There is one name that comes up frequently in court in the Larry Ray trial, but that name is never given any context. That’s because of what happened to Iban Goicoechea.

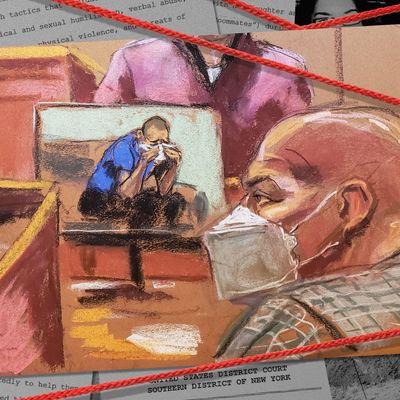

Ray is a 62-year-old Brooklyn native accused of manipulating, abusing, and sex-trafficking his daughter’s former friends and roommates at Sarah Lawrence College. He has pleaded not guilty to all charges and his trial, taking place in federal court in lower Manhattan, is expected to conclude next week. The testimony from those young people in court has been horrific: They are telling a coherent story of years of beatings, cruelty, forced sex, and forced labor.

The question people often ask is: How could Ray accomplish this control? And the answer is that he did much of this with narrative.

One person testified that she thought of Ray as an action-movie character — a good and important man who was screwed over by powerful men after trying to do the right thing.

Ray’s mythology has two foundational elements: his victimhood as someone who is regularly poisoned, hunted, and betrayed, and his legendary background as a man connected to military and police.

In particular, he used war stories and military posturing to enchant, and then paralyze, the people around them. But what from these stories was even real?

He portrayed himself as a former Marine, when his actual military service amounted to 19 days in the Air Force in 1981. In court this week, prosecutors let slip that Ray was dishonorably discharged. And, if his defense wanted to use details from this period, the government said, it would have no choice but to set the record straight with “a whole lot of other very damaging information about Mr. Ray’s purported military career.”

And Ray’s “purported military career” surely influenced Iban Goicoechea most of all.

Goicoechea met Ray because he dated Ray’s daughter, Talia, in high school. Ray quickly became a mentor. After Goicoechea dropped out of college, Ray urged him to join the Marine Corps. Goicoechea enlisted in 2006 and was deployed in Iraq and Afghanistan. He saw extensive combat and witnessed friends die in service.

When he returned home, Goicoechea suffered from post-traumatic-stress disorder, a diagnosis he was open about. He enrolled at Columbia University, where he helped conduct studies on PTSD in combat veterans. “While veterans may have the benefit of returning to a ‘Sea of Good Will,’ many times we’re left without a paddle or bearing, and in dire need of both,” he wrote on a now-defunct website called Veterhands.

Both of Goicoechea’s parents died not long after he returned home. In the Veterhands post, he wrote that he “decided to take a year to address personal issues, and was fortunate enough to have a mentor to help me through processing those issues.” That mentor was Ray.

As he did with the other alleged victims in this case, Ray employed bizarre, often violent methods with Goicoechea, who regularly overnighted in Ray’s Upper East Side apartment.

Santos Rosario, the second victim to testify in the trial, described Ray punching Goicoechea. Rosario also said he saw an incident in which Ray woke Goicoechea up from a nap by holding a spatula to his chest, telling him it was “time to die.” He told Goicoechea that he had to choose between his own life and his father’s. Then he slapped him in the chest with the spatula and said, “Let’s make some eggs.”

Still, Goicoechea was a faithful servant. Many people told us that Goicoechea, who had served as the driver in his company commander’s personal-security detail, now served as Ray’s personal chauffeur. Ray would sometimes make Goicoechea wait in the car for hours while he had dinner with friends. Another time, Ray rented a U-Haul in Goicoechea’s name and kept it so far beyond its due date that the vehicle was declared stolen. Eventually, two NYPD officers found the vehicle with Goicoechea in the driver’s seat. The cops approached with guns drawn and arrested him. He spent the night in jail. Online, Goicoechea wrote that his experiences with Ray provided him with “immense growth.”

At Columbia, Goicoechea bonded with fellow veterans. Eric Hines, an Army intelligence veteran, said Goicoechea was the type of person who would always put himself last, “who would see your need for a shirt before you did yourself, remove his and insist that you take it.”

Hines remembers meeting Ray outside the university. “Iban really liked to introduce him to people because he thought so highly of him,” Hines said. “But I think Larry kept his distance from us. He was smart and manipulative enough to know if he said any of the shit that he said around me or my peers, we would have said that he was full of shit.”

In 2019, shortly before the publication of our original article about Ray, Goicoechea gave us an interview. He described his unalloyed belief in Ray’s stories. Yes, people had poisoned Ray and his loved ones, including Goicoechea, at the behest of “this underbelly of organized crime where people benefit from injuring others and disrupting their lives,” he said.

At the end of our interview, Goicoechea said that he was currently hospitalized with symptoms of osteoporosis, which he blamed on poisoning. (Goicoechea also recorded our interview and sent a copy of it to Ray.)

In fact, he was at a Veterans Affairs hospital in the Hudson Valley receiving treatment for PTSD, according to John Williams, one of his closest friends from the Marines.

In 2015, Goicoechea had moved out to stay with Williams and his wife in Oregon. “He definitely seemed like he was missing his purpose,” Williams said. “Sitting around, waiting to be told what to do.”

Williams attributes this state of mind to Larry’s influence. “It just seemed like that he more or less took him in a fairly fragile state after getting out of the Marine Corps, and with both of his parents dying, and then just made it so he had no ability to make decisions for himself,” he said.

Ray’s missions continued after our article was published. At Ray’s direction, he posted a long message in our story’s comments section defending his mentor. The story’s sources, Goicoechea wrote, were the same people who “were deliberately antagonistic towards myself, others, and the group as a functional whole, factually poisoned, and deliberately attempted to destroy the life of Lawrence Ray, his daughter Talia, and those amicably associated with them.”

After leaving the New York hospital in 2019, Goicoechea went back to Oregon to crash with Williams. But in 2020, Williams and his wife took Goicoechea to a VA hospital, concerned by his increasingly erratic and paranoid behavior. Williams doubts his friend ever got the help he truly needed.

“There’s a lot of different treatments and things that work decently for PTSD. But deprogramming somebody from a cult is a completely different freaking ballgame,” he said. “I think that’s why he never really got better, despite having been inpatient a bunch of times. It’s because they weren’t attacking the right angle. And it’s because he was still in that mind frame of believing Larry.”

Shortly after Ray’s arrest in February, 2020, Goicoechea left the hospital against medical advice. After he left, Williams — to whom Goicoechea had granted power of attorney — asked the hospital who Goicoechea had been in contact with while he was staying there. The only names on the list were himself, his wife, and “Uncle Larry.”

Soon after, Williams heard from Special Agent Kelly Maguire, the lead FBI agent investigating Ray. She wanted his help tracking down Goicoechea in order to ask him about Ray. That worried Williams. “I was like, ‘I don’t know what he’s going to do,’” he said. “Because he was so far in that headspace and believing everything Larry said, and because the FBI wanted to talk to him, it probably made him even more paranoid.”

Ray often told his followers that he was working to save them from killing themselves, even as his actions drove them toward despair. In a 2019 interview with us, Ray estimated that there had been 12 suicide attempts among the students living with him. He seemed almost proud of this fact — as if it justified his extreme and violent interventions in their lives. Although Ray didn’t mention Goicoechea at the time, the topic of suicide clearly loomed in the veteran’s mind. “Too many of the Marines I’ve fought beside were killed in action, and too many took their own lives after returning home,” Goicoechea wrote.

In early March of 2020, in a small town in Oregon, Goicoechea died by suicide.

Before Ray’s trial began, the judge ruled to exclude any information about Goicoechea’s death from the trial, agreeing there was no evidence linking Ray to the veteran’s death. Jurors likely won’t learn about his story until after they deliver a verdict.

“I don’t think Iban’s suicide was because of Larry. He died in Afghanistan. His assurance that he was fine when he was clearly not, in my opinion, is what led to Iban’s death,” said Hines. “But Larry took advantage of Iban’s service. People with severe PTSD can sometimes experience paranoid ideation. Paranoid people are easy to manipulate. Getting people to do stuff by making them feel like they’re doing something, like part of Larry’s bullshit spy network, can make them feel like they’re part of this higher cause. They really want meaning in life in the context of service. That is an incredibly powerful tool.”

“We hope to see him laid finally to rest in Arlington,” Hines said, “where he deserves to be. Larry deserves to be in prison.”

“Personally, I fully blame Larry for his suicide,” Williams said. In the last few years of his life, Goicoechea “seemed like a complete hollow shell of a person, and I think it was from the fucked up things Larry did to him.”

But Williams remembers him in other ways, too, as his charming, fun-loving buddy who played with the puppies on their base in Iraq and took dive lessons in Mexico so he could explore aquatic ruins. “He wanted to be an underwater archaeologist, that was his thing,” Williams said. “If he had just not been back involved with Larry at all, I think he would have probably succeeded at that.”