Joe Biden’s poll numbers aren’t what they used to be. Since last June, approval of the president has fallen by more than ten points, while disapproval has risen by roughly the same amount.

Although Biden has lost ground with most every demographic group, he’s suffered especially steep losses with African American voters. In polling from NBC News, Biden’s approval rating among Black voters has fallen from 83 percent last April to 64 percent today. Quinnipiac University’s surveys show a similar trend, with Biden’s Black support dropping from 78 percent to 57 percent over the course of his first year in office.

Much of that erosion has come in just the last few months. A Pew Research survey released this week finds that Biden has bled seven percentage points of support among Black adults since September. Over that same period, the president lost just four points of support from whites, and virtually none from Asian or Hispanic voters.

For half a century, Black voters have been among the most reliably Democratic constituencies in the country. Thus, the fact that Biden’s rising disapproval has been concentrated within the demographic demands explanation.

Many outlets have attributed the president’s woes to his failure to enact racial-justice legislation in general, and a voting-rights law in particular. As Bloomberg reported last week, “The sudden collapse of voting-rights legislation this week is emerging as the final straw for Black voters with President Joe Biden.” Politico echoed this assessment Thursday morning: “The defeat of the voting-rights bill last week was a final straw for many voters of color disenchanted with the lack of action on that issue as well as on police reform.”

This explanation is intuitive. Civil-rights groups and African American community organizations have made voting-rights and criminal-justice reform focal points of their lobbying on Capitol Hill. Black congressional leaders have made the former a top priority. And there’s little question that voting rights are of special concern to Black voters.

This is especially true in Georgia, the Deep South’s lone blue state and ground zero for Donald Trump’s “Stop the Steal” campaign. In an Atlanta Journal-Constitution poll released Thursday, 24 percent of Georgia voters named “elections/voting” as their most important issue. No other subject was a top priority for quite as many Georgians. And concern about election reform was higher among Black Georgians than among the general population, with 31 percent of the former naming it as their top issue. The same AJC poll found that Biden’s disapproval rating among African Americans in the Peach State had risen from 8 percent in May 2021 to 36 percent today. It’s plausible that Biden’s inability to get voting rights over the finish line is responsible for some part of that great increase.

At the national level, however, there’s reason to suspect that Biden’s defunct democracy agenda is less central to his declining Black support than is commonly presumed.

For one thing, available polling suggests that across America as a whole, the push for voting rights has only limited salience. When Gallup asked U.S. voters to name their nation’s “most important problem” in December, only one percent said “elections” or “election reform.” In a recent poll from the Democratic firm Navigator Research, only 21 percent of Black respondents said that they had “heard a lot” about the Democrats’ main voting-rights proposal, the Freedom to Vote Act. Further, in Quinnipiac’s recent poll, Black voters were actually much less likely than white or Hispanic voters to agree with the statement, “the nation’s democracy is in danger of collapse.”

For another thing, Biden’s erosion of support among Black voters far predates the voting-rights push’s latest failure. In fact, we still don’t have much polling conducted after Democrats failed to come up with the votes necessary to pass the Freedom to Vote Act in defiance of a Republican filibuster this month. Quinnipiac’s survey, which showed Biden’s Black support at a disastrous 57 percent, was largely taken during a period when the president was treating voting rights as his top legislative priority.

There are other explanations for Biden’s difficulties with Black voters that have stronger empirical support. Chief among these is the unpopularity of his vaccine-mandate policy with a small but significant minority of Black Democrats.

Morning Consult’s national tracking poll shows a stark inflection point in Biden’s Black support immediately after the announcement of the mandate. Between September 8 (the day before the mandate’s rollout) and September 20, Biden’s support among Black voters fell by 12 percentage points in the survey. One might write this off as a coincidence, had the pollster not specifically monitored Biden’s standing with unvaccinated Black voters — and found that he had lost 17 points with that segment of the electorate over those two weeks.

As noted above, a post-September decline in Biden’s Black support has been captured in other polls. And there is no analogous inflection point (yet) showing a similar decline in the immediate aftermath of a legislative setback on voting rights.

That Biden’s vaccine mandate would hurt his Black approval more than his failure to deliver on voting rights makes some sense. Generally speaking, presidents are most vulnerable to losing the support of marginal members of their party, which is to say, those who are least firmly attached to their coalition. Marginal Democrats are atypical Democrats, by definition. Relative to strong partisans, marginal Democratic voters tend to hold more heterodox issue positions and to pay less attention to political news. And voters who don’t follow politics closely can quite easily remain unengaged by (if not oblivious to) fights over the details of election law. In most cases, if a pollster classifies you as a “voter,” then you have successfully cast a ballot in a recent election. Which means that, for you personally, disenfranchisement is unlikely to be experienced as a clear and present threat. And in any case, in the time between elections, changes in voting law are unlikely to impinge upon your daily life.

By contrast, vaccine mandates meet low-information voters where they are. If you are a vaccine-averse Black Democrat, Biden’s mandate effectively forced you — or at least, before it was struck down, threatened to force you — to do something you did not want to do in order to keep your job. That is not the kind of policy that is easily ignored. And it is not hard to imagine how a voter with little trust in public authority might revise their political allegiances when their president tries to coerce them into taking a medical treatment they don’t want.

None of this is to say that Biden’s vaccine mandate was not a worthwhile policy on the merits (it was). Nor is it even to assert that the mandate was bad politics; my reading of the polling suggests that they probably gained him about as much goodwill as they cost him. But because Black voters are overwhelmingly concentrated within the Democratic Party — and therefore not politically sorted by their attitudes toward meritocratic expertise, collective responsibility, or trust in government to the same extent that white voters are — a small minority of Black Democrats are vaccine skeptics. And Biden’s mandate appears to have alienated much of this contingent.

Another issue that makes itself felt to Black voters, whether or not they pay attention to goings-on in D.C., is inflation. For months now, polls have indicated that rising prices are a top concern for the electorate as a whole, and that voters overwhelmingly disapprove of Biden’s handling of the matter. Black voters appear to be roughly as concerned about the issue as the general public. In a Morning Consult poll from November, 50 percent of African American voters said that they were “very concerned” about inflation. By contrast, only 37 percent said that they were very concerned about “conflict between political parties.” In the same survey, 54 percent of Black voters said that “the Biden administration’s policies” were responsible for inflation.

African Americans are overrepresented on the lower rungs of our nation’s socioeconomic ladder. And polling indicates that lower-income Americans are more alarmed by inflation than high-income ones. An AP-NORC poll from December found that, among Americans with household incomes of less than $50,000 a year, half say price increases have had “a major impact on their finances,” while only a third of those with household incomes above $50,000 say the same. A Gallup poll released at roughly the same time yielded similar results, with 71 percent of households earning under $40,000 reporting that inflation was causing them severe or moderate hardship, while only 29 percent of households earning more than $100,000 said the same.

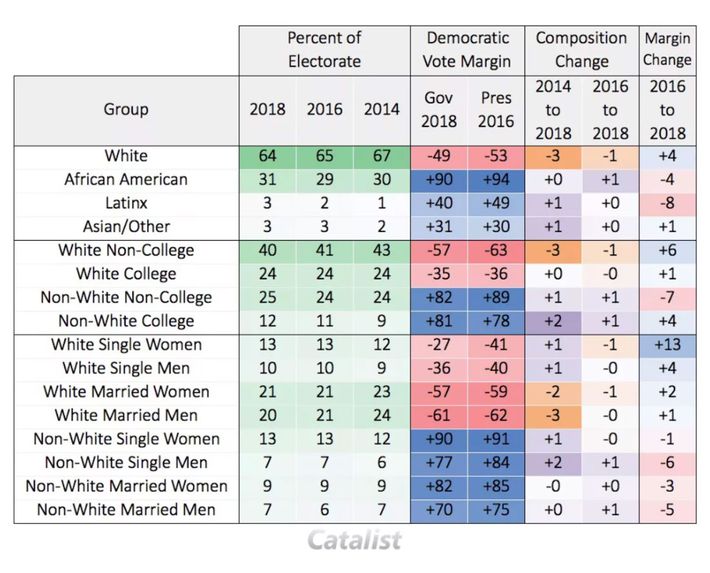

Finally, even before Biden took office, there was reason to believe that Democrats were poised for a gradual, long-term decline in Black support. In 2018 House races, Democrats actually won a smaller share of the African American vote than they had in the 2016 presidential election — even as the party’s overall popular-vote edge in the midterm was five points higher than Hillary Clinton’s two years earlier.

Remarkably, this very slight right turn among Black voters showed up even in Georgia’s gubernatorial race, which pitted the African American minority leader of the state’s House of Representatives, Stacey Abrams, against a secretary of State complicit in voter-suppression efforts. According to the Democratic data firm Catalist, Abrams’s share of the state’s Black vote in 2018 was four percentage points lower than Hillary Clinton’s in 2016.

In 2020, this pattern of very slight Democratic underperformance with Black voters continued, at least in Catalist’s data. Looking at the two-way vote between the Democratic and Republican nominees in each election, Democrats won 97 percent of the Black vote in 2012, 93 percent in 2016, and 90 percent in 2020.

These changes are small enough to dismiss as random variation. But there is a theoretical basis for expecting the Democratic Party’s share of the African American vote to erode over the coming decade. Keeping 90-plus percent of any subgroup united in one partisan camp takes work. The reason Democrats have enjoyed such a landslide margin among Black voters — despite considerable ideological and attitudinal diversity within that demographic — is not that each individual African American Democrat concluded that the GOP was hostile to people like them through their own personal ruminations on current affairs. Rather, as political scientists Ismail K. White and Cheryl N. Laird argue in their book, Steadfast Democrats: How Social Forces Shape Black Political Behavior, the Black bloc vote is a product of “racialized social constraint” — which is to say, the process by which African American communities internally police norms of political behavior through social rewards and penalties. In their account, the exceptional efficacy of such norm enforcement within the Black community reflects the extraordinary degree of Black social cohesion that slavery and segregation fostered.

If this thesis is correct (and White and Laird do much to substantiate it), then it would follow that the erosion of African Americans’ social isolation would weaken racialized social constraint, and thus narrow the Democratic Party’s margin with Black voters. As White and Laird write:

We believe that increased contact with non-blacks and a decline in attendance at black institutions, in favor of more integrated spaces, would threaten the stability of black Democratic partisan loyalty. The result, we believe, would be a slow but steady diversification of black partisanship because leveraging social sanctions for racial group norm compliance would become much more difficult in integrated spaces.

It remains possible that Biden’s failure to deliver legislative breakthroughs on voting rights and police reform have hurt him badly with the Black electorate. In any case, action on both of those issues is morally imperative.

But the widespread sense that the president’s legislative impotence on racial-justice issues is at the heart of his Black voter problem lacks strong empirical support. It seems to derive largely from the analysis of African American politicians, community leaders, and activists. These figures may well represent the views of the typical Black Democrat, but they are generally much more uniformly liberal and politically engaged than the marginal Black Democrat, whose support is most easily lost.

Further, since Black political organizations often find themselves to be the sole advocates for issues that concern African Americans specifically, they are understandably keen to emphasize such issues. Yet it is one thing for an issue to be more important to a minority group than it is to the general public, and another for an issue to be more important to a minority group than other, non-racially-coded issues. It is true that immigration policy tends to be more important to foreign-born Americans than it is to the median voter. But that does not necessarily mean that immigration policy is more important to foreign-born Americans than their wages or cost of living or other matters that tend to be high-salience issues for voters of every stripe. And the same is true of voting rights and African Americans. As the Democratic pollster Brian Stryker recently told the New York Times, “The No. 1 issue for women right now is the economy, and the No. 1 issue for Black voters is the economy, and the No. 1 issue for Latino voters is the economy.” It is possible that Striker’s analysis is mistaken. Either way, only by seeing nonwhite voters as members of minority groups first — and people second — can we assume that their primary concerns depart from those of the public writ large.

None of this is to suggest that Democrats or the press should ignore the political analysis of civil-rights organizations and Black activist groups. These institutions have better insights into the formal obstacles to Black political participation than any polling outfit. And it is quite plausible that such groups will have a harder time mobilizing solidly Democratic African American voters ahead of this year’s midterms if the party fails to deliver on voting rights, criminal-justice reform, or other racial-justice imperatives.

But it is also important to understand where Biden is most vulnerable to Black defections — namely, within the subset of Black voters who strongly identify with neither the Democratic Party nor African American community organizations. How to best retain the sympathies of this ideologically heterogeneous and disorganized contingent is not obvious (other than, say, “simply increase real wages”). But any viable strategy for stanching Biden’s bleeding with such voters will likely begin with the recognition that their priorities and concerns cannot be gleaned from those of highly engaged, ideologically coherent Black Democrats.