. The rise of digital media drastically lowered the costs of entryism (i.e., of taking over a party through infiltration) while increasing the difficulty of elite gatekeeping. And decades of working-class wage stagnation, failed wars, and financial crisis reduced the public’s trust in party Establishments. In this context, leadership has relatively few mechanisms for forcing members to toe a party line.

This is just as true on the right side of the aisle as it is on the left. Mitch McConnell and Kevin McCarthy cannot stop Congresswoman Lauren Boebert from likening Ilhan Omar to a suicide bomber, nor can they prevent Marjorie Taylor Greene from condemning Boebert’s subsequent apology.

GOP leaders cannot stop this largely because they cannot dictate the outcomes of Republican primaries. And this weakness has cost the party. Tea Party Senate candidates helped keep Democrats in contention for upper-chamber control over the past decade. And as Ross Douthat recently argued in the New York Times, the GOP’s unruliness is presently jeopardizing its “golden opportunity” to secure political dominance.

With just a few concessions to political expediency, the Republicans could soon become America’s majority party. The Democrats’ grip on socially conservative nonwhite voters is loosening. And November’s gubernatorial election in Virginia suggests that the GOP could claw back a significant number of Romney-Biden voters by nominating standard-bearers who are not transparently sociopathic. National polls show the GOP commanding plurality support in the congressional generic ballot. If the party moderated even slightly on fiscal policy, took a less conspicuous approach to undermining democracy, and picked its “culture war” battles more carefully (by, say, assailing “critical race theory in schools” but not the existence of American Muslims), it might just win the popular vote in the next two federal elections.

And since the Electoral College, Senate, and House are all biased toward the GOP, such victories would translate not merely into a Republican trifecta, but one with massive congressional majorities.

Fortunately, corporate Republicans are more invested in minimizing their patrons’ tax burdens than maximizing their party’s power. And many authoritarian Trumpists care more about titillating conservative media consumers than keeping the Democratic Party in the wilderness. So a “popularist” turn in Republican politics is unlikely. After all, the relatively moderate Glenn Youngkin only won the GOP gubernatorial nominating contest in Virginia because it was conducted at a convention, through ranked-choice voting (as opposed to a primary election).

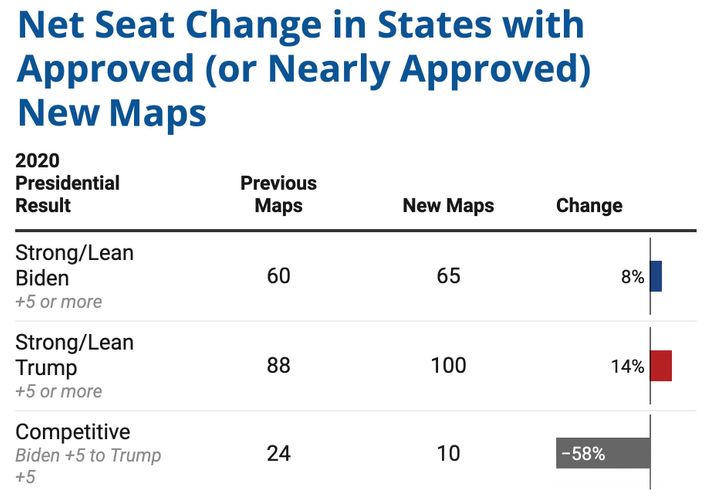

What’s more, the GOP’s structural advantages encourage its indiscipline. This is true at an almost mechanical level. Republicans’ dominance of the redistricting process means that the GOP will (almost certainly) have more House members in the next Congress. But it also means that that the party will have fewer House members who are accountable to closely divided electorates. As Dave Wasserman notes, across the 20 states that have completed maps, the number of competitive districts has fallen by 58 percent.

Meanwhile, given the biases of the Electoral College and Senate, the party could nominate a Trump-Boebert ticket in 2024 and still have a decent shot at winning full federal control. In an era of weak parties, the only plausible impetus for concerted ideological discipline is serial electoral defeat. By all appearances, that is not something that the Republican Party needs to worry about.

Thus the Republicans are in disarray. That isn’t enough to keep them out of power. But if Democrats get their own house in order, it might be enough to keep things interesting in 2024.