The Democratic Party faces many structural challenges. As its support base has grown more educated and urban, the congressional map has grown increasingly biased against its coalition. Meanwhile, the decline of ticket-splitting and the nationalization of political media have made it more difficult for the party’s candidates to compete in the right-leaning, rural states that enjoy outsize representation in the U.S. Senate. Thanks to the vagaries of the Electoral College, Joe Biden will need to win the popular vote by about four points in 2024 just to have a better-than-even shot of retaining the presidency.

But Democrats do have one tailwind at their backs: demographics. America’s rising generations are less white, religious, or conservative than any of their predecessors. The biases of America’s legislative institutions may be on the GOP’s side, but time is on the Democrats.’

Or, so we like to tell ourselves. In truth, a close look at last year’s election results suggests that Democrats shouldn’t rest their hopes on demographic change.

Late last month, the Democratic data firm Catalist released a pair of state-level autopsies for the 2020 election. One used voter file data to dissect the returns in Nevada, the other did the same for Wisconsin. The reports aren’t devoid of auspicious tidings for Democrats. The party did continue to dominate with voters under 30 in 2020, winning about 60 percent of that cohort’s votes in both states. To the extent that millennials and zoomers retain their present partisan leanings, demographic trends will eventually redound to blue America’s benefit.

Yet Catalist’s data also suggests that, in the near term, Democrats may face some significant demographic headwinds in both the Sun Belt and Rust Belt. To see why, consider these four findings:

(1) Democrats are losing white working-class supporters to the GOP; also, death.

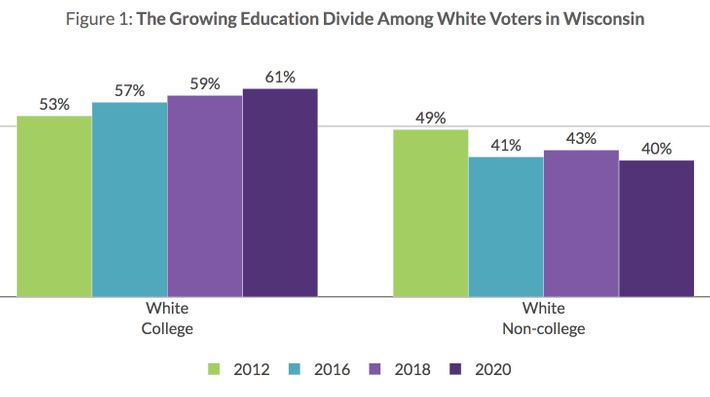

The Democratic Party has been bleeding support among non-college-educated whites for decades now. Nevertheless, the party has remained competitive in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania — three heavily white working-class states that have been integral to its Electoral College majorities in recent years.

One reason for this perseverance: White non-college-educated voters in the Rust Belt have historically voted to the left of their demographic nationwide. As Catalist notes, working-class whites in Wisconsin are about “2 to 3 percentage points” more Democratic than they are nationally.

Unfortunately, this relative liberalism is partly the vestige of a bygone era. It derives in no small part from organized labor’s erstwhile strength in the state, and an older generation of working-class whites, who came of age at a time when the Democratic Party was more closely associated with their communities.

In Wisconsin, 47 percent of whites 65 and over voted for Biden in 2020; among whites between the ages of 45 and 64, that figure was 41 percent. This discrepancy wasn’t new: In each of the last four presidential elections, white seniors in Wisconsin have voted to the left of the state’s white middle-agers.

Thus, as older Wisconsites pass from this mortal coil, white working-class voters in the state are growing less exceptionally liberal. In 2020, Democrats still enjoyed a higher level of white working-class support in the Badger State than in the nation as a whole. But the demographic actually trended away from Democrats more in Wisconsin than it did nationally: On the national level, Democrats gained a point of vote share from white non-college voters between 2016 and 2020; in Wisconsin, they lost a point.

A similar pattern prevails across much of the secular, post-industrial North. In some heavily white blue-collar parts of Maine and Michigan, senior citizens actually vote to the left of those under 30.

In Wisconsin, fortunately, young white voters are more Democratic than middle-aged ones. So, in the long term, generational churn may turn the Badger State a darker shade of blue. In the near term, however, such churn is poised to erode the Rust Belt’s remnants of labor liberalism.

(2) Elevated turnout among nonwhite voters made Nevada’s electorate more diverse — but no more Democratic.

As Democrats lost support in the upper Midwest, many of the party’s pundits and politicos began advocating for a “Sun Belt strategy.” Specifically, such Democrats argued that the party should put less emphasis on persuading white working-class voters in the Rust Belt and more on mobilizing nonwhite voters in the relatively diverse states of Florida, Georgia, Arizona, Texas, North Carolina, and Nevada.

In 2020, Democrats put considerable resources into that project. And by several metrics, it was a success: Nonwhite turnout increased considerably between 2016 and 2020. Had that not happened — which is to say, had turnout surged only among white voters last year, while Black and Hispanic voters turned out at 2016 levels — Donald Trump would still be president.

This said, the returns on mobilizing nonwhite voters in the Sun Belt were smaller than anticipated; because newly activated nonwhite voters were more Republican than expected.

In 2020, there were only two states where Joe Biden failed to improve on Hillary Clinton’s margin four years earlier: Florida and Nevada. In both of those cases, the Democratic ticket’s underperformance derived from an erosion of Hipsanic vote share, in a context of elevated turnout.

Between 2016 and 2020, Nevada’s electorate became two percentage points less white. Meanwhile, Biden won a higher share of white voters in the state than Clinton had four years earlier. And yet the Democrats’ margin of victory in the Silver State remained steady at 2.5 points, as the GOP gained significant ground among Black and Hispanic Nevadans:

This decline in the Democrats’ share of the nonwhite vote was likely, in part, a product of heightened turnout. Americans who have not previously participated in elections tend to be less politicized than those who vote regularly. For that reason, it is likely that formerly nonvoting, nonwhite Americans are less settled (and more random) in their partisan leanings than those who’ve long participated in electoral politics. Thus, as irregular Black and Hispanic voters entered the electorate in large numbers, the Democrats’ margins with those demographics waned.

(3) Democrats lost more support among young Hispanic voters than among old ones.

Notably, the Democrats’ problem with newly activated Hispanic voters was not limited to older generations. In fact, the party lost more support among Hispanic voters under 30 than among those over 65; relative to 2016, the former swung nine points away from Democrats, while the latter shifted just three points.

Younger Hispanics were still more Democratic than older ones in Nevada, according to Catalist. In Pew Research’s national data however, the younger a Hispanic voter was in 2020, the more likely they were to vote for Trump. Hispanic voters under 30 gave the Republican 41 percent of their votes, while those 65 and over gave him just 35 percent.

These findings suggest that the rising generation of Hispanic voters may be less reliably Democratic than the party’s strategists have assumed. This wouldn’t be entirely surprising. To the extent that younger Hispanic Americans are more assimilated into American culture (and/or white identity) than their forebears, their relative conservatism would be consistent with the generational drift of past immigrant groups.

(4) Democrats were already losing ground with Hispanic voters in 2018.

Finally, Catalist notes that Hispanic voters were trending away from Democrats before the 2020 campaign even started. In the midterm elections — when the U.S. electorate as a whole moved sharply toward Democrats — the GOP’s share of the Hispanic vote increased by three points nationally and two points in Nevada.

This seems important. Many prominent accounts of why the GOP gained with Hispanic voters last November have posited 2020-centric explanations: Hispanic workers suffered disproportionately from pandemic-induced shutdowns and feared that Biden would order more of them; the “defund the police” movement alienated conservative Hispanics from center-left politics; Hispanic voters tend to support incumbent presidents, etc.

It is plausible that all of these developments contributed to the drop-off. But none are adequate explanations by themselves, since they cannot account for the decline in Hispanic support for Democrats between 2016 and 2018. Nor, for that matter, can they explain why the Democratic Party’s share of the Hispanic vote in Nevada has declined in every federal election since 2012. In any case, the rightward drift in Hispanic voting patterns doesn’t seem to be a one-off fluke, and Democrats can’t safely assume otherwise.

Taken together, these findings make near-term demographic change look less than ideal for Democrats. In the Rust Belt, generational churn is poised to erode the party’s remaining white working-class support. Already, the erosion of that support has left Wisconsin — the Electoral College’s “tipping point” state in 2020 — about four points more Republican than the nation as a whole.

Meanwhile, if the rightward drift of Hispanic voters continues — an outcome that is far from certain, but which 2020’s results render plausible — then demographic change won’t necessarily paint the Sun Belt blue (or at least not on the Democrats’ preferred timeline). In fact, come 2024, the party may need to invest more energy into defending Nevada than flipping Texas.

Separately, the fact that infrequent nonwhite voters aren’t reliably Democratic indicates that “mobilization” is not an alternative to persuasion. There is no disaffected progressive majority that would assert itself if only voting were easier and the Democratic Party were less preoccupied with appealing to white voters. Rather, such a majority needs to be built through some combination of organizing, policy-making, advocacy, and message discipline.

Finally, if 2020’s demographic trends tell us anything it’s this: Democrats cannot afford for college-educated whites to snap back to their pre-Trump voting patterns. Had professional-class suburbanites not shifted left last year, the party’s declining support among Hispanic and white working-class voters would have been fatal.

If Republicans can win back “Romney-Clinton” voters by nominating garden-variety country-club conservatives, Democrats will be in trouble. Which makes tonight’s gubernatorial election in Virginia a little too interesting.