Providing all children with a prekindergarten education is one of the best investments a society can make. The minds and personalities of tiny humans are highly malleable. Therefore, the earlier that the public-school system begins cultivating intellectual curiosity, emotional intelligence, and grit in our nation’s youngsters, the more effective it will be at improving students’ later-life outcomes, both in the classroom and outside it. And that isn’t just some Dewey-eyed conjecture. The social-science literature clearly shows that children who attend pre-K perform better academically in later grades, enjoy better health in later life, earn higher incomes, are less likely to get arrested, and are more likely to graduate from high school and complete college.

Or so progressive pseudo–policy wonks like myself used to think.

Unfortunately, a growing body of evidence suggests that we might be wrong. Potentially very wrong. In fact, the most recent — and arguably highest-quality — study of early childhood education in America suggests attending a public pre-K program might make students more likely to struggle academically, skip classes, and misbehave in later grades. And other large-scale, gold-standard studies have produced similar results.

Proponents of universal pre-K shouldn’t dismiss these findings, especially now that Congress is considering implementing a universal pre-K program. But they also shouldn’t forfeit their commitment to the program in light of them. The case for universal early childhood education remains strong, even if the policy is unlikely to fill its backers’ loftiest promises.

Pre-K’s reputation for improving academic outcomes has always rested on shaky ground.

Researchers have been trying to measure the academic and social effects of early childhood education for a long time. But large-scale, high-quality studies are hard to come by. Cities and states generally do not design pre-K programs with an eye toward maximizing their utility as natural experiments. So they typically do not randomly deny some kids access to early childhood education just to provide researchers with a control group. For this reason, among others, many of the studies showing that pre-K has a large impact on later-life outcomes feature very small sample sizes, no pure control group, and/or unusual conditions.

One of the most encouraging and widely cited pieces of research on early childhood education is the Abecedarian Project. Conducted in the 1970s, Abecedarian randomly assigned children from heavily disadvantaged backgrounds to an intensive pre-K program, then tracked their life outcomes, along with those of kids randomly denied access to the initiative. The impact was massive. Kids admitted to the program were five times less likely to be on public assistance as adults, four times more likely to graduate from college, and much less likely to have a criminal record than those who were rejected.

Alas, there are several reasons why the Abecedarian Project is a poor basis for deriving strong conclusions about the likely impact of universal pre-K. A small one is that the experiment’s random assignment of students to the program and control conditions wasn’t 100 percent random. A slightly bigger issue is that its sample size consisted of only about 50 children. But the largest problem, by far, is that Abecedarian did not actually measure the efficacy of prekindergarten, as the term is conventionally understood.

The program didn’t merely provide 3- and 4-year-olds with remedial instruction. Rather, Abecedarian gave its children full-day, year-round care and tutelage from birth through age 5. In early years, every three children enrolled in the program had their own dedicated teacher; as they aged, child-to-teacher ratios never exceeded six to one. Many of the instructors were faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The program provided students with on-site pediatricians, nurses, and physical therapists and helped their families access supportive social services. In today’s dollars, the annual cost per pupil was nearly $20,000.

Were it politically and logistically possible to make this sort of program universal tomorrow, the study’s findings suggest it would be worth the high cost. But no large-scale pre-K program looks much like this. In fact, actually existing public programs differ so extensively from Abecedarian — in terms of teacher-to-student ratio, per-pupil funding, age of onset, and typical faculty qualifications — it’s not clear that the efficacy of the latter tells us much at all about the efficacy of the former.

To be sure, the Abecedarian Project is far from the only study that’s found that early childhood education yields large positive impacts. When Head Start, a federal program that provides early childhood education and social services to low-income children, was first introduced, the very poorest counties in America got access to it, while marginally less impoverished counties did not. A 2005 paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research exploited this discontinuity by tracking the life outcomes of kids in counties with Head Start and comparing them to those of children in nearly identical counties that were just above the income threshold. Its analysis found that low-income kids who had access to Head Start had higher rates of high-school graduation and college attendance later in life.

Meanwhile, a wide variety of relatively small-scale programs that combine prekindergarten with comprehensive social services have shown great promise. In Chicago, the introduction of full-day pre-K classes to disadvantaged neighborhoods was associated with gains in test scores and academic performance through second grade. A recent study of universal pre-K in Boston found enrollees in the program were more likely to graduate from high school. Just this week, a report on Indiana’s pre-K voucher program indicated that low-income students who participated in “On My Way Pre-K” were better prepared for kindergarten than low-income children who did not.

So, there absolutely is evidence that pre-K can make a big difference in kids’ lives. There just isn’t conclusive evidence that it can do so reliably at scale.

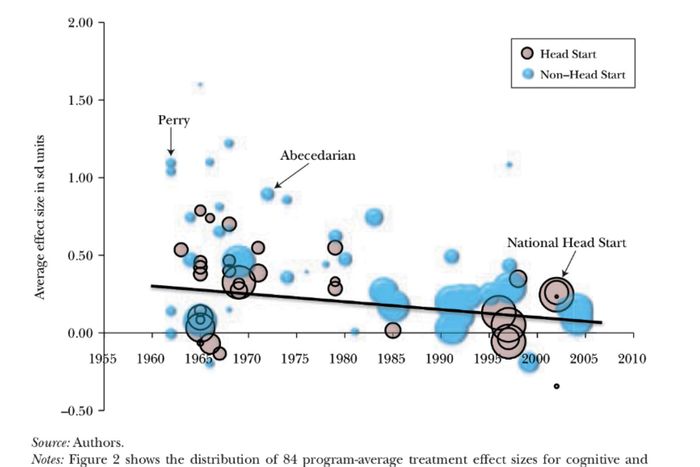

Troublingly, studies that have shown the largest positive impacts of pre-K tend to be based on programs from many decades ago. Over time, there’s been a clear downward trend in the magnitude of positive impacts that researchers have documented, as this somewhat outdated chart illustrates:

The pessimistic interpretation of this trend is that it reflects improvements in research design: As researchers have fine-tuned their studies — concentrating on more realistic proxies for a scalable, universal pre-K program and identifying truly random control groups — the program’s early promise has faded away.

The latest installment of a long-run study of Tennessee’s “Voluntary Pre-K” program lends some credence to that view.

In Tennessee, winning the pre-K lottery seems to have left kids worse off.

Researchers from Vanderbilt University’s Peabody College of Education and Human Development have been tracking the outcomes of participants in Tennessee’s pre-K program for years now. And their study boasts many of the features that have been conspicuously lacking in others on this subject. It’s large scale, tracking nearly 3,000 kids. It features a genuinely random assignment between treatment and control conditions. In some parts of Tennessee, demand for enrolling in the voluntary pre-K program outstripped available spaces, and spots were therefore allocated by random lottery. The researchers took advantage of this, following the trajectories of kids who randomly secured spots and those of kids who didn’t.

Initially, the program appeared to work as its proponents had hoped. In kindergarten, teachers rated the program’s attendees “being better prepared for kindergarten work, as having better behaviors related to learning in the classroom and as having more positive peer relations” than the kids who were locked out of the program. As the children aged, however, this advantage faded — and then reversed.

By the end of kindergarten, the pre-K kids lost their academic and behavioral edge. Once the cohort completed the second grade, the pre-K contingent was scoring lower on academic and behavioral evaluations.

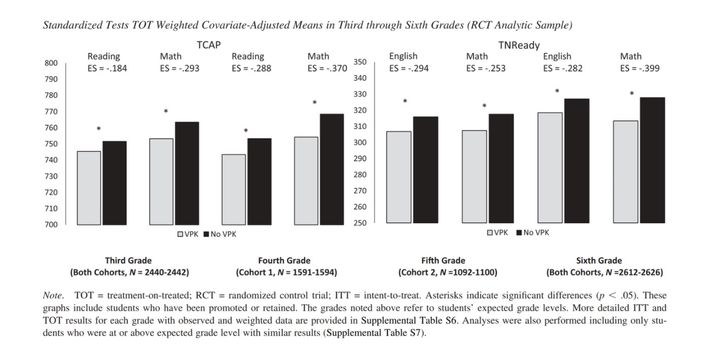

This month, researchers updated their study with results through sixth grade. The negative trend persisted. The students who didn’t attend pre-K continued scoring higher on math and reading than those who did.

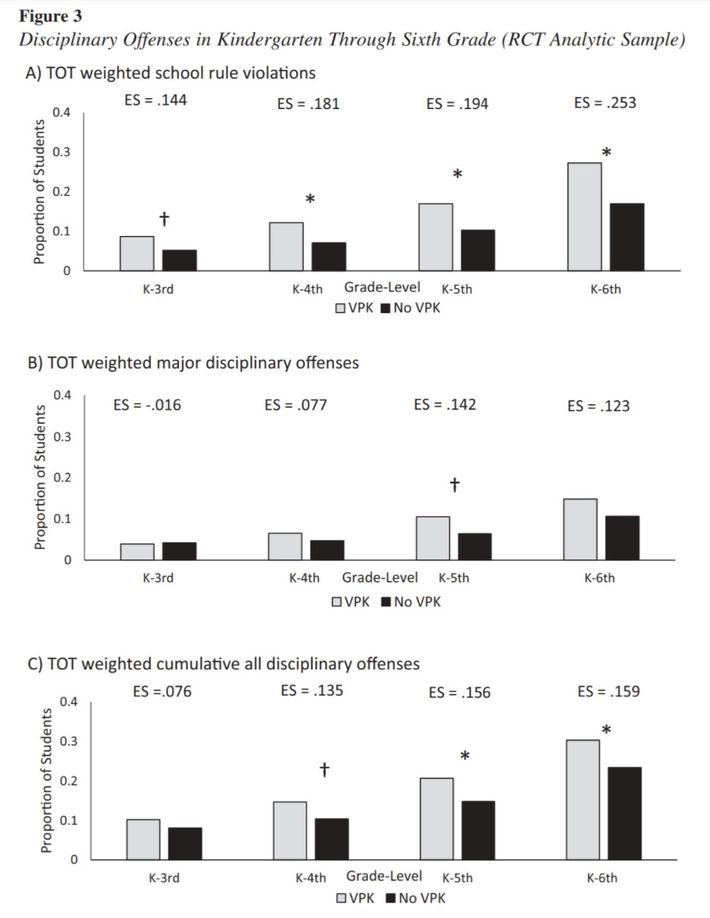

And pre-K attendees were also significantly more likely to miss class and commit disciplinary offenses in school.

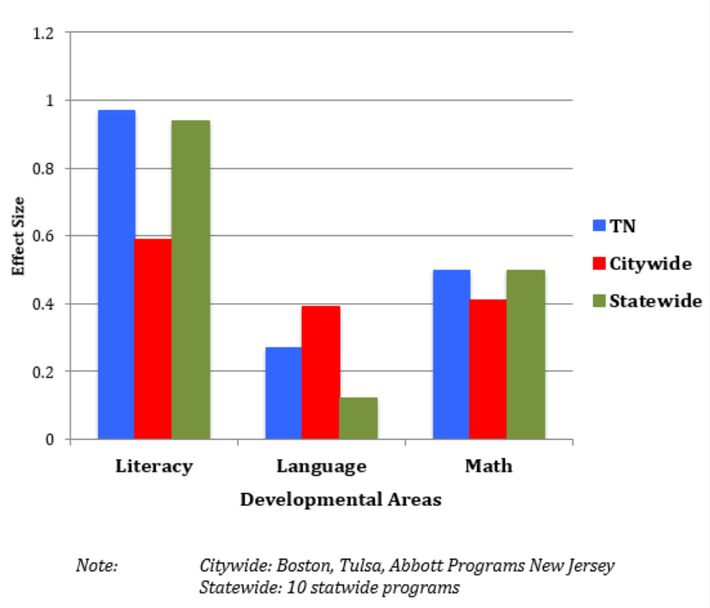

This is not what the researchers expected to find; they’ve admitted that they were “perplexed” when the negative association between pre-K attendance and outcome first appeared. There is no reason to think the study is tainted by any covert ideological motive. Nor is there much basis for dismissing it on the grounds that Tennessee’s pre-K program is unusually low-quality. In terms of the program’s immediate effects — how well it prepared its attendees for kindergarten — Tennessee’s initiative was competitive with other citywide and statewide pre-K programs.

Other standard measures of pre-K quality indicate that the quality of Tennessee’s program was “typical of all pre-K and Head Start classrooms,” according to an analysis from Brookings.

Crucially, the Tennessee study is not a total outlier. One of the only other large-scale, random-control trial studies of pre-K, the 2010 Head Start impact study, also found that pre-K attendees were better prepared than their peers at the start of kindergarten, only to see this advantage all but disappear by the end of first grade.

The research on Tennessee’s program isn’t the first of its kind to show a negative impact on kids who accessed a pre-K-esque program. Although not wholly analogous, a 2015 NBER study of Quebec’s universal-day-care program found that kids who attended public day care reported significantly worse health and life satisfaction and had committed significantly more crimes by their teenage years than their peers in provinces that lacked universal day care.

One aspect of these findings isn’t that difficult to explain. There’s a fairly large amount of data that suggests producing large, lasting gains in academic ability is very difficult to achieve. So, it’s not that surprising that pre-K attendees would revert to the mean, absent any sustained intervention. The fact that pre-K attendance in Tennessee and day-care attendance in Quebec were associated with negative behavioral outcomes is more disconcerting. Those results fly in the face of a lot of both intuition and previous research.

One possible explanation for Tennessee’s results is that kids who were rejected from public pre-K ultimately found more nurturing care from kin, federal pre-K, or the private sector. Among those locked out of the program, 63 percent ended up at home with a parent, relative, or other caretaker, while 34 percent went to private day care or Head Start. It seems plausible that a child who receives one-on-one attention from a family member at preschool age might have more favorable development outcomes than a child in a typical American pre-K program (as opposed to an ideal, Abecedarian-esque one), all else equal.

But that doesn’t necessarily mean that universal pre-K is undesirable. For one thing, the positive results from specific, intensive pre-K programs suggest that the typical American prekindergarten can be substantially improved. But even if it turns out that such programs cannot be scaled up — either because there isn’t political will for the requisite funding or because of some more fundamental constraint — the typical American pre-K (and/or day-care) program still has clear, proven benefits.

Won’t somebody please think of the parents.

Public pre-K programs may not reliably improve enrollees’ long-term academic performance or social behavior. But they do reliably provide parents with a safe, somewhat stimulating place to put their children while they go earn money. And that’s an important service for parents and children alike.

When Washington, D.C., established free and universal preschool, the labor-force participation rate among women with young children in the city rose by 11.4 percentage points over the course of a decade; during the same period, that rate among all American women with young kids inched up by only two points.

That outcome is typical. In other countries, the implementation of universal child care produced similar increases in female workforce participation. What’s more, as Vox’s Kelsey Piper has noted, household economic stability and parental labor-force participation are heavily associated with positive life outcomes for children, including higher rates of high-school graduation and lower rates of incarceration. Thus, if all universal pre-K did was function as a de facto child-care program, there is reason to think it could ultimately improve disadvantaged children’s life outcomes, even if it proves ineffective at increasing their cognitive ability. Simply by enabling their parents to earn higher incomes, the program could improve children’s well-being in the long run. And in any case, it would serve to enhance mothers’ economic autonomy in the immediate term. Which is pretty important, if we want to live in a society in which low-income women are not coerced into abusive relationships for want of economic resources.

All this said, the mixed evidence for pre-K’s efficacy does suggest that if progressives must prioritize some social-welfare policies over others, then they might be wise to favor a child allowance over pre-K. After all, the former increases parents’ economic security instantly and automatically. Further, given that some kids apparently do better under home care than in the typical pre-K program, it might make sense for a universal pre-K policy to include an alternative cash option, which families could use to compensate a relative for providing pre-K-like services if they wish.

On the other hand, in the immediate term, it doesn’t really matter which social-welfare policies progressives wish to prioritize. If the Democratic-controlled Congress does anything to make life easier for parents in America, it will do so at West Virginia senator Joe Manchin’s command. And Manchin, like much of the U.S. electorate, would rather give parents universal pre-K than unconditional cash assistance, owing to the mistaken belief that the latter would enable idleness or drug abuse.

Pre-K may not be the panacea that some of its boosters make it out to be. But it is nevertheless the only de facto public child-care program that has some bipartisan support within the U.S. That makes the young institution worth nurturing in the hope that it eventually outgrows its present flaws.