Joe Biden is America’s least hawkish president in decades. During his first year in office, Biden ended the U.S. war in Afghanistan despite media pressure to sustain it and dramatically scaled back America’s drone war. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine this February, Biden rejected proposals to establish a no-fly zone over Ukraine and ruled out any other form of direct NATO intervention in the conflict. Indeed, his administration has been so wary of a direct confrontation with Russia that it has sought to quash efforts to transfer fighter planes to the Ukrainian military.

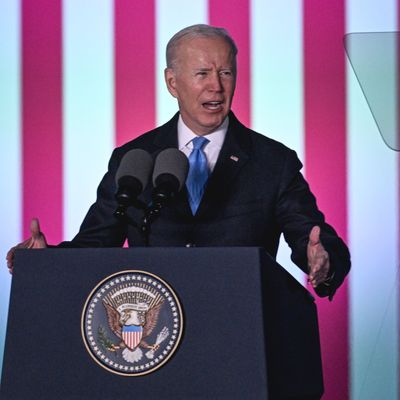

But Biden is also a 79-year-old man with penchant for appending his scripted speeches with folksy asides and a long history of saying stupid and/or impolitic things. Thus the president chose to punctuate his speech about Russia in Poland on Saturday with the ad-libbed declaration: “For God’s sake, this man” — meaning Vladimir Putin — “cannot remain in power.”

This was, by all appearances, a straightforward call for regime change in Russia. Which is a pretty crazy thing for any U.S. president to endorse, let alone one who has spent weeks emphasizing his concern for averting “World War III.” According to the U.S. military’s own assessments, Putin “would probably use a nuclear weapon if he concludes that his regime is threatened.” So announcing that Putin’s regime cannot remain in power — for no higher purpose than courting applause — was imprudent on Biden’s part.

The White House was quick to clarify that Biden knows not what he says. U.S. officials explained that the president merely meant that Putin cannot be allowed to retain power “over his neighbors or the region.” The administration let it be known that Biden’s closing line was unscripted and that U.S. policy had not changed.

Nevertheless, many diplomats fear that Biden’s words will make it more difficult for the West to broker peace between Russia and Ukraine. French president Emmanuel Macron said of Biden’s remarks, “I wouldn’t use those terms, because I continue to speak to President Putin, because what do we want to do collectively? We want to stop the war that Russia launched in Ukraine, without waging war and without escalation.”

Fortunately, Russia’s response to Biden’s ad-lib has been muted thus far. In fact, Russian state media has if anything played down the president’s extemporaneous call for regime change, perhaps because America’s determination to overthrow Putin was already a well-established fact within the world presented by Kremlin propaganda.

For his part, Putin had no illusions that the West welcomed his rule. Even before Saturday’s speech, Biden had referred to his Russian counterpart as a “butcher” and a “war criminal.” It seems unlikely that the president’s latest indiscretion will radically change Putin’s geostrategic calculus. Russia had good reason to avoid instigating a direct conflict with NATO before Biden’s speech, and he still does in its aftermath.

Ultimately, Biden’s words are of less consequence than his intentions. The pressing question is whether the former accidentally divulged the latter.

As Michael Hanlon of the Brookings Institution told the Washington Post, Biden’s comments suggest that his “top team is not thinking about plausible war termination. If they were, Biden’s head wouldn’t be in a place where he’s saying, ‘Putin must go.’ The only way to get to war termination is to negotiate with this guy.”

In the Financial Times, Edward Luce argues that Biden’s gaffe betrayed an inconvenient truth — namely, that “it is hard to picture the circumstances in which the US would reincorporate Russia into the global economy while Putin is still there.”

In Luce’s account, the bipartisan nature of anti-Russian fervor in the United States post-2016 would make it “politically excruciating” for Biden to lift sanctions on Russia in the absence of regime change in Moscow. Even if Putin’s ouster is not America’s official stance on the conflict, it is our effective one. And this maximalist position threatens to drive a wedge between the U.S. and its European allies, which are more eager to normalize relations with Moscow due to their greater economic dependence on Russian exports.

To my eyes, Luce’s account looks a bit alarmist. He writes that the Biden administration has taken pains “to avoid saying when or even whether US sanctions on Russia could be lifted,” and he suggests that this reflects its tacit commitment to waging an indefinite economic war on Russia. But the White House has given a few indications that this is not the case.

U.S. Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs Victoria Nuland said earlier this month that the U.S. will lift its sanctions if Putin “ends this war, and helps rebuild Ukraine and reestablishes peace and recognizes that country’s sovereignty and territorial integrity and right to exist.” More recently, Secretary of State Antony Blinken said that U.S. sanctions against Russia are “not designed to be permanent” and would go away if Russia committed to an “irreversible” withdrawal of its troops from Ukraine. It is not clear what would qualify as an “irreversible” withdrawal. If Russia agrees to a peace agreement that includes western security guarantees for Ukraine — which is to say, pledges that compel western nations to defend Ukraine against a future Russian invasion — however, that would seem to fit the bill.

More significant than any of these words is the White House’s efforts to retain unilateral authority over U.S. sanctions against Russia. At present, America’s most devastating economic measures are rooted in executive authority, not legislative mandate. And Biden has sought to keep it that way: The administration only embraced a ban on Russian energy imports to the U.S. after it became clear that such an embargo had traction in Congress. As Bloomberg reported, the White House specifically sought to cut off the legislative push for an import ban so as to retain “more flexibility to adjust import controls later if tensions ease.”

The notion that it would be politically excruciating for Biden to lift sanctions on Russia should it reach a peace deal with Ukraine, but retain Putin as its leader, also seems questionable. President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has already demonstrated a gift for pressuring western leaders to aid Ukraine’s cause, even in ways that would not guarantee Ukraine’s survival yet would impose economic costs on western consumers. If Ukraine and Russia reach a peace deal contingent on America’s agreement to lift sanctions on Russia, then Zelenskyy could once again plead his case to the American public and Congress. And in that happy hypothetical, Zelenskyy would be asking the U.S. to embrace a policy that would immediately bring peace to Ukraine and lower prices for American consumers while increasing profits for American corporations. Given Biden’s manifest concern with reducing inflation — and U.S. voters’ greater concern with price stability than Russian aggression — I don’t see why lifting sanctions would be a very hard ask in that scenario.

All this said, it is absolutely true that Biden’s precise conditions for sanctions relief remain murky. And the White House has declined to say whether it has empowered Zelenskyy to offer sanctions relief in his negotiations with Russia. The U.S. should give the Ukrainian president that authority. Our government’s position should be that any peace deal that’s good enough for Kyiv will be good enough for Washington.

If Biden doesn’t want Russia to think the endgame of his sanctions is regime change in Moscow, his administration should say — in clear, concrete terms — what that endgame actually is.